Hermanos Midi Chali y Juite Chali, secuestrados por los Mosiguis etnias de mundo.com en es.wikipedia.org consultado 29/11/2020 | Brothers Midi Chali and Juite Chali, kidnapped by the Mosiguis ethnic groups from mundo.com in es.wikipedia.org consulted 11/29/2020.

Prólogo

PRÓLOGO

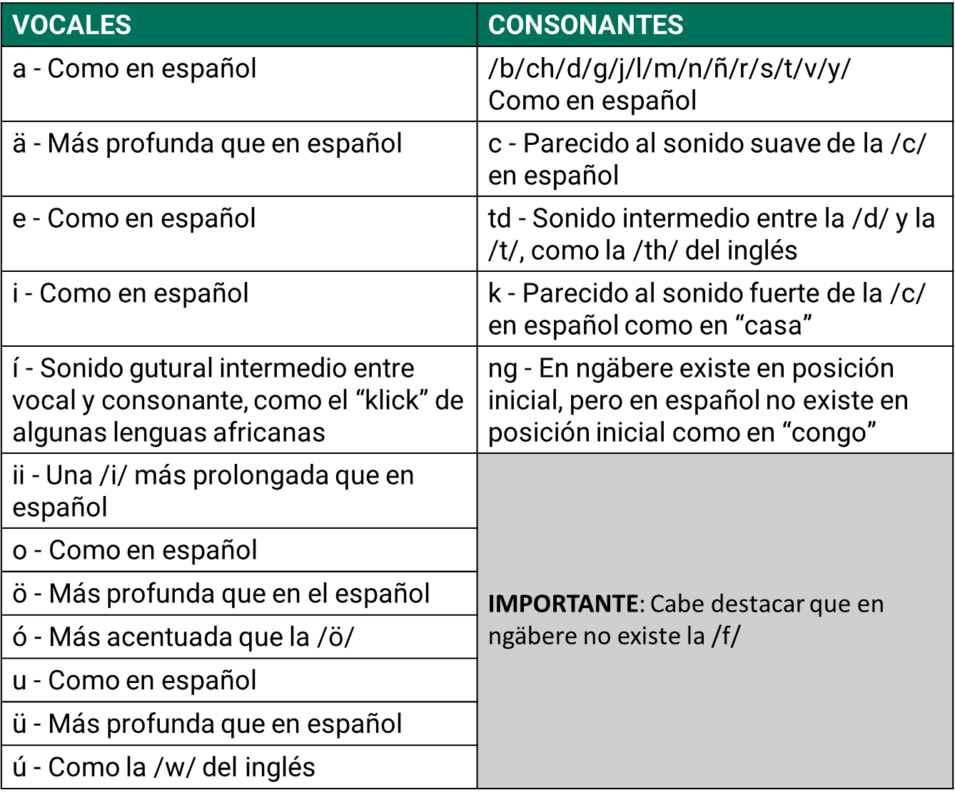

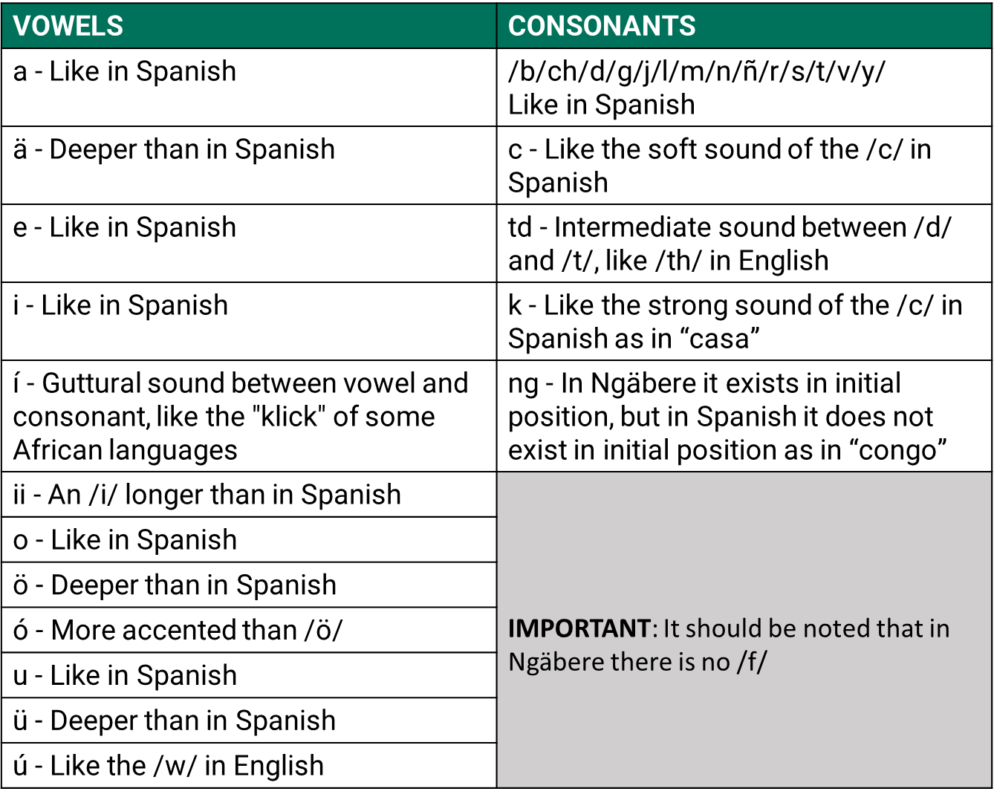

Para facilitar la lectura en ngäbere, hemos adaptado, con algunas modificaciones, el sistema en el breve diccionario ngäbere-español Kukwe Ngäbere de Melquiades Arosemena y Luciano Javilla, publicado en 1979 por la Dirección del Patrimonio Histórico del Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INAC), ahora Ministerio de Cultura, y el Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

También conviene aclarar que esta historia proviene de narradores residentes en el corregimiento de Potrero de Caña, antes distrito de Tole de la provincia de Chiriquí, ahora distrito de Müna de la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé, de donde es oriundo el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, el recopilador-escritor. Por consiguiente, la fonología corresponde a la variación dialectal o regional “Guaymí del Interior” (vertiente del Pacífico) y que difiere del “Guaymí de la Costa” (vertiente caribeña de la provincia de Bocas del Toro y del ahora distrito de Kusapin en la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) en la Gramática Guaymí de Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, publicada en 1980 por Fe y Alegría. Esta variante corresponde a la que Arosemena y Javilla denominan “Chiriquí” y que contrasta con las variantes caribeñas de Bocas del Toro y costa de Bocas.

