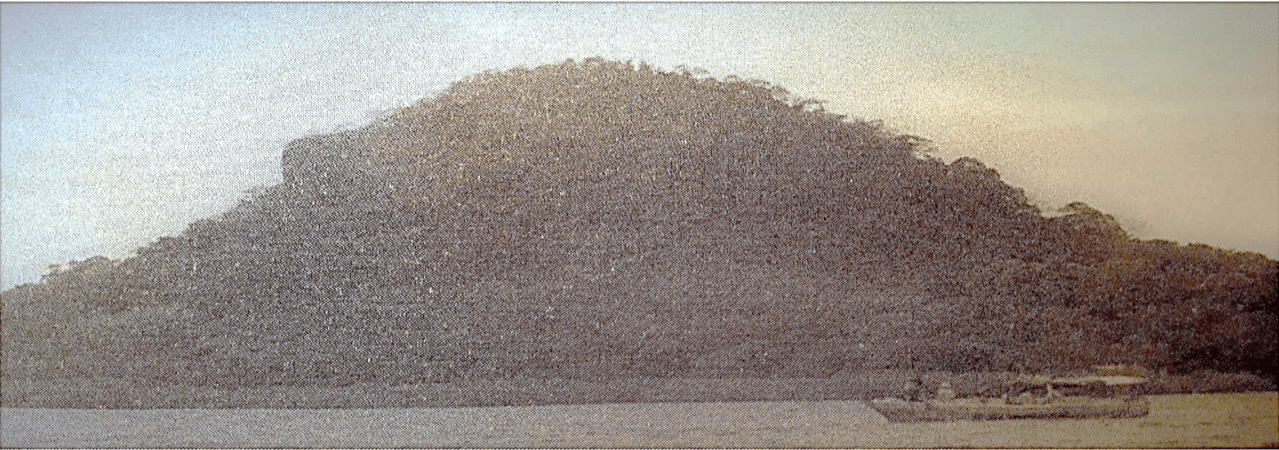

Cerro Rogatu (topónimo en ngäbere) o Pan de Azúcar (topónimo en español) desde el cual Gö Caballero se arrojó al Océano Pacífico

Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011:77 | Rogatu (toponym in ngäbere) or Pan de Azúcar (toponym in Spanish) hill from which Gö Caballero threw himself to the Pacific Ocean

Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011:77.

Prólogo

PRÓLOGO

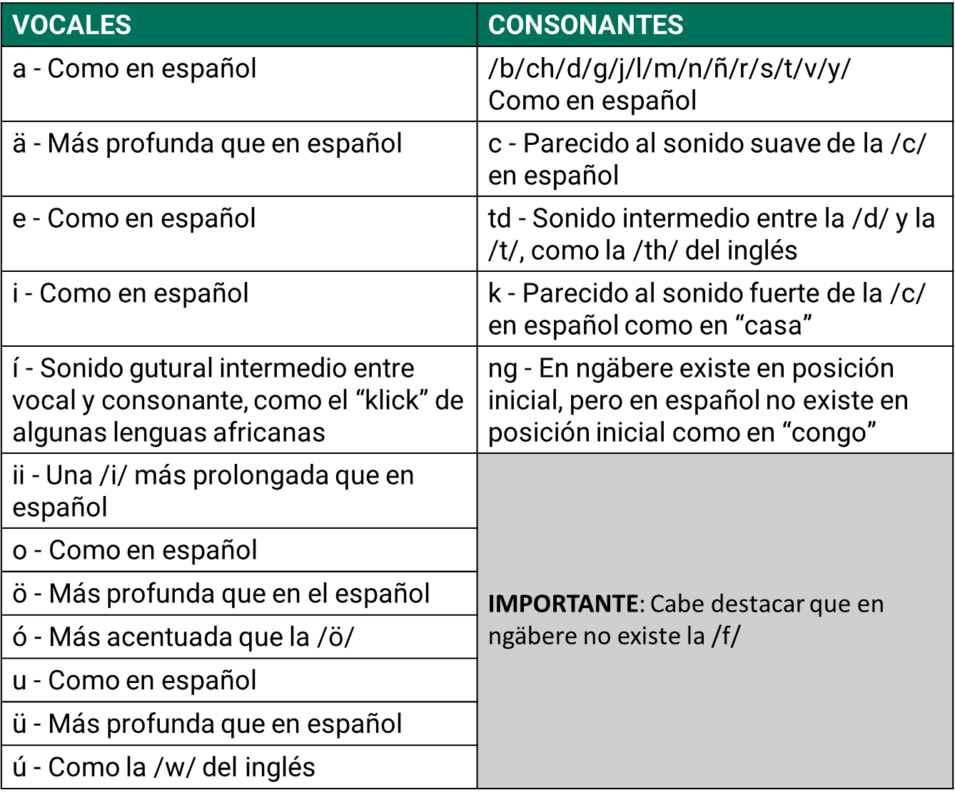

Para facilitar la lectura en ngäbere, hemos adaptado, con algunas modificaciones, el sistema en el breve diccionario ngäbere-español Kukwe Ngäbere de Melquiades Arosemena y Luciano Javilla, publicado en 1979 por la Dirección del Patrimonio Histórico del Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INAC), ahora Ministerio de Cultura, y el Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

También conviene aclarar que esta historia proviene de narradores residentes en el corregimiento de Potrero de Caña, antes distrito de Tole de la provincia de Chiriquí, ahora distrito de Müna de la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé, de donde es oriundo el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, el recopilador-escritor. Por consiguiente, la fonología corresponde a la variación dialectal o regional “Guaymí del Interior” (vertiente del Pacífico) y que difiere del “Guaymí de la Costa” (vertiente caribeña de la provincia de Bocas del Toro y del ahora distrito de Kusapin en la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) en la Gramática Guaymí de Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, publicada en 1980 por Fe y Alegría. Esta variante corresponde a la que Arosemena y Javilla denominan “Chiriquí” y que contrasta con las variantes caribeñas de Bocas del Toro y costa de Bocas.

Esta etnohistoria fue publicada en 1986 en Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere/Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Etnohistoria Guaymí), por la Asociación Panameña de Antropología, con el Convenio PN-079 de la Fundación Inter-Americana (FIA) gestionada por el Dr. Mac Chapin, Antropólogo, quien nos animó a que siguiéramos el ejemplo que él había sentado al recopilar el Pab-Igala: Historias de la Tradición Kuna, publicadas en 1970 por el Centro de Investigaciones Antropológicas de la Universidad de Panamá, bajo la dirección de la Dra. Reina Torres de Araúz.

Este libro representó la labor del Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, cuando era estudiante en su segundo año en el Centro de Enseñanza e Investigación Agropecuaria de Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad de Panamá (FCAUP), no solo de escribir en ngäbere las narraciones que había oído relatar a sus familiares en su comunidad, sino también su esfuerzo de traducirlas al español como persona bilingüe que es, al igual que otros indígenas en Panamá quienes se esfuerzan por recibir una educación formal.

