Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011:50 | Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedies: Legendary Land. Panama: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011: 50

Prólogo

PRÓLOGO

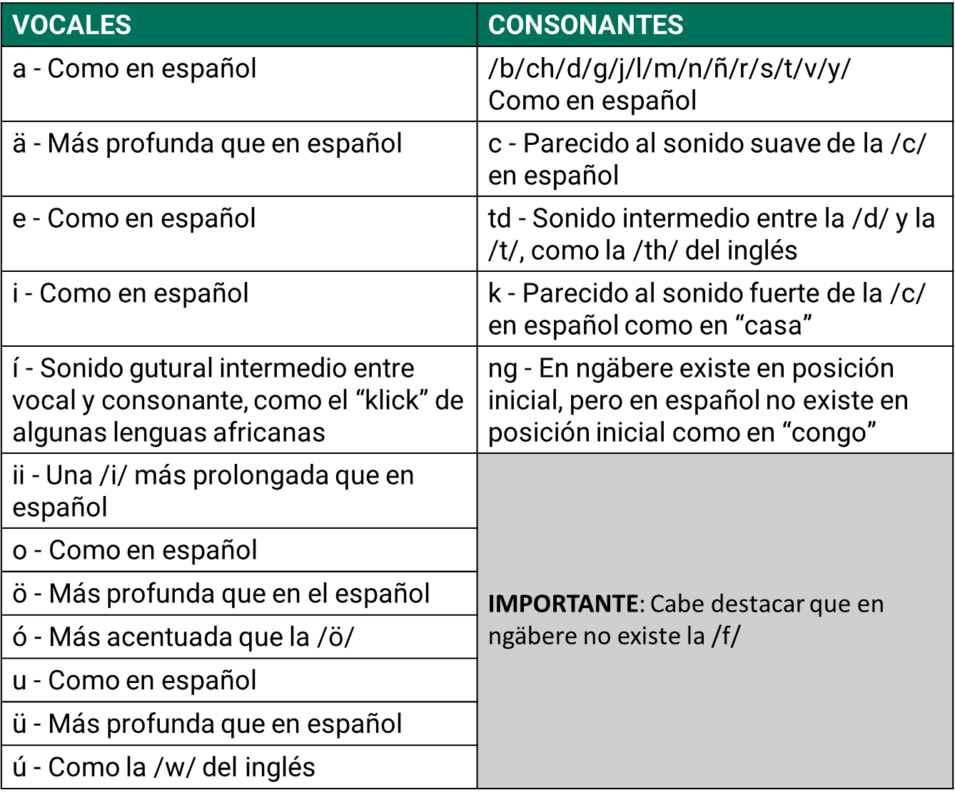

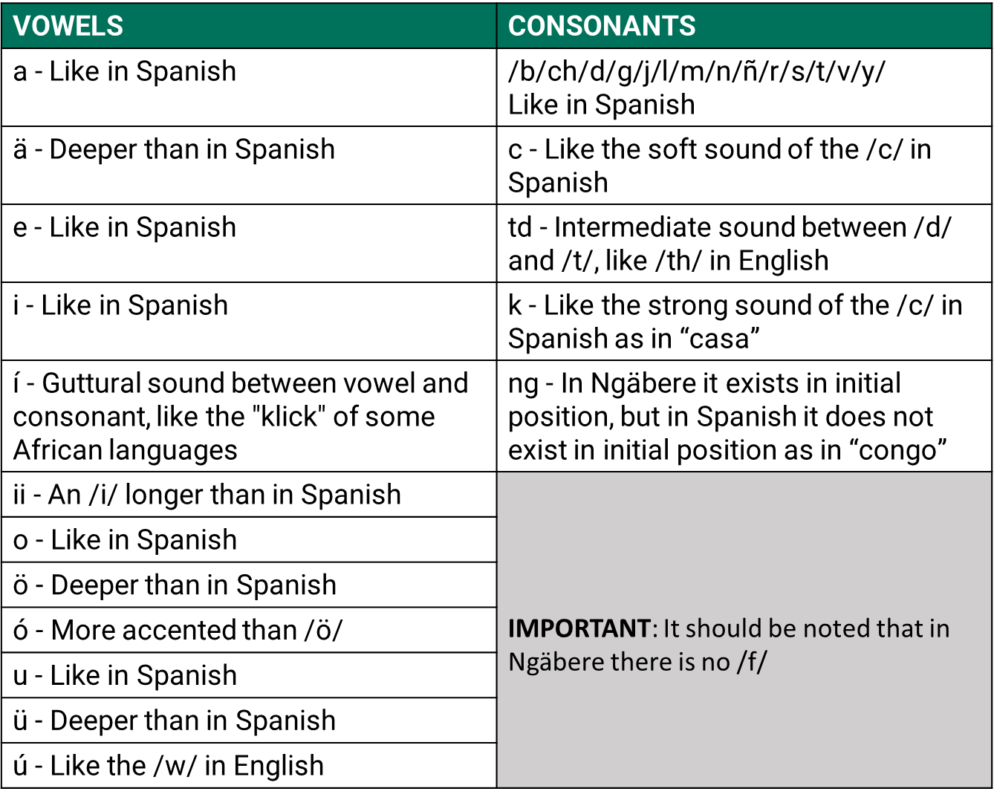

Para facilitar la lectura en ngäbere, hemos adaptado, con algunas modificaciones, el sistema en el breve diccionario ngäbere-español Kukwe Ngäbere de Melquiades Arosemena y Luciano Javilla, publicado en 1979 por la Dirección del Patrimonio Histórico del Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INAC), ahora Ministerio de Cultura, y el Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