Esta etnohistoria fue publicada en 1986 en Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere/Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Etnohistoria Guaymí), por la Asociación Panameña de Antropología, con el Convenio PN-079 de la Fundación Inter-Americana (FIA) gestionada por el Dr. Mac Chapin, Antropólogo, quien nos animó a que siguiéramos el ejemplo que él había sentado al recopilar el Pab-Igala: Historias de la Tradición Kuna, publicadas en 1970 por el Centro de Investigaciones Antropológicas de la Universidad de Panamá, bajo la dirección de la Dra. Reina Torres de Araúz.

Este libro representó la labor del Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, cuando era estudiante en su segundo año en el Centro de Enseñanza e Investigación Agropecuaria de Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad de Panamá (FCAUP), no solo de escribir en ngäbere las narraciones que había oído relatar a sus familiares en su comunidad, sino también su esfuerzo de traducirlas al español como persona bilingüe que es, al igual que otros indígenas en Panamá quienes se esfuerzan por recibir una educación formal.

Las etnohistorias fueron recopiladas, grabadas en casetes y escritas por el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo en 1983 y 1984.

Como Profesora-Investigadora de Antropología y Sociología Rural en el CEIACHI de la FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Antropóloga, Ph.D., animó a Roger, como uno de sus estudiantes, a escribir las historias, convencerlo y demostrarle que no explotaría ni abusaría de su trabajo, sino que se le reconocería su mérito. Por consiguiente, la antropóloga se limitó solamente a hacer algunas correcciones de forma y estilo en las traducciones al español sin alterar su contenido.

Animamos a estudiantes de los siete pueblos originarios en la República de Panamá, y a docentes en escuelas, colegios y universidades públicas y privadas en Panamá, a que escriban en sus propios lenguajes y traduzcan al español las etnohistorias y cantos que escuchan en sus familias y comunidades, como parte de su educación informal.

También animamos a lectores de estas etnohistorias en ngäbere, español e inglés, a que dibujen las escenas que más les gustaron, como hicieron en el 2002, estudiantes en un curso de Educación y Sociedad, orientado por la Dra. Joly, en la Facultad de Educación, Universidad Autónoma de Chiriquí.

Artículo 13 de la Declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas, aprobada por la Asamblea General, en su 107ª sesión plenaria el 13 de septiembre de 2007:

- Los pueblos indígenas tienen derecho a revitalizar, utilizar, fomentar y transmitir a las generaciones futuras sus historias, idiomas, tradiciones orales, filosofías, sistemas de escritura y literaturas, y a atribuir nombres a sus comunidades, lugares y personas, así como a mantenerlas.

- Los Estados adoptaran medidas eficaces para asegurar la protección de ese derecho y también para asegurar que los pueblos indígenas puedan entender y hacerse entender en las actuaciones políticas, jurídicas y administrativas, proporcionando para ello, cuando sea necesario, servicios de interpretación u otros medios adecuados.

Así se llamaba el indígena quien fue secuestrado por los Mosiguis en sus constantes excursiones guerrilleras sobre el Istmo de Panamá y, en concreto, por las regiones actualmente conocidas como Bocas del Toro y Chiriquí. Los Mosiguis fueron enemigos de combate por varias décadas de los Guaymíes (Ngäbe). No buscaban expandir, al parecer, su posición geográfica, sino que era más bien sus deseos de cometer cualquier abuso contra grupos indígenas que encontraran en su paso, saqueándolos y matándolos. Para hacer estas hazañas, visitaban lugares lejanos de su procedencia.

Nación Miskita consultado 1/12/2020 es.wikipedia.org | Miskito Nation consulted 1/12/2020 en.wikipedia.org.

Antes de la colonización, y en la plena colonización, estos grupos de indígenas guerreros libraron batallas arduas, de enfrentamiento frontal y sin tregua con los Guaymíes (Ngäbe). Los Mosiguis eran navegantes que solían entrar en la tierra firme por las desembocaduras de los ríos al mar y así atacaban sorpresivamente los campamentos y guarniciones de sus rivales.

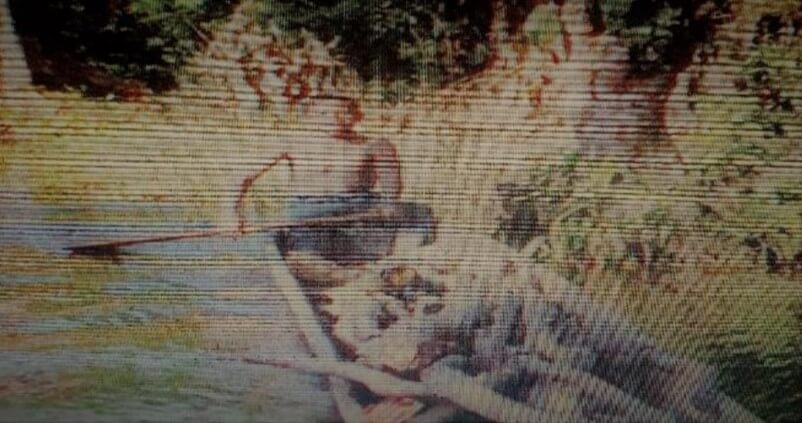

Miskitos palanqueando cayuco. Consultado 1/12/2020 Nación Miskita es.wikipedia.org | Miskitos leveraging cayuco. Accessed 12/1/2020 Miskito Nation es.wikipedia.org.