Las etnohistorias fueron recopiladas, grabadas en casetes y escritas por el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo en 1983 y 1984.

Como Profesora-Investigadora de Antropología y Sociología Rural en el CEIACHI de la FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Antropóloga, Ph.D., animó a Roger, como uno de sus estudiantes, a escribir las historias, convencerlo y demostrarle que no explotaría ni abusaría de su trabajo, sino que se le reconocería su mérito. Por consiguiente, la antropóloga se limitó solamente a hacer algunas correcciones de forma y estilo en las traducciones al español sin alterar su contenido.

Animamos a estudiantes de los siete pueblos originarios en la República de Panamá, y a docentes en escuelas, colegios y universidades públicas y privadas en Panamá, a que escriban en sus propios lenguajes y traduzcan al español las etnohistorias y cantos que escuchan en sus familias y comunidades, como parte de su educación informal.

También animamos a lectores de estas etnohistorias en ngäbere, español e inglés, a que dibujen las escenas que más les gustaron, como hicieron en el 2002, estudiantes en un curso de Educación y Sociedad, orientado por la Dra. Joly, en la Facultad de Educación, Universidad Autónoma de Chiriquí.

Artículo 13 de la Declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas, aprobada por la Asamblea General, en su 107ª sesión plenaria el 13 de septiembre de 2007:

- Los pueblos indígenas tienen derecho a revitalizar, utilizar, fomentar y transmitir a las generaciones futuras sus historias, idiomas, tradiciones orales, filosofías, sistemas de escritura y literaturas, y a atribuir nombres a sus comunidades, lugares y personas, así como a mantenerlas.

- Los Estados adoptaran medidas eficaces para asegurar la protección de ese derecho y también para asegurar que los pueblos indígenas puedan entender y hacerse entender en las actuaciones políticas, jurídicas y administrativas, proporcionando para ello, cuando sea necesario, servicios de interpretación u otros medios adecuados.

ROGARA METO O GÖ CABALLERO

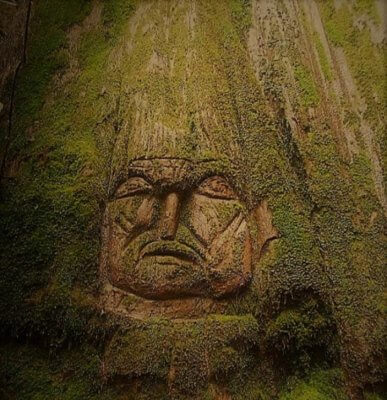

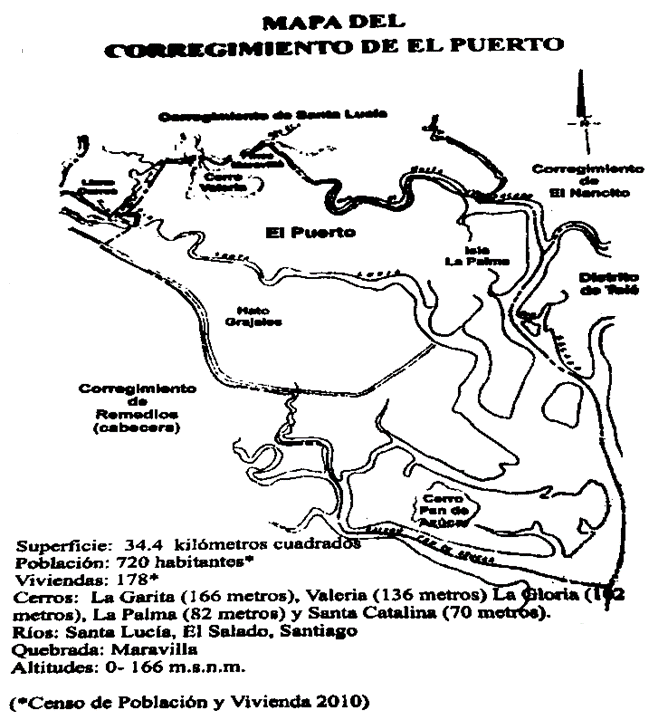

Este personaje era un suguiá quien vivía por la cordillera entre los distritos de Tolé (ahora distrito de Muna de la Comarca Ngäbe Bugle) y Remedios.