También conviene aclarar que esta historia proviene de narradores residentes en el corregimiento de Potrero de Caña, antes distrito de Tole de la provincia de Chiriquí, ahora distrito de Müna de la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé, de donde es oriundo el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, el recopilador-escritor. Por consiguiente, la fonología corresponde a la variación dialectal o regional “Guaymí del Interior” (vertiente del Pacífico) y que difiere del “Guaymí de la Costa” (vertiente caribeña de la provincia de Bocas del Toro y del ahora distrito de Kusapin en la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) en la Gramática Guaymí de Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, publicada en 1980 por Fe y Alegría. Esta variante corresponde a la que Arosemena y Javilla denominan “Chiriquí” y que contrasta con las variantes caribeñas de Bocas del Toro y costa de Bocas.

Esta etnohistoria fue publicada en 1986 en Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere/Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Etnohistoria Guaymí), por la Asociación Panameña de Antropología, con el Convenio PN-079 de la Fundación Inter-Americana (FIA) gestionada por el Dr. Mac Chapin, Antropólogo, quien nos animó a que siguiéramos el ejemplo que él había sentado al recopilar el Pab-Igala: Historias de la Tradición Kuna, publicadas en 1970 por el Centro de Investigaciones Antropológicas de la Universidad de Panamá, bajo la dirección de la Dra. Reina Torres de Araúz.

Este libro representó la labor del Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, cuando era estudiante en su segundo año en el Centro de Enseñanza e Investigación Agropecuaria de Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad de Panamá (FCAUP), no solo de escribir en ngäbere las narraciones que había oído relatar a sus familiares en su comunidad, sino también su esfuerzo de traducirlas al español como persona bilingüe que es, al igual que otros indígenas en Panamá quienes se esfuerzan por recibir una educación formal.

Las etnohistorias fueron recopiladas, grabadas en casetes y escritas por el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo en 1983 y 1984.

Como Profesora-Investigadora de Antropología y Sociología Rural en el CEIACHI de la FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Antropóloga, Ph.D., animó a Roger, como uno de sus estudiantes, a escribir las historias, convencerlo y demostrarle que no explotaría ni abusaría de su trabajo, sino que se le reconocería su mérito. Por consiguiente, la antropóloga se limitó solamente a hacer algunas correcciones de forma y estilo en las traducciones al español sin alterar su contenido.

Animamos a estudiantes de los siete pueblos originarios en la República de Panamá, y a docentes en escuelas, colegios y universidades públicas y privadas en Panamá, a que escriban en sus propios lenguajes y traduzcan al español las etnohistorias y cantos que escuchan en sus familias y comunidades, como parte de su educación informal.

También animamos a lectores de estas etnohistorias en ngäbere, español e inglés, a que dibujen las escenas que más les gustaron, como hicieron en el 2002, estudiantes en un curso de Educación y Sociedad, orientado por la Dra. Joly, en la Facultad de Educación, Universidad Autónoma de Chiriquí.

Artículo 13 de la Declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas, aprobada por la Asamblea General, en su 107ª sesión plenaria el 13 de septiembre de 2007:

- Los pueblos indígenas tienen derecho a revitalizar, utilizar, fomentar y transmitir a las generaciones futuras sus historias, idiomas, tradiciones orales, filosofías, sistemas de escritura y literaturas, y a atribuir nombres a sus comunidades, lugares y personas, así como a mantenerlas.

- Los Estados adoptaran medidas eficaces para asegurar la protección de ese derecho y también para asegurar que los pueblos indígenas puedan entender y hacerse entender en las actuaciones políticas, jurídicas y administrativas, proporcionando para ello, cuando sea necesario, servicios de interpretación u otros medios adecuados.

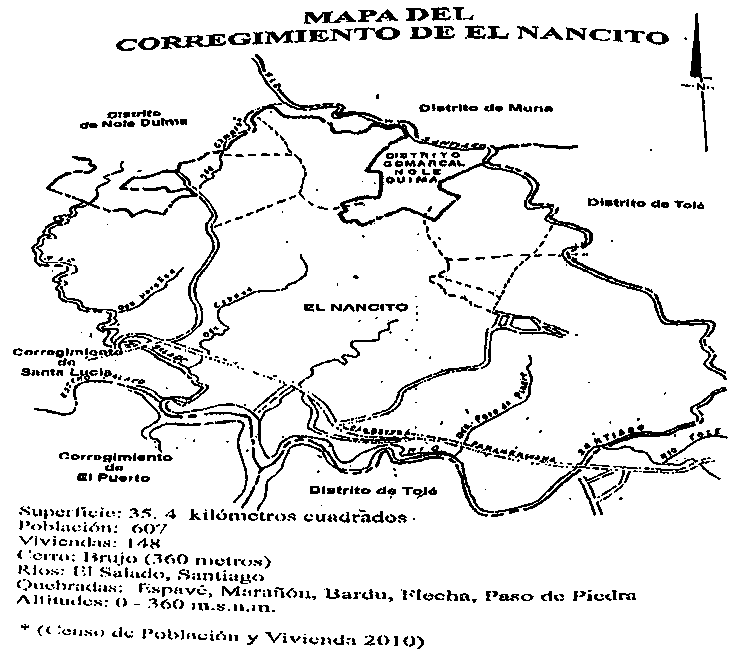