En una de estas expediciones guerreras, los Mosiguis lograron secuestrar a los dos hermanos Midi Chali y Juite Chali, estando ellos muy pequeños. Los Mosiguis cuidaron a los dos para que luego les sirvieran de espías de los terrenos de combate, campamentos y guarniciones de sus enemigos; es decir, que iban a ser guías de los Mosiguis para atacar a los Guaymíes (Ngäbe).

Pareciera que nadie le daba importancia a la presencia ni procedencia de estos dos individuos. Tal vez echaban de menos su participación entre ellos. Ni siquiera se les ocurría a ellos pensar que estos dos hermanos convivían con los guerreros Mosiguis y sabían de las estrategias para combatir de ellos y la modalidad de sus armas.

Aunque vivieran con los grupos Guaymíes (Ngäbe), cumplían fielmente con los Mosiguis, ya que nunca dijeron de la posibilidad de una excursión de los Mosiguis y ni el porqué de su constante presencia entre comunidades indígenas de la región. Pero, un día, un suguiá se dio cuenta de la misma. Él dejó que pasara tiempo para no darle motivo a Midi Chali que se diera cuenta de su presencia y las intenciones.

Cayuco miskito con palos de mangle. Consultado 1/12/2020 Nación Misquita es.wikipedia.org | Cayuco miskito with mangrove sticks. Accessed 12/1/2020 Misquita Nation es.wikipedia.org.

El suguiá, queriendo comprobar la actitud de Midi Chali, lo responsabilizó para que cuidara de la presencia de la embarcación de los Mosiguis que podía penetrar por la desembocadura de un río muy cercano donde estaba habitando un grupo de indígenas Guaymíes (Ngäbe). La instrucción que le dieron fue la de estar permanentemente vigilando la llegada de cualquier embarcación que estuviera cerca de la costa. Si él lograba observar algo tan pequeño que pareciera como hojas de árboles flotando sobre el mar, que avisara inmediatamente al suguiá ya que era la presencia de los Mosiguis. Después que le encomendó este trabajo, el suguiá vigilaba continuamente a Midi Chali, pero sin que él se diera cuenta.

El suguiá se dio cuenta de varias embarcaciones que llegaron a la desembocadura del río, pero Midi Chali no le decía nada. El suguiá sabía esto antes que ocurriera y antes de encargarle a Midi Chali que reportara las embarcaciones. Así que el suguiá sólo se limitó a ir a visitar la tropa de los Mosiguis que ya estaba en tierra y en camino para combate.

Pero, para hacer esta inspección, el suguiá tenía que volverse como Mosigui mulato, para poder lograr entrar en el campamento de los Mosiguis sin pasarle nada. Así hizo su maniobra y luego regresó a su campamento. En su recorrido entre los Mosiguis, se dio cuenta de la cantidad de los Mosiguis que habían llegado, que era una cantidad numerosa. Al llegar a su campamento, manifestó lo que estaba pasando y dio orden para que todos los que estaban en el campamento se prepararan para el combate con los Mosiguis. Buscó una hora en que los Mosiguis estaban todos en descanso, para poder agarrarlos todos y matarlos sin dejar a ninguno vivo.

Ellos se prepararon y se fueron a ver a los Mosiguis y también llevaron a Midi Chali sin que él se percatara de la acción que iban a realizar. Ni siquiera el suguiá le llamó la atención a Midi Chali, sino que todo lo dejó para lo último. Parece que Midi Chali se reunía con los Mosiguis por las noches y les decía a ellos como estaban preparados sus rivales y el tiempo en que podían ser víctimas de los Mosiguis sin que pudieran ofrecer resistencia. Según esto, los Mosiguis iban a atacar por la noche el campamento de los Guaymíes (Ngäbe); pero antes que ellos lo hicieran, lo hicieron los Guaymíes.

Cuando llegaron al campamento de los Mosiguis, los encontraron todos dormidos. Se piensa que esta fue la hazaña del suguiá, para acabar con los Mosiguis. Las embarcaciones de los Mosiguis estaban llenas de pedazos de mangle cortado especialmente para matar a sus enemigos, dándole golpes en las cabezas y acabándolos de una vez para siempre.

Montón de palos de mangle. Mangles de Panamá (Manglares de Panamá), consultado el 12/04/2020 Google | Pile of mangrove sticks. Mangles de Panamá (Mangroves of Panama), consulted 4/12/2020 Google.

La comitiva del suguiá llegó. Sin perder tiempo, tomaron los pedazos de mangle cortados por los Mosiguis y con los mismo le fueron dando a cada uno sin darle tiempo a que despertaran los demás. Hasta, cuando ya quedaron unos pocos Mosiguis, fue que lograron escaparse de la palera que les iba a caer encima.

Monumento al Guerrero Miskito Bilwi. El arco y la flecha eran los brazos principales de los guerreros miskitos. Desde pequeños practicaban con arcos y flechas de juguete que hacían sus padres. es.wikipedia.org consultado el 12/4/2020 | Monument to the Miskito Warrior Bilwi. The bow and arrow were the principle arms of the Miskito warriors. From childhood, they practiced with toy bows and arrows that their fathers made. es.wikipedia.org consulted 4/12/2020.