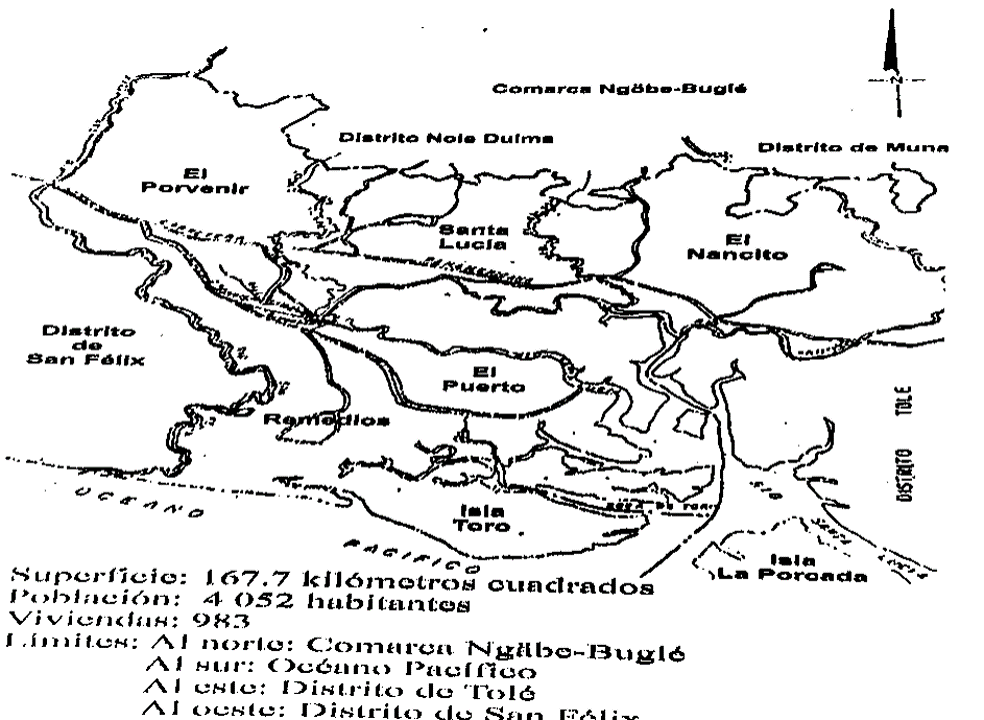

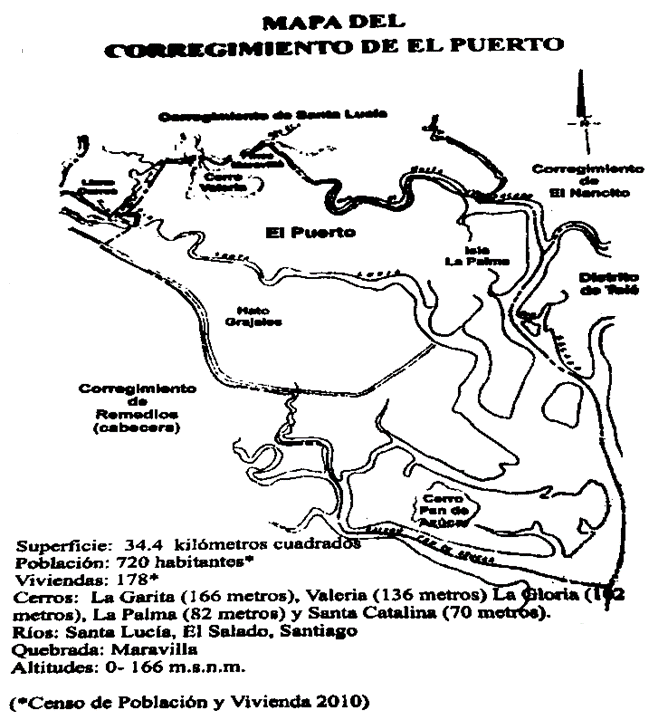

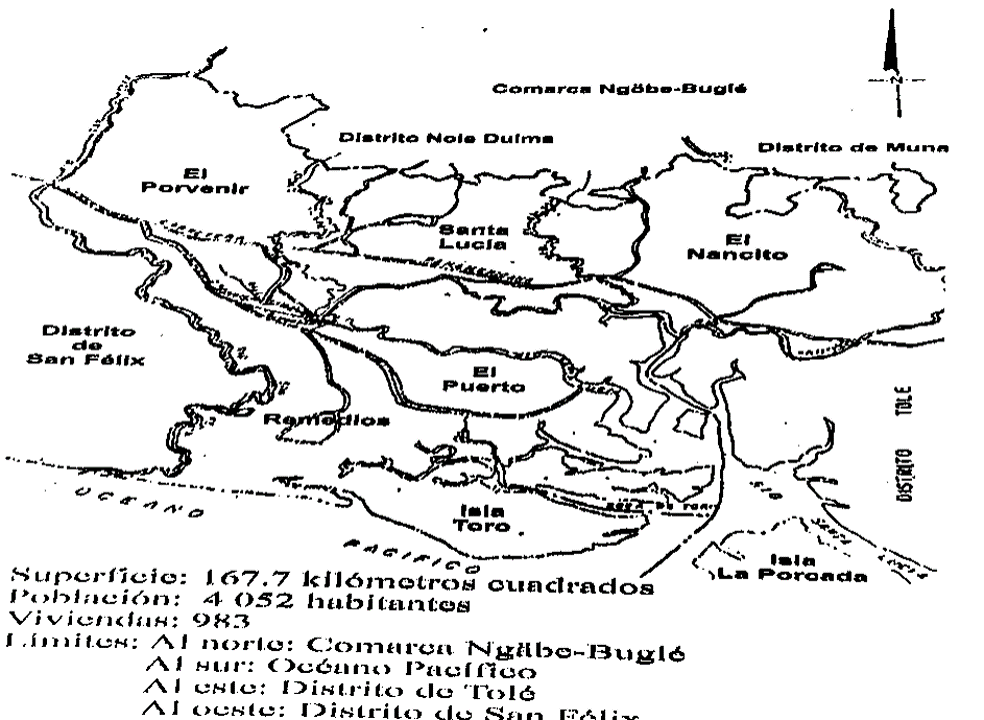

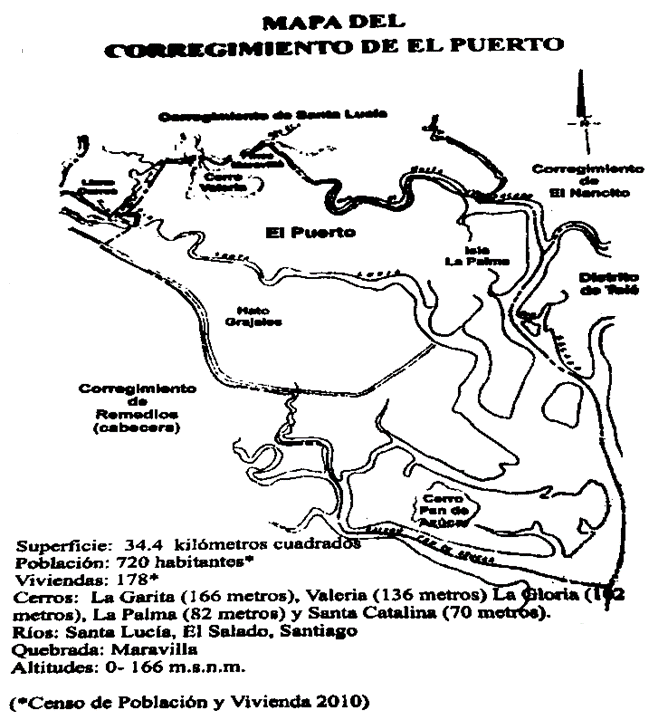

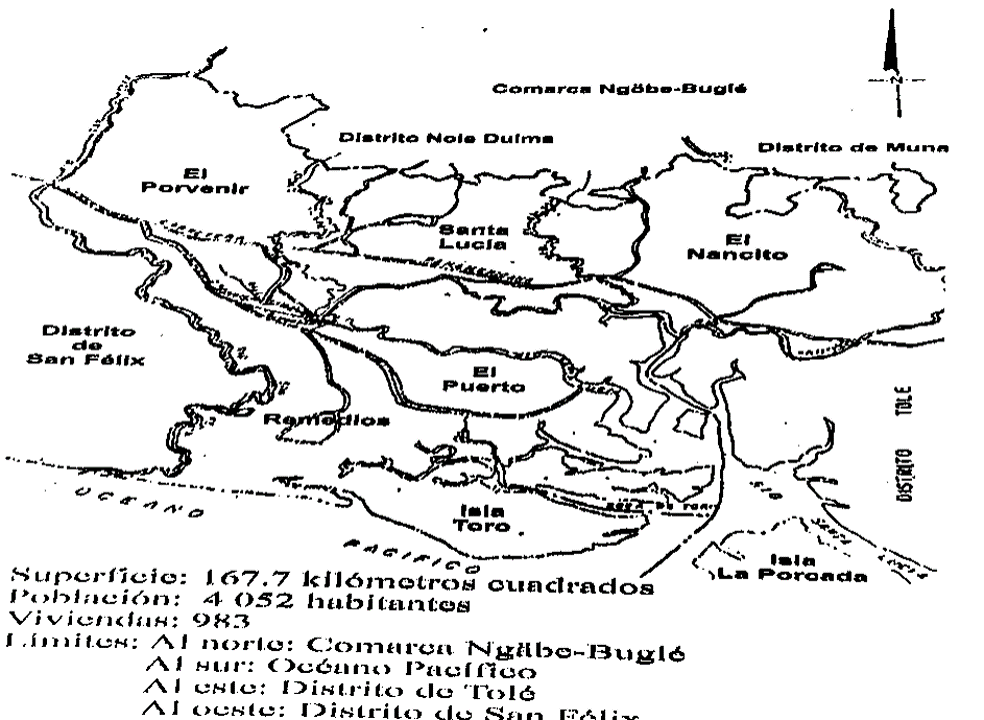

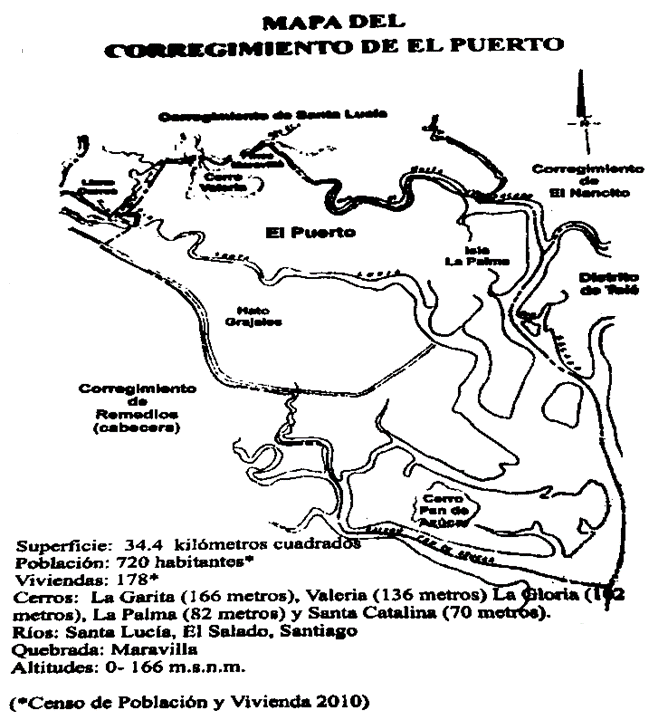

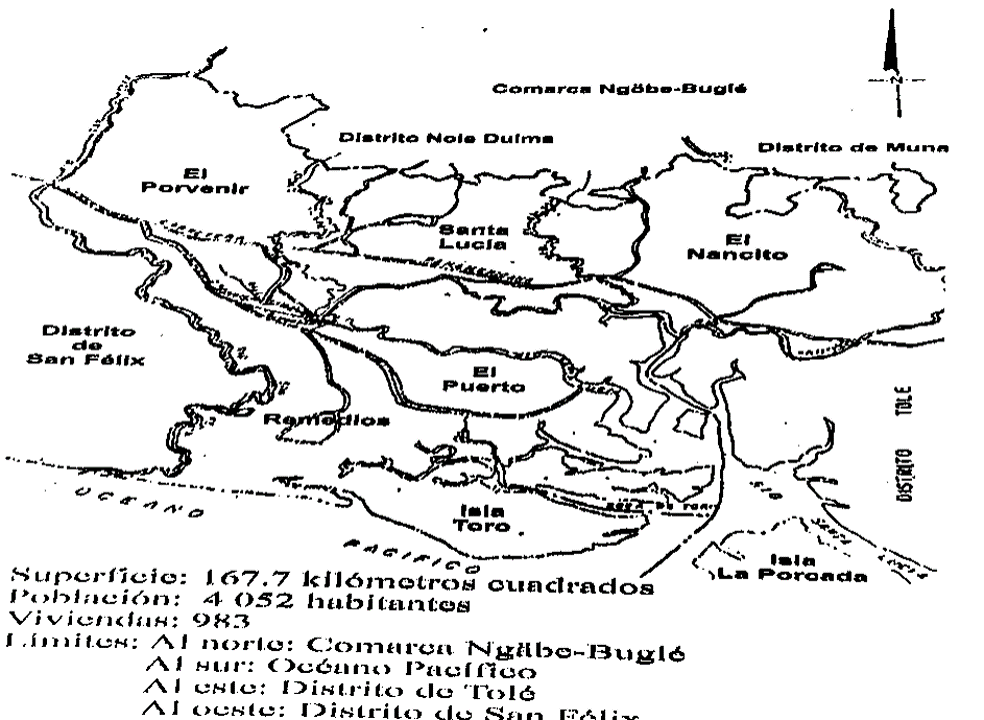

En el lado izquierdo del mapa del distrito de Remedios está el río San Félix que divide el distrito de San Félix del distrito de Remedios. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros Olimpia Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2011:34 | On the left side of the map of the district of Remedios is the river San Felix that divides de district of San Félix from the district of Remedios. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros Olimpia Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2011:34.

Tenía una característica muy particular, por la cual casi todos los indígenas que habitaban por los mencionados lugares lo conocían. Se dice que se volvía en dos personas o, bien, podía estar en dos lugares distintos al mismo tiempo.

En los tiempos de la colonización y hasta hace pocos días, los suguiás eran perseguidos por los colonos, luego por sus descendientes, porque, según ellos, éstos eran brujos quienes los atacaban en sus expediciones, malograban sus proyectos, producían fracasos y no los dejaban andar tranquilos. Y cualquiera otro fenómeno que les ocurría, como desconocían sus procedencias y la razón de las mismas, entonces se los cargaban a los suguiás, considerándolos como brujos. Incluso, en la actualidad, se les llega a considerar lo mismo por los elementos no-indígenas.