Se recuerda que esta fue la masacre más grande y la derrota de la misma dimensión que se llevaron los Mosiguis. Después de la matanza, cogieron a los Mosiguis muertos, les abrieron las barrigas y, con las mismas tripas de los Mosiguis, bañaron a Midi Chali. Luego le dieron una rejera soberana por su militancia nociva con los Mosiguis para el grupo Guaymí (Ngäbe). Parece que él no intentó más informar a los Mosiguis y decidió vivir con su grupo. Luego, él hizo u organizó la batalla que asaltó a Tolé, ya que él si sabía el método de ataque y combate de los Mosiguis y los imitó para hacer la hazaña de Tolé, que se le atribuye a los Mosiguis, porque fue un comando al estilo de los Mosiguis, pero eran Guaymíes (Ngäbe). (1)

(1) Los indígenas Mosquitos penetraron en el Istmo, por el Atlántico, procedentes de Nicaragua, por el año 1727. En 1732, invadieron la Villa de David y en 1788 destruyeron Bugaba, Tolé y Cañazas. En la madrugada del 8 de septiembre de 1788, cayeron sobre los misioneros de la reducción de San José de Tolé, pusieron fuego al convento, robaron los vasos sagrados, e hirieron gravemente al Padre Ramón Rábago, como afirma el testigo Fray Diego Montes (Archivo General de Indias, Panamá, Legajo 265, informe del Gobernador de Veraguas sobre las agresiones de los indígenas a Tolé, Bugaba y Cañazas, año 1788).

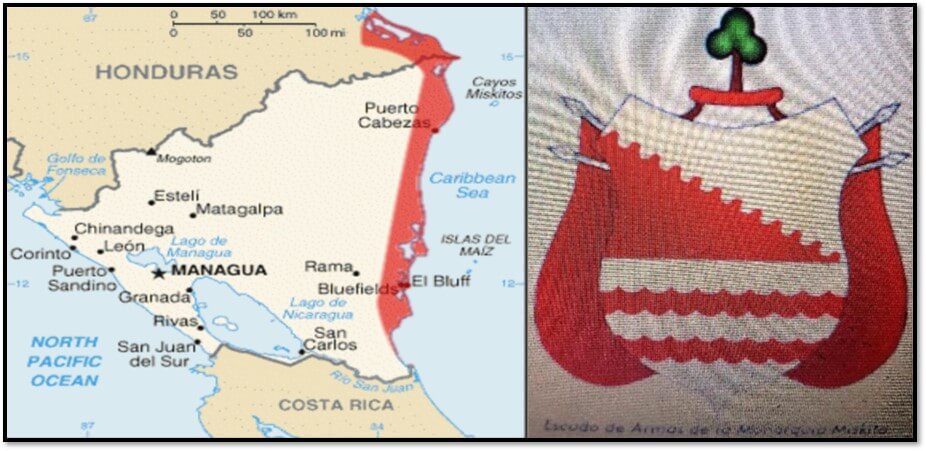

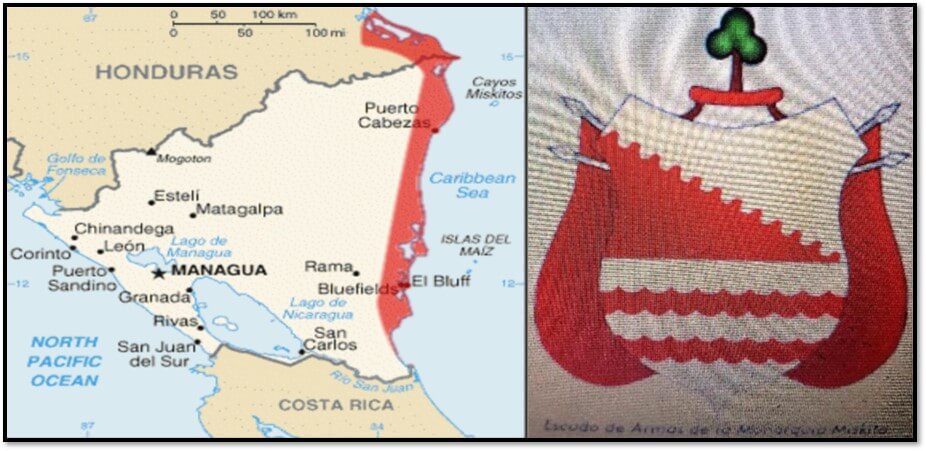

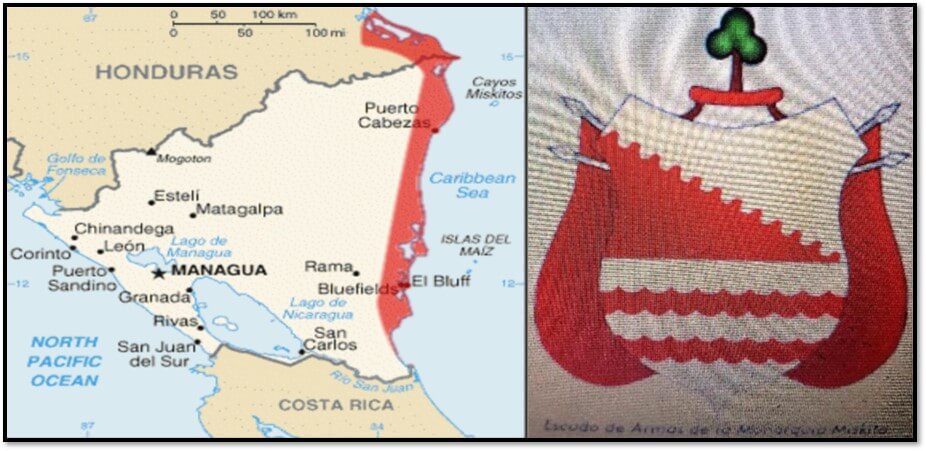

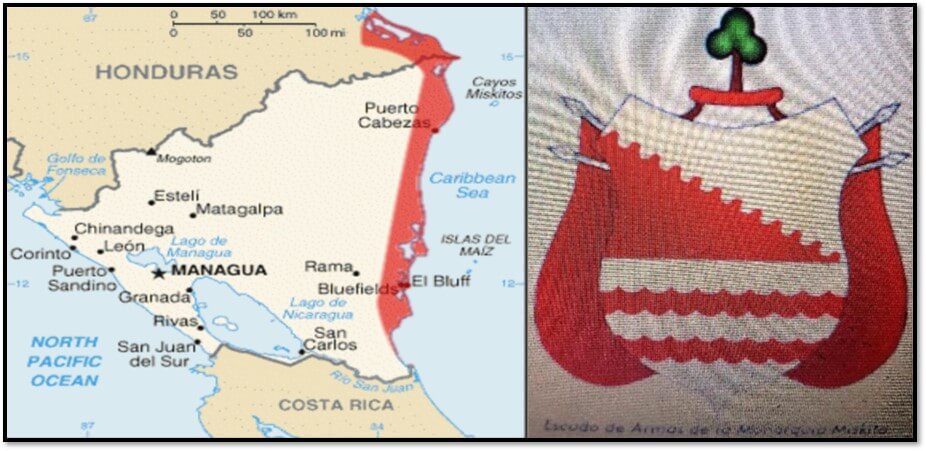

A la izquierda, en rojo, la Mosquetía. A la derecha, Escudo de Armas del Reinado Miskito (es.wikipedia.org consultado 1/12/2020) | On the left, in red, the Mosquetía. On the right, Coat of Arms of the Miskito Kingdom (es.wikipedia.org consulted 1/12/2020).

Hermanos Midi Chali y Juite Chali, secuestrados por los Mosiguis etnias de mundo.com en es.wikipedia.org consultado 29/11/2020 | Brothers Midi Chali and Juite Chali, kidnapped by the Mosiguis ethnic groups from mundo.com in es.wikipedia.org consulted 11/29/2020.

Foreword

FOREWORD

To facilitate reading in Ngäbere, we have adapted, with some modifications, the system in the short Ngäbere-Spanish dictionary Kukwe Ngäbere by Melquiades Arosemena and Luciano Javilla, published in 1979 by the Directorate of Historical Heritage of the National Institute of Culture (INAC), now the Ministry of Culture, and the Summer Institute of Linguistics.

It should also be clarified that this story comes from narrators residing in the village of Potrero de Caña, formerly the Tole district of the Chiriquí province, now the Müna district of the Ngäbe Buglé region, from which the Agronomist Roger Séptimo, the compiler and writer is a native. Consequently, the phonology corresponds to the dialectal or regional variation "Guaymí del Interior" (Pacific slope) which differs from the "Guaymí de la Costa" (Caribbean slope of the province of Bocas del Toro and the now district of Kusapin in the Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) in the Guaymí Grammar of Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, published in 1980 by Fe y Alegría. This variant corresponds to what Arosemena and Javilla call "Chiriquí" and which contrasts with the Caribbean variants of Bocas del Toro and the coast of Bocas.

This ethnohistory was published in 1986 in Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere / Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Ethnohistory Guaymí), by the Panamanian Association of Anthropology, with the PN-079 Agreement of the Inter-American Foundation (FIA) managed by Dr. Mac Chapin, Anthropologist, who encouraged us to follow the example he had set by compiling Pab-Igala: Histories of the Kuna Tradition, published in 1970 by the Center for Anthropological Research of the University of Panama, under the direction of Dr. Reina Torres de Araúz.

This book represented the work of the Agricultural Engineer Roger Séptimo, when he was a student in his second year at the Center for Agricultural Teaching and Research in Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, University of Panama (FCAUP), not only writing in Ngäbere the stories that he had heard from his family members in his community, but also his effort to translate them into Spanish as a bilingual person that he is, like other indigenous people in Panama, who are striving to receive a formal education.

The ethnohistories were compiled, recorded on cassettes and written by the Agronomist Roger Séptimo in 1983 and 1984.

As Professor-Researcher of Anthropology and Rural Sociology at the CEIACHI of the FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Anthropologist, Ph.D., encouraged Roger, as one of her students, to write the stories, convince him and show him that she would not exploit or abuse his work, but that he would get credit. Consequently, the anthropologist limited herself only to making some corrections of form and style in the Spanish translations without altering their content.

We encourage students from the seven indigenous peoples in the Republic of Panama, and teachers in public and private schools, colleges and universities in Panama, to write in their own languages and translate the ethnohistories and songs they hear in their families and communities into Spanish, as part of their informal education.

We also encourage readers of these ethnohistories in Ngäbere, Spanish and English, to draw the scenes that they liked the most, as they did in 2002, students in an Education and Society course, directed by Dr. Joly, at the Faculty of Education, Autonomous University of Chiriquí.

Article 13 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, approved by the General Assembly, in its 107th plenary session on September 13, 2007:

- Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, promote and pass on to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to name and maintain their communities, places and people.

- The States shall adopt effective measures to ensure the protection of this right and also to ensure that indigenous peoples can understand and make themselves understood in political, legal and administrative actions, providing for this, when necessary, interpretation services or other appropriate means.

That is the name of the Indian who was kidnapped by the Mosiguis, during their constant guerrilla excursions on the Isthmus of Panamá, specifically, in the regions now known as Bocas del Toro and Chiriqui. The Mosiguis were enemies of combat, for several decades, of the Guaymi (Ngäbe). Apparently, they did not want to expand their geographical position, but it was rather their desire to commit any type of abuse against indigenous groups that they encountered on their way, plundering and killing them. To do these feats, they visited places faraway from where they came.

Nación Miskita consultado 1/12/2020 es.wikipedia.org | Miskito Nation consulted 1/12/2020 en.wikipedia.org.

Before the colonization and during the colonization, these groups of warring Indians committed arduous battles of frontal opposition, without truce, against the Guaymi (Ngäbe). The Mosiguis were sailors who used to enter inland through the mouths of the rivers in the sea and thus surprisingly attack the camps and garrisons of their rivals.

Miskitos palanqueando cayuco. Consultado 1/12/2020 Nación Miskita es.wikipedia.org | Miskitos leveraging cayuco. Accessed 12/1/2020 Miskito Nation es.wikipedia.org.