Esto motivó a que los colonos, los criollos y sus descendientes mantuvieran una ardua campaña por liquidar a todos los suguiás quienes estuviesen viviendo en la región Guaymí (Ngäbe). Realizaban viajes constantes en la cordillera en busca de los suguiás, haciendo encuestas, entrevistando a los indígenas para que les dieran la información sobre la existencia de suguiás, para ir a buscarlos y llevarlos a la ciudad, para luego encarcelarlos o bien matarlos, con la intención de ir eliminando paulatinamente a todos los suguiás (brujos), para evitar fenómenos desagradables y negativos en sus empeños por adueñarse de las tierras y recursos naturales indígenas.

Los Guaymíes (Ngäbe), en su afán de salvaguardar la integridad física de los suguiás, muy poco o nada decían a los investigadores. Por ese motivo los enemigos y los elementos extraños, no-indígenas, muy poco conocían de suguiás. Y aún en la actualidad, muy poco se habla de suguiás, nada hay escrito sobre ellos y, si existe, no se han revelado a los elementos ajenos a los indígenas para mantenerlo oculto.

Así que, en esas circunstancias le tocó vivir a Gö Caballero, confrontando la inclemencia de los tiempos. Parece que, en busca de los suguiás, se encontraron con Gö y lo tomaron preso, llevándolo al cuartel de Remedios donde iba a pagar la pena de su brujería. Pero, el notable Rogara Meto o Gö Caballero, ni siquiera tomó importancia a la misma y sólo se limitó a seguir a los guardias para la cárcel.

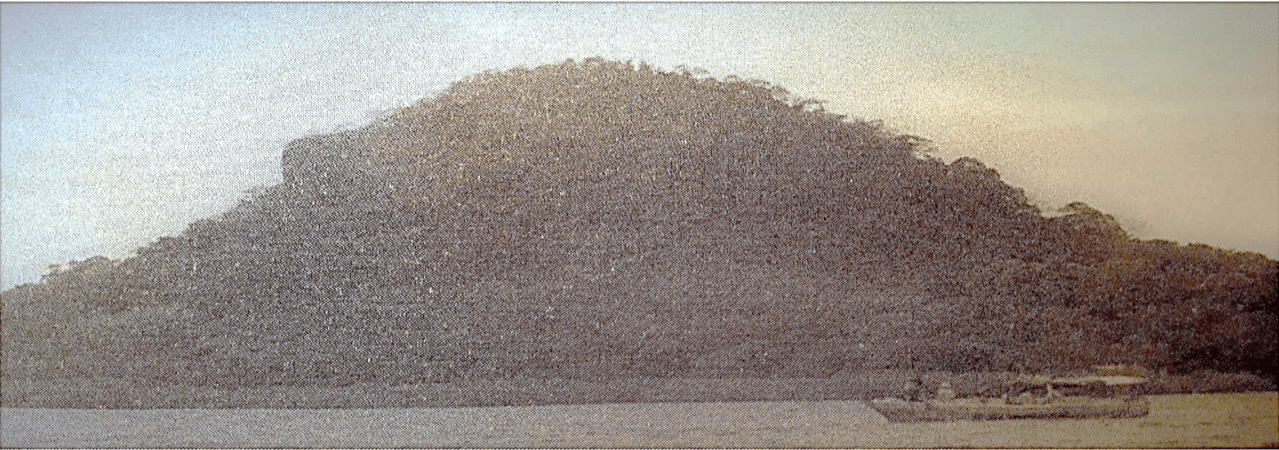

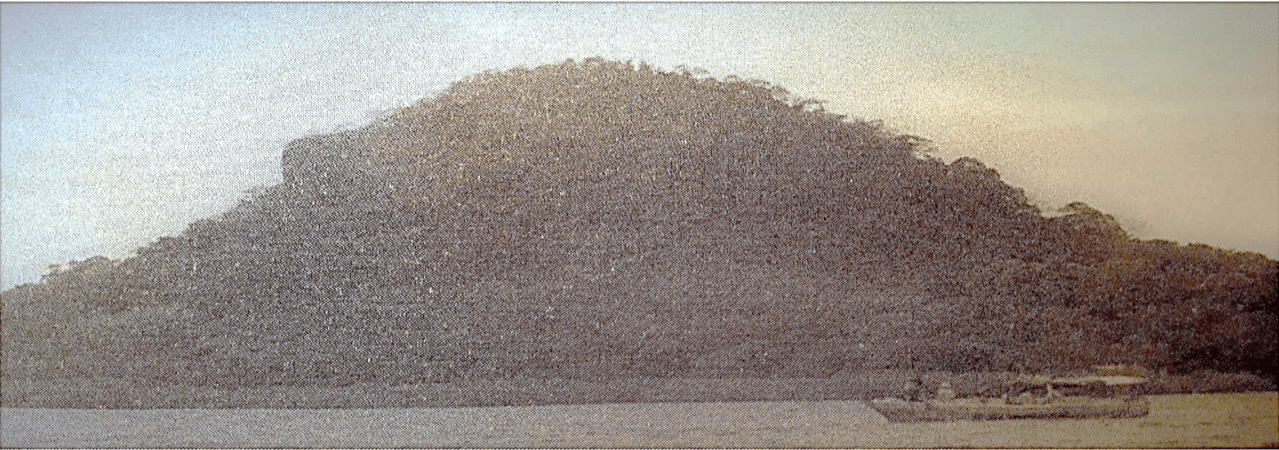

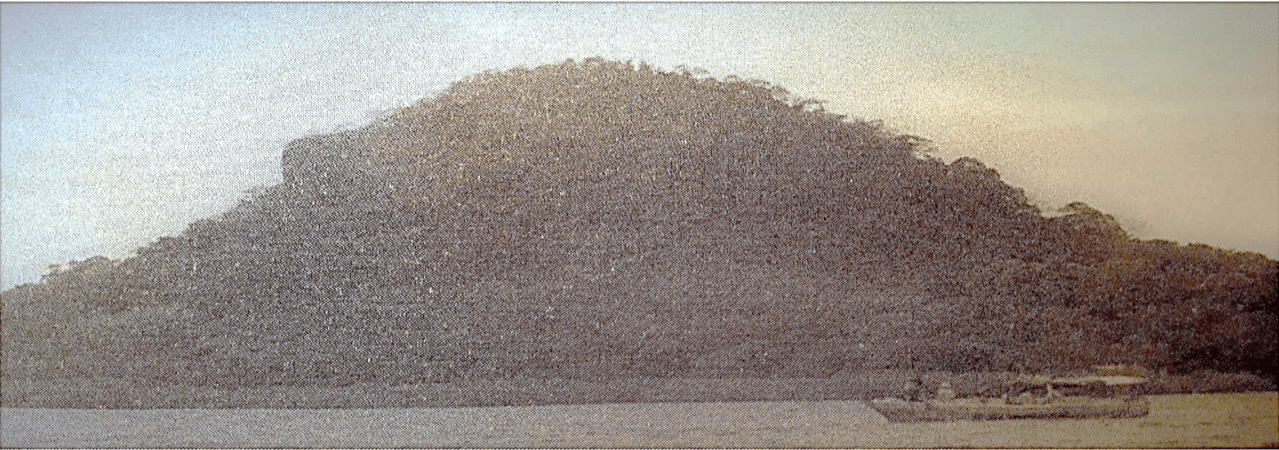

Cerro Rogatu (topónimo en ngäbere) o Pan de Azúcar (topónimo en español), visto desde el Mirador de El Nancito. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011:77 | Cerro Rogatu (toponym in Ngäbere) or Pan de Azúcar (toponym in Spanish), seen from the Mirador de El Nancito. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedies: Legendary Land. Panama: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011: 77.

Remedios era un pueblo de unas cuantas casas, construidas de madera y de la palma de maquenque (Oenocarpus Mart.). Algunas casas eran usadas como abarroterías, que se abastecían con la mercancía proveniente de España, que llegaba mediante los barcos que llegaban continuamente en el Puerto de Remedios.

Cerro Pan de Azúcar (Rogatu) Remedios:Tiera Lejendaria. p.40 Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, David, Chiriquí, Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2012 | Cerro Pan de Azúcar (Rogatu) Remedies: Tiera Lejendaria. p.40 Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, David, Chiriquí, Panama: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2012.