In one of these warring expeditions, the Mosiguis managed to kidnap the two brothers Midi Chali and Juite Chali, when they were very small. The Mosiguis took care of them so that later they could serve as spies in territories of combats, camps, and garrisons of their enemies; in other words, the brothers would be the guides of the Mosiguis to attack the Guaymi (Ngäbe).

It seems that nobody gave importance to the presence of these two individuals. Perhaps they missed their participation among the Guaymi (Ngäbe), who did not even think that the two brothers lived with the Mosigui warriors and knew their combat strategies and their types of arms.

Although they lived with groups of Guaymi (Ngäbe), they were faithful to the Mosiguis, as they never said of the possibility of an excursion of the Mosiguis nor of why they were constantly present in the indigenous communities of the region. But, one day, a suguiá became aware of them. He allowed some time to go by so that Midi Chali would not become aware of his presence nor of his intentions.

Cayuco miskito con palos de mangle. Consultado 1/12/2020 Nación Misquita es.wikipedia.org | Cayuco miskito with mangrove sticks. Accessed 12/1/2020 Misquita Nation es.wikipedia.org.

The sugiuá, wanting to verify the attitude of Midi Chali, gave him the responsibility to look after the presence of the boats of the Mosiguis which could penetrate through the mouth of a river close to where a group of Guaymí (Ngäbe) people were living. The instruction that he gave to Midi Chali was to be permanently on the lookout to see if boats were near the coast. If he observed something small that looked like leaves of trees floating in the sea, to immediately notify the suguiá because that was the presence of the Mosiguis. After giving this task to Midi Chali, the suguiá was continuously looking after Midi Chali, but without making Midi Chali aware of it.

The suguiá became aware of several boats that arrived at the mouth of the river, but Midi Chali said nothing. The suguiá knew this before it occurred and before assigning the task to Midi Chali to report the presence of any boat. So, the suguiá only limited himself to visit the troupe of Mosiguis that was already on land and on their way to combat.

But to make this inspection, the suguiá had to look like a Mosigui mulatto, in order to get into the camp of the Mosiguis without anything happening to him. Thus he did his maneuver and then returned to his camp. In going through the camp of the Mosiguis, he became aware of the number of Mosiguis that had arrived, and that was very numerous. When he got to his camp, he told what was happening, and he gave the order that all the Guaymi (Ngäbe) in the camp should prepare for combat against the Mosiguis. He looked for an hour when de Mosiguis were all resting, so as to be able to get them all and kill them without leaving anyone alive.

The Guaymi (Ngäbe) prepared themselves and went to see the Mosiguis and took Midi Chali along without his becoming aware of the action that they were going to do. Not even the suguiá called Midi´s attention, but only left this until the end. It seems that Midi Chali would get together with the Mosiguis at night and would tell them how their rivals were prepared and the time in which they could become victims of the Mosiguis without any resistance. According to this, the Mosiguis were going to attack the camp of the Guaymi (Ngäbe); but, before the Mosiguis could do it, the Guaymi (Ngäbe) did it.

When the Guaymi (Ngäbe) arrived at the camp of the Mosiguis, they found all the Mosiguis asleep. It is thought that this was achieved by the suguiá, to finish with the Mosiguis. The boats of the Mosiguis were full of mangrove sticks which had been cut specially to kill their enemies, beating them on the heads and finishing them forever.

Montón de palos de mangle. Mangles de Panamá (Manglares de Panamá), consultado el 12/04/2020 Google | Pile of mangrove sticks. Mangles de Panamá (Mangroves of Panama), consulted 4/12/2020 Google.

The retinue of the suguiá arrived. Without losing time, they took the mangrove sticks that had been cut by the Mosiguis and, with the same sticks, they began hitting each one without giving time for the rest to wake up. When there were only a few left, then the rest managed to escape from the beatings that were going to fall on them.

Monumento al Guerrero Miskito Bilwi. El arco y la flecha eran los brazos principales de los guerreros miskitos. Desde pequeños practicaban con arcos y flechas de juguete que hacían sus padres. es.wikipedia.org consultado el 12/4/2020 | Monument to the Miskito Warrior Bilwi. The bow and arrow were the principle arms of the Miskito warriors. From childhood, they practiced with toy bows and arrows that their fathers made. es.wikipedia.org consulted 4/12/2020.

It is remembered that this was the biggest massacre and defeat of the same dimension that the Mosiguis had. After this killing, the dead Mosiguis were picked up, their bellies were opened, and, with the same guts of the Mosiguis, Midi Chali was bathed. Then they gave him a sovereign lashing for his noxious militancy with the Mosiguis, against the Guaymi (Ngäbe). It seems that he did not intent to inform the Mosiguis anymore and decided to live with his group. Afterwards, he made or organized a battle that assaulted Tolé, since he knew the method of attack and combat of the Mosiguis, which he imitated to do the heroic feat in Tolé, that is attributed to the Mosiguis, because it was a commando in a Mosigui style, but were Guaymíes (Ngäbe). (1)

(1) The Miskitos penetrated the Isthmus, by the Atlantic side, coming from Nicaragua, in the year 1727. In 1732, they invaded the Villa of David, and in 1788 destroyed Bugaba, Tolé, and Cañazas. In the dawn of the 8th of September of 1788, they fell upon the missionaries in the reduction of Saint Joseph of Tolé, burned the convent, stole the sacred vessels, and badly injured Father Ramón Rabago, as is affirmed by the witness Fraile Diego Montes (General Archives of the Indies, Panama, Foil 265, Report of the Governor of Veraguas about the aggressions of the Miskitos in Tolé, Bugaba, and Cañazas, year 1788).

A la izquierda, en rojo, la Mosquetía. A la derecha, Escudo de Armas del Reinado Miskito (es.wikipedia.org consultado 1/12/2020) | On the left, in red, the Mosquetía. On the right, Coat of Arms of the Miskito Kingdom (es.wikipedia.org consulted 1/12/2020).