El formidable Gö nunca sufrió en la cárcel, ya que se escapaba de la misma sin que los guardias quienes cuidaban el sitio penal se dieran cuenta del hecho. Y como se volvía en dos personas, siempre se encontraba en alguna parte cuando supuestamente debía estar en la cárcel de Remedios. Cuando menos los guardias pensaban, el Gö aparecía por la calle comiendo pan y otras cosas que sacaba de la tienda sin que el dueño se diera cuenta de lo mismo. Volvían a encarcelarlo, pero resultaba en vano; repetía la misma hazaña, el Gö caminando siempre por la calle de Remedios con su voz característica: “Gö”, de donde proviene su nombre Gö Caballero, por el que verdugos lo conocían.

En esas circunstancias los guardias y los dueños de las abarroterías ya no soportaban con el tiempo a Gö Caballero y buscaban la manera de matarlo. Varias veces intentaron matarlo sin poder realizarlo. Cuando sus enemigos se dieron cuenta de que no podían matarlo a sus antojos y ya cansados de las travesuras y la intranquilidad que provocaba, entonces le preguntaban de qué manera se moría y cómo se debía realizar. Él, ni corto ni perezoso, indicaba el modo en que podía morir. Inmediatamente, sus enemigos lo ejecutaban y no daba resultado.

Sus enemigos, frustrados, le decían que él estaba engañándolos así sucesivamente, intento tras intento, sin poder matarlo. Varias veces trataron de fusilarlo, pero no lo lograron. Lo amarraban en el palo y luego intentaban fusilarlo; pero, en el preciso momento lo encontraban parado en otra parte, sin amarre, con su habla: “Gö”. Es decir que, en el momento de su fusilamiento, se escapaba milagrosamente del lugar, provocando tiros al vacío.

Parece que también Gö se estaba aburriendo de estar en Remedios y, un día, dijo a su ejecutor que ya estaba cansado y que definitivamente iba a dar órdenes e indicar el modo de su ejecución para que muriera. Dijo que la única forma de matarlo era amarrándolo y cubriéndole todo el cuerpo con pajas, hojas y basuras secas; luego, prendiéndole fuego, en el cual se extinguiría por completo y para siempre. Sus verdugos, en su afán de acabar de verdad con su vida, hicieron lo que él dijo y algo más; ellos, antes de prenderle fuego, lo bañaron todo con kerosín para que se encendiera más rápido y se volviera ceniza. Cuando le pusieron fuego, para sorpresa de los guardias y de los observadores, el Gö se volvió en llamas, se levantó y fue prendiendo fuego a cada casa hasta convertir en enorme llamas la población. Luego, se elevó con enorme ruido, tirándose al océano Pacífico, por encima del cerro que aún conserva su nombre para los Guaymí (Ngäbe) “Rogatu”, cayendo en el mar para siempre.

Los Guaymíes (Ngäbe) recuerdan éste como el peor incendio que destruyó el pueblo de Remedios, provocado por el formidable Rogara Meto, en respuesta al empeño de sus enemigos por acabar con su vida como suguiá y como brujo.

Cerro Rogatu (topónimo en ngäbere) o Pan de Azúcar (topónimo en español) desde el cual Gö Caballero se arrojó al Océano Pacífico

Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011:77 | Rogatu (toponym in ngäbere) or Pan de Azúcar (toponym in Spanish) hill from which Gö Caballero threw himself to the Pacific Ocean

Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011:77.

Foreword

FOREWORD

To facilitate reading in Ngäbere, we have adapted, with some modifications, the system in the short Ngäbere-Spanish dictionary Kukwe Ngäbere by Melquiades Arosemena and Luciano Javilla, published in 1979 by the Directorate of Historical Heritage of the National Institute of Culture (INAC), now the Ministry of Culture, and the Summer Institute of Linguistics.

It should also be clarified that this story comes from narrators residing in the village of Potrero de Caña, formerly the Tole district of the Chiriquí province, now the Müna district of the Ngäbe Buglé region, from which the Agronomist Roger Séptimo, the compiler and writer is a native. Consequently, the phonology corresponds to the dialectal or regional variation "Guaymí del Interior" (Pacific slope) which differs from the "Guaymí de la Costa" (Caribbean slope of the province of Bocas del Toro and the now district of Kusapin in the Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) in the Guaymí Grammar of Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, published in 1980 by Fe y Alegría. This variant corresponds to what Arosemena and Javilla call "Chiriquí" and which contrasts with the Caribbean variants of Bocas del Toro and the coast of Bocas.

This ethnohistory was published in 1986 in Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere / Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Ethnohistory Guaymí), by the Panamanian Association of Anthropology, with the PN-079 Agreement of the Inter-American Foundation (FIA) managed by Dr. Mac Chapin, Anthropologist, who encouraged us to follow the example he had set by compiling Pab-Igala: Histories of the Kuna Tradition, published in 1970 by the Center for Anthropological Research of the University of Panama, under the direction of Dr. Reina Torres de Araúz.

This book represented the work of the Agricultural Engineer Roger Séptimo, when he was a student in his second year at the Center for Agricultural Teaching and Research in Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, University of Panama (FCAUP), not only writing in Ngäbere the stories that he had heard from his family members in his community, but also his effort to translate them into Spanish as a bilingual person that he is, like other indigenous people in Panama, who are striving to receive a formal education.

The ethnohistories were compiled, recorded on cassettes and written by the Agronomist Roger Séptimo in 1983 and 1984.

As Professor-Researcher of Anthropology and Rural Sociology at the CEIACHI of the FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Anthropologist, Ph.D., encouraged Roger, as one of her students, to write the stories, convince him and show him that she would not exploit or abuse his work, but that he would get credit. Consequently, the anthropologist limited herself only to making some corrections of form and style in the Spanish translations without altering their content.

We encourage students from the seven indigenous peoples in the Republic of Panama, and teachers in public and private schools, colleges and universities in Panama, to write in their own languages and translate the ethnohistories and songs they hear in their families and communities into Spanish, as part of their informal education.

We also encourage readers of these ethnohistories in Ngäbere, Spanish and English, to draw the scenes that they liked the most, as they did in 2002, students in an Education and Society course, directed by Dr. Joly, at the Faculty of Education, Autonomous University of Chiriquí.

Article 13 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, approved by the General Assembly, in its 107th plenary session on September 13, 2007:

- Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, promote and pass on to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to name and maintain their communities, places and people.

- The States shall adopt effective measures to ensure the protection of this right and also to ensure that indigenous peoples can understand and make themselves understood in political, legal and administrative actions, providing for this, when necessary, interpretation services or other appropriate means.

ROGARA METO OR GÖ CABALLERO

This character was a suguiá who lived in the mountain ridge between the districts of Tolé (now Muna, Comarca Ngäbe Bugle) and Remedios.

En el lado izquierdo del mapa del distrito de Remedios está el río San Félix que divide el distrito de San Félix del distrito de Remedios. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros Olimpia Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2011:34 | On the left side of the map of the district of Remedios is the river San Felix that divides de district of San Félix from the district of Remedios. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros Olimpia Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2011:34.