Hermanos Midi Chali y Juite Chali, secuestrados por los Mosiguis etnias de mundo.com en es.wikipedia.org consultado 29/11/2020 | Brothers Midi Chali and Juite Chali, kidnapped by the Mosiguis ethnic groups from mundo.com in es.wikipedia.org consulted 11/29/2020.

Midi Chali ne abogo ngäbe goibare mosiguigüe nomlen nügue rüre ngäbebe kä nebiti nguan-re, nomlen nügue segri, negri, kä gädianta matare suliare Bocas del Toro, Chiriquí kontitda temen nomlen nügue rüre ngäbebe. Ngäbegüe rübare bärebäre mosiguibe, kä nebiti te ñan namanlin nügue, ne abogo ñan tö nomlen nebei kä dengä, amlen kä nguarabetre biti, tö rubata be käre, tö jagabata ribangabe abogo tari käre nain, ne krere abogo nomlen ja toen ngäbebe kä nebata. Nomlentre nain gogäre, ja müreketare gäre ribangabe abogo nain. Tö rübata, tö ribanga migabata nguarabe jai abogo tari nomlen naintre temen, nebetre move temen rüre, ño kärera nomlen nain.

Nación Miskita consultado 1/12/2020 es.wikipedia.org | Miskito Nation consulted 1/12/2020 en.wikipedia.org.

Sulia ngämin nügue kä nebiti amlen mosigui nomlen nügue, biti sulia nügalin-nan kä nebiti amlen nomlen nügueta nen ngäbeye. Rü nemen ñákara ietre. Mosigui abogo ie non gare mrenbiti aicete nomlen kite rute mrenbiti abogo kite ñö gä biti jate, abogo nebe nen ribanga, jutaite, güíriete ie jateta temen käbube nguarabe, ribanga jämen ietre nomlen nebe nen, ne abogo ribanga müre ketare kuäräbe kuetre abogo gäre nomlen noenentre, ne krere rüre käre. Ne krere mosigui nomlen nügue nen ngäbe ye segri konti ngäbägre ja etebare goibare nibu kuetre, Midi Chali bata Nguite Chali.

Miskitos palanqueando cayuco. Consultado 1/12/2020 Nación Miskita es.wikipedia.org | Miskitos leveraging cayuco. Accessed 12/1/2020 Miskito Nation es.wikipedia.org.

Nomientre kia nguan-re, mosigugüe nguibiabare biti kriígri amlen nomlen ngüen jabetre, abogo juen ngäbe toembiti ja kälin. Ngäbe nünen ñó, nomlen ñó, bä ñó jabata abogo juen toembititre, ne abogo biti jataretre nen ietre gäre nomlen nuenen. Midi Chali abogo nomlen nügueta ngäbe ngötaite akua ngäbe abogo tebaire ñácara, nomlen nain nguarabe nomlentre nütre abogo bata nguibiaretari ñácara. Ne abogo nain mosigui be abogo gare ñácare ietre, mrägä abogo ie nüguetre jämen, ne amlen nünen ñó tre, guiere rügrä kuetre, rüre bä ñó abogo gare kuin mosigui ye, abogo Chalibo ne guebeite. Nünen ngäbebe ya o ñó akua neguete mosiguibe, ne aicete mosigui mie totde jai, abogo bata nünen mosiguibe ne abogo niere ñácara, mosiguigüe niaretre mrägaye niere ñácara ietre. Bata nomlen nebe guiere noenen ngäbe ngontitatemen niere ñácara arato.

Akua abogo suguia nomlen ñünen iti kä ne nguan-re kägüe galin, akua ne abogo kägüe niebare ñagare mrägäye namanlinbe kueguebe guibiare jiriäbe. Suguia abogo kägüe ñägäbare ñagare arato Midi Chali ye, toalin-mlen kueguebe kue, namanlin kä migue niguen raire ta, abogo ñan gare Midi Chali güe gäre, abogo bata ñan mialin mogre kenabe kue, nomlen nünen jämen bentre jiriäbe. Suguia tö namanlin Midi Chali töi ñó gai mada, guiere noendi kue abogo tö namanlin gai kägüe mialin ru mosiguigüe guibiare mrenbiti moda, nanlen mosigui riga ñö gäbiti jate nen ngäbeye abogo ñan gä ngäbegüe abogo ngänlienen Midi Chali mialin nguibiare, ne abogo kägüe ru mosigui güe gadre, kägüe niedreta jotrö suguia ye abogo gäre.

Suguiagüe niebare Midi Chali ye: magüe ru nguibia mogre mrenbiti temen, magüe ñan tö guan nügue ñö gäte moda, jata mai move mrenbiti amlen jötro nguarabe magüe drieta tie, niebare ie suguiagüe. Kriä krere raba toen nögaingä move mrenbiti temen mai amlen magüe drie jötrö nguarabe tie, niebare ie suguiagüe, ne amlen mosigui nügue ja ken. Suguia güe niebare krörö ie biti suguia namanlin guibiare, guiere noendi kue abogo suguia tö namanlin gai kägüe mialin, akua suguia güe toalimlen kaibe. Ne abogo ñan gare kue jabata gäre, ne krere gain ñácara jabata bogänlen. Ne biti suguia namanlin guibiare kä bube nguarabe. Suguia oguäbiti ru jatalin nügue kabre möda, Midi Chali güe galin akua niebare ñagare kue suguiaye. Ne abogo noendi kröro kue galinra suguiagüe, kägüe mialin aicete namanlin guibiare arato. Suguiagüe ñägäbare ñagare ie, te suguia nigalin jiriabe mosigui ñügalin kuatií jabata mötda abogo nigalin toembiti. Ne abogo ñan gadre mosiguigüe gäre abogo nigüitalin mosigui mulatore nigaln toembiti. Niguitalin mosigui mulatore janamlen mosigui toembiti biti jatalinta guä. Mosigui nügalin nibe jabata abogo janamlen toembiti, nombare jogrä kue mosigui ngötaitde. Mosigui abogo kägüe galin ñácara jabata.

Cayuco miskito con palos de mangle. Consultado 1/12/2020 Nación Misquita es.wikipedia.org | Cayuco miskito with mangrove sticks. Accessed 12/1/2020 Misquita Nation es.wikipedia.org.

Namanlinta guí kägüe mosigui nomlenn bä ñó jabata mötda niebare kue mrägä ye biti nigalin rü göböire mosiguibe, rüdi ñó mosiguibe erere niebare kue mrägäye.

Ne abogo rüdre mosiguibe, ngualen mosigui tädre kibien jográ nguanre niebare suguiagüe. Ne abogo tädre kibien jogrä bata rabadretre konti kämigadrete jogrä kuetre gäre. Ja ügalingretre kuatií jabata kuetre 7 biti nigalin nen mosiguiye. Ne abogo niere ñagare Midi Chali ye. Nigalintre amlen suguia nigalin Midi Chali ngüenan arato, ne amlen namanlinnan gäre mrägäye.

Akua Midi Chali abogo jänigalin ñó gäre galin ñagare kue, amlen niebare ñagare arato kuetre ie, ne abogo suguia güe ñan nie mlan ie. Ne abogo gadi batibe mötda kue gäre ñan niebare ie. Ne amlen ñan Midi Chali nomlen nebe dego mötda mosigui ngonti, abogo dirire ietre.

Ngäbe nomlen nünen ñó, ne abogo ñó-nguälen kadre jämen mosiguigüe konti müre ketadretre kuäräbe kuetre, abogo nomlen nebe niere mosigui ye mötda.

Montón de palos de mangle. Mangles de Panamá (Manglares de Panamá), consultado el 12/04/2020 Google | Pile of mangrove sticks. Mangles de Panamá (Mangroves of Panama), consulted 4/12/2020 Google.

Ne abogo nomlen nebe kädriereta mosiguibe, ne abogo mosiguigüe niadre dibire ngäbeye ne abogo nomlen kadriere bentre. Ne bata abogo nanlen noentre kue abogo ngälienen kälin, näire rare suguiagüe niabare kälin ngäbebe ietre.

Suguia nigalin nen mosiguiye ngäbe jänigalin kuatií jabe kue. Namanlin mötda mosigui ngontdi, amlen mosigui kuan-lintre kibien jogrä ietre ümanbiti mren gräbiti mötda. Ne abogo suguiagüe mosigui mialin kibien jogrä nieta, suguiagüe köbö dialintre ie kägüe mialin kibien jogrä rare, ne abogo tö namanlin kämigaitre jogrä kägüe noembare krörö mosiguiabata.

Amlen ru jänügalin kratií mosiguigüe té Degueta tigalingä mürüre oto mrämen-be, ügalin ere rute kuetre, nomlen mren gräbiti mötda bäre temen nomlen kibientre, bata ngäbe namanlin suguiabe. Ne abogo kríoto nebeti rigadre ngäbe mete doguägäte konti rigadre kämiguetre kringräbiti jogrä abogo gäre nomlen nguentre. Suguia namanlin ngäbebe bata kägüe jötrö nguarabe Degueta oto mrügalimbata mosiguigüe dialintre kue biti nigalin mosigui kibien temen metde doguägäte. Mosigui kämigalin-ra kuatií kuetre amlen jatalin nüguetre nguäte, mosigui namanlin braibe jabata, ñügalintre nguätetre erere kägüe rüe galintre jabata nigalin betegä, nagualin rute, nigalintre nguitie ngabe ngälienen, ne krere ñan noendretre kue götai jogrä ngäbe kisete. Nieta ngäbegüe abogo ne nguanlen mosigui nialinte ngäbebe jabata amlen ngötalin kuatií 8 amlen ngäbe abogo nomlen ngöi jabata nguidialin ñagare mosigui ye. Ne abogo noembaretre kue Midi Chali oguäbiti.

Monumento al Guerrero Miskito Bilwi. El arco y la flecha eran los brazos principales de los guerreros miskitos. Desde pequeños practicaban con arcos y flechas de juguete que hacían sus padres. es.wikipedia.org consultado el 12/4/2020 | Monument to the Miskito Warrior Bilwi. The bow and arrow were the principle arms of the Miskito warriors. From childhood, they practiced with toy bows and arrows that their fathers made. es.wikipedia.org consulted 4/12/2020.

Nebiti mosigui nguägä temen ngrie nguialingä kuetre jañate biti dorie, ngongrä dialin kuetre te Midi Chali juaglinte kuetre jañäte biti kuata metalin kuetre.

Ne krere moendi kuetre abogo gäre jatalin nguenan arato, aicete niebare ñagare kuetre Midi Chali ye. Negueta doguäre mosiguibe kügüe bare krörö bata.

Mosigui abogo ngäbe rüe ben nomlen neguete abogo bata kügüe noembare krörö mrägä ngäberegüe bata. Ne amlen batibe ñan namanlin neguete mosiguibe.

Amlen namanlinta rünen käre mrägäbe. Nebiti kä nigalin kirara ta amlen Midi Chali arabe kägüe niabare dego suliaye Tolé nieta ngäbegüe. Ne ngualen abogo niabare ngäbe ben kue suliaye. Ñara abogo ie mosigui rüre ñó gare kuin aicete abogo ñaragüe rü göboi migalintibe suliabe, abogo biti mosigui rüre krere noembare tre kue, kägue sulia jualintare, sulia kuata metalin dego Tolé nieta, ja kugüe mialin kuetre mosigui krere aicete nieta suliagüe abogo mosiguigüe niabare Tolé abogo kädri meguera. Kugüe ne abogo suliare abogo nieta krörö.

A la izquierda, en rojo, la Mosquetía. A la derecha, Escudo de Armas del Reinado Miskito (es.wikipedia.org consultado 1/12/2020) | On the left, in red, the Mosquetía. On the right, Coat of Arms of the Miskito Kingdom (es.wikipedia.org consulted 1/12/2020).