He had a very particular characteristic, by which almost all the indigenous people who lived in that area knew him. It is said that he could become two persons or could be in two different places at the same time.

In times of the colonization and until a few days ago, the suguiás were persecuted by the colonizers, and after by their descendants, because, according to them, they were witches who attacked their expeditions, ruined their projects, produced failures, and did not let them be in peace. And any other phenomena that occurred to them, as they did not know its origins and the reason of the same, then it was blamed on the suguiás, considering them as witches. Nowadays, inclusive, they are considered the same way by non-indigenous elements.

This motivated the colonizers, the creoles, and their descendants to maintain an arduous campaign to liquidate all the suguiás who were living in the Guaymí (Ngäbe) region. They made constant trips by the mountain ridge in search of the suguiás, making surveys, interviewing the indigenous people so that they would give them information about the existence of suguiás, to look for them and take them to the city, to then put them in jail or even kill them, with the intention of gradually eliminating the suguiás (witches), to avoid disagreeable and negative phenomena in their efforts to own the lands and natural resources of the indigenous people.

The Guaymies (Ngäbe), in their efforts to safeguard the physical integrity of the suguiás, very little or nothing said to the investigators. For that reason, their enemies, and strange elements, non-indigenous, very little knew about suguiás; there is nothing written about them, and, if there is, it has not been revealed to strange elements of the indigenous people in order to keep it occult.

Such were the circumstances in which Gö Caballero had to live, confronting the inclemency of those times. It seems that, in the search for suguiás, they found Gö Caballero and took him as a prisoner, taking him to the headquarters in Remedios where he would pay his fault for his witchcraft. But the notable Rogara Meto or Gö Caballero, did not even consider it important and only limited himself to follow the guards to go to jail.

Cerro Rogatu (topónimo en ngäbere) o Pan de Azúcar (topónimo en español), visto desde el Mirador de El Nancito. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011:77 | Cerro Rogatu (toponym in Ngäbere) or Pan de Azúcar (toponym in Spanish), seen from the Mirador de El Nancito. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedies: Legendary Land. Panama: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011: 77.

Remedios was a town with some houses built of wood and with roofs of the maquenque palm (Oenocarpus Mart.). Some houses were used as grocery stores, that were supplied by the merchandise coming from Spain, that arrived in the ships that continuously arrived at the port of Remedios.

Cerro Pan de Azúcar (Rogatu) Remedios:Tiera Lejendaria. p.40 Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, David, Chiriquí, Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2012 | Cerro Pan de Azúcar (Rogatu) Remedies: Tiera Lejendaria. p.40 Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, David, Chiriquí, Panama: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2012.

The formidable Gö never suffered in the jail, as he would escape from it without the guards who guarded the penal site becoming aware of the fact. And as he could become two persons, he could be found in some other part when supposedly he should have been in the jail of Remedios. When the guards less thought, Gö would appear on the street eating bread and other things that he would take out of the store without the owner becoming aware of it. He would be put in jail again, but it was in vain; the same feat would repeat, Gö would always be walking on the street of Remedios with his characteristic voice “Gö”, from which comes his name Gö Caballero, by which the executioners knew him.

In such circumstances, the guards, and the store owners, with time, could not stand anymore Gö Caballero and were looking for a way to kill him. When his enemies became aware that they could not kill him at their will and tired of his mischief tricks and the intranquility that he caused, then they asked him in which way he would die and how could it be realized. He, without hesitation, would indicate the way in which he could die. Immediately, his enemies would execute it without any result.

His frustrated enemies would tell him that he was deceiving them successively, intent after intent, without being able to kill him. They would tie him to a pole and would then try to shoot him, but, at that precise moment, they would find him standing in another part, without being tied, and saying “Gö”. That is, at the moment of the shooting, he would miraculously escape from that place, provoking firing in the air.

It seems that Gö was also becoming bored of being in Remedios and, one day, he said to his executioner that he was tired and would definitely give orders and indicate the way to execute him so that he could die. He said that the only way to kill him was to tie him and cover all his body with straw, dry leaves, and garbage, and then burn him, by which he would be completely extinguished forever. His executioners, in their desire to really finish with his life, they did what he said and more; they, before burning him, bathed him in kerosene so that he would burn faster and become ashes. When they put fire on him, for the surprise of the guards and the observers, Gö was covered with flames, rose, and went jumping over each house, burning the roofs, until the whole town was in flames in an enormous fire. Then, he elevated himself with an enormous sound, throwing himself into the Pacific Ocean, from the top of the hill that still conserves his name “Rogatu”, for the Guaymí (Ngäbe), and fell into the ocean forever.

The Guaymies (Ngäbe) remember that this was the worse fire that destroyed the town of Remedios, caused by the formidable Rogara Meto, in answer to the intentions of his enemies to finish with his life as a suguiá and as a witch.

Cerro Rogatu (topónimo en ngäbere) o Pan de Azúcar (topónimo en español) desde el cual Gö Caballero se arrojó al Océano Pacífico

Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011:77 | Rogatu (toponym in ngäbere) or Pan de Azúcar (toponym in Spanish) hill from which Gö Caballero threw himself to the Pacific Ocean

Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011:77.

Rogara Meto, ne abogo suguia kä nomlen nünen niguen ngüitdara tda temen kä gä Remedios, Tolé matare nebiti temen. Suguia ne abogo ñó garera ngäbe nünangä kä ne gonti ye, nie nomlen abogo, ñara nomlen nigüite nibu erenguare abogo toa nomlen kä madabiti temen amlen ñara nomlen kä madabiti ne amlen. Kueguebe güi amatibe toa nain ne amlen kä mada gonti.

En el lado izquierdo del mapa del distrito de Remedios está el río San Félix que divide el distrito de San Félix del distrito de Remedios. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros Olimpia Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2011:34 | On the left side of the map of the district of Remedios is the river San Felix that divides de district of San Félix from the district of Remedios. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros Olimpia Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2011:34.

Sulia jatalin nain kena temen biti kä nügue ne. Nomlen nain suguia jiöbiti niguen ngäbe jutaite temen. Nomlen kete brujubata, nomlen ngäbe brujo niere abogo nomlen rüre bentre, kä nomlen gainte, nomlen kugüe nuenen bätägä nguarebe bata nieguen kon senta, ñan nomlen toemlen kaibe, nomlen nain jiöbiti.

Sulia abogo, ñó bata, ñó röbäre kugüe nomlen ñögaingä bata abogo ñan nomlen nügüe gare ietre abogo nomlen kite mada suguiabiti, abogo nomlen nigüite brujure abogo nomlen nain temen jiöbiti, ne krere, kädrie tä matare, nie tä suliagüe. Ne abogo bata sulia nomlen nain kisire suguia ngälenne niguen konsenta temen ngäbe griéte, ne abogo kuandre ie abogo müre ketadre kue gäre, ne krere rigadre nuenen niguen temen abogo brujo ngäbere ne müreketadre jogrä kuetre gäre namanlin nain konsenta. Namanlin nain kisere niguen konsenta temen suguia kälenen, ngüentari niguen temen ngäbeye, medente suguia nomlen nünen gare ngäbeye ya nomlen nebe ngüentari. Ne abogo niedre ietre abogo janandre suguia toen griéte abogo biti migadre ngüite kuetre gäre o kä migare kuetre, ne krere. Abogo bokon suguia rigare nengätre jogrä gäre. Ne krere abogo kägüe brujo ngäbere kitadegä jogrä amlen rabaitre nain jämen, amlen-brujo ñan rabai nebe mige ngälienen, ñan rabaí nebe migue ngälienen, ñan rabaí kugüe noenen bätägä nguarabe batatre.

Ne abogo bata ngäbe namanlin suguia driere ñagare ietre, rügantde nomlen jiriäbe kälintre, suguia nünen ñagare nere temen nie nomlen ietre. Amlen kädrie ñagare bentre, nie ñagare sulia mada ye, kädrie ñácara bogon suliabe. Ne abogo bata matdare gare ñagare sulia ye, ne ni ñó gare ñagare suliaye metre.

Ñan nieta ietre, rügantdeta jiriäbe kälin ne abogo ngäbe be ie gare niguen temen, abogo kädriere ñacara ni nguarebebe. Sulia nomlen nain krörö suguia jiöbiti niguen konsenta amlen Gö güe nünambare.

Ne abogo sulia nomlen nain ne krere kontdi ngötdalin Göbe kontdi migalin ngüite kuetre biti jäniga lintre kue Remedios kontdi miguei ngüite käre kuetre gäre; brujo bata.

Ne abogo Gö güe tebaibare ñácara nigalin jiriäbe bentre jutdaguäre. Jutda Remedios ne nguare abogo ju kuati kuati krire niguen temen.

Cerro Rogatu (topónimo en ngäbere) o Pan de Azúcar (topónimo en español), visto desde el Mirador de El Nancito. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011:77 | Cerro Rogatu (toponym in Ngäbere) or Pan de Azúcar (toponym in Spanish), seen from the Mirador de El Nancito. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedies: Legendary Land. Panama: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011: 77.

Jorágä be bigalin jure niguen temen, të jondron rürübain nomlen sulia güe. Jondron ne abogo jänomlen nügue ñö gäte mötda Rugüe, España nomlen nügue mrenbiti Remedios tda temen käntdi.

Cerro Pan de Azúcar (Rogatu) Remedios:Tiera Lejendaria. p.40 Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, David, Chiriquí, Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2012 | Cerro Pan de Azúcar (Rogatu) Remedies: Tiera Lejendaria. p.40 Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, David, Chiriquí, Panama: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2012.

Gö namanlin ñagare ngüite suliaye, ñara nomlen ngüite ta ñäre ñäcara sulia gän. Nomlen nigüite nibu aicete abogo miga ngüitde amlen toa niguen kä madabiti, ne amlen ngüitde bä amatibe. Ne amlen ngüite suliagüe Remedios bä amatibe. Nomlen nguitie ta nin ga nomlen suliagüe.

Migalin ngüite abogo, nguibia suliagüe amlen batibe rábara diguegä jutdate temen jondron güetde, pan güete erenguanen, ne abogo ñara nomlen dengä gore niguen tientdatde temen sulia gän ñare ñácare tari. Nomlen den ñó nin ganomlen suliagüe. Ne abogo kuan juta nguäre kontdi ka nomlenta, miga nomlenta ngüite buguta, ne be jäglun. Nomlen nguitieta ta nainta juta nguäre Remedios jondron güete gore, ne bata kugüe. Gare kuin “Gö” nie kue rábara diguegä jibitise. Kugüe nebiti kä mialin ribanga suliaregüe, biti nomlen käden.

Ne abogo bata ribanga migagä ngüite, tienta bogon jatalin nainte, kisete kä tö namanlin kä migai mada. Nuembare bäre bäre kuetre nin namanlin müreketalin ietre. Namanlin kämigare tare krägätre amlen nanlinte Gö guisete, ñan nguannamanlin nebe nuäre Gögüe, amlen niebaretre kue Göye, Gö nuendre amlen götadre namanlin niere Göye, ja nuendre amlen ja götadre niebare ie Gö güe mada.

Ne krere nuen nomlen Gö bata kuetre bogonlen akua nin Gö nomlen nebe müreketalin ietre ne be jäglun, abogo bata ribanga gräñan namanlin nuendre mrä, ñan namanlin nebe mürekedalin ietre, amlen namanlin nguentari jäglun Gö ye, noendre amlen götadre, ñara nomlen niere noendre amlen götadre.

Ne karere ribanga nomlen nuenen bata akua krere nin nomlen nögaingä. Ne abogo bata bäri ribanga nomlen nebe nainte bata. Gö nomlen ngögue nguanrabe nomlentre nebe niere ie. Ne aibe jäglun bata nin namanlin müre ketalin ietre. Bäre bäre tägalin kürübite kuetre nin namalin bata ietre. Nomlen tägue kürübiti nin kürügüa nomlen nebe bata, jiriäbe kuan nünanlingä move temen nguarabe kö ñacara bata ne “Gö” nie kue. Ne amlen ñara nomlen nguitiete kribata ñäre ñácara tari abogo tä be tägä nomlen ribangagüe kribata. Ne abogo krií diare, mrä Gö jatalin nainte arato grere kägüe niebare mrä ietre, noendre amlen gätadre bogonlen.

Gö güe niebare ietre, kämiga törabadre ribangagüe bogonlen, ne amlen migä nötare, kriä nötare mägädre ere bata biti kerosin guiare te biti oguäbügaregä amlen ja rüguain ser ne amlen götare bogonlen niebare kue. Ribanga tö nomanlin toai jötrö nugueinse bogonlen kägüe nöembare bata, ñaragüe niebare krere.

Sribebare kuetre biti kerosin guialin ere te kuetre ne abogo rüguainsere bäri jötrö gäre. Ne biti oguäbügalinga kuetre, Gö oguä nabalingä nigalin betegä jiriäbe oguäbititre nigalin ñüguä guetegä jubata niguen temen, ju oguäbügalingä jogrä kue, namanlin jutdra guitiegä jagrä temen, amlen müre krií ngörabaga sete krere ngö namanlingä, nögalingä kuintda, nigalin rogatübitita, nigalinbe mrente timon käre gäre. Ngäbe nomlen niere, nie tä kä ne nguanre arato.

Gö güe ju kuguanlinse kruguäte Remedios kontdi juta nugualinse jogrä nieta. Ne abogo ribanga nomlen mie ngüite, tö namanlin nüre ketai, nomlen kete brujubata, suguiare abogo bata, abogo däguäre, suguia ne nügalinbiti bentre jabata ne nguan-re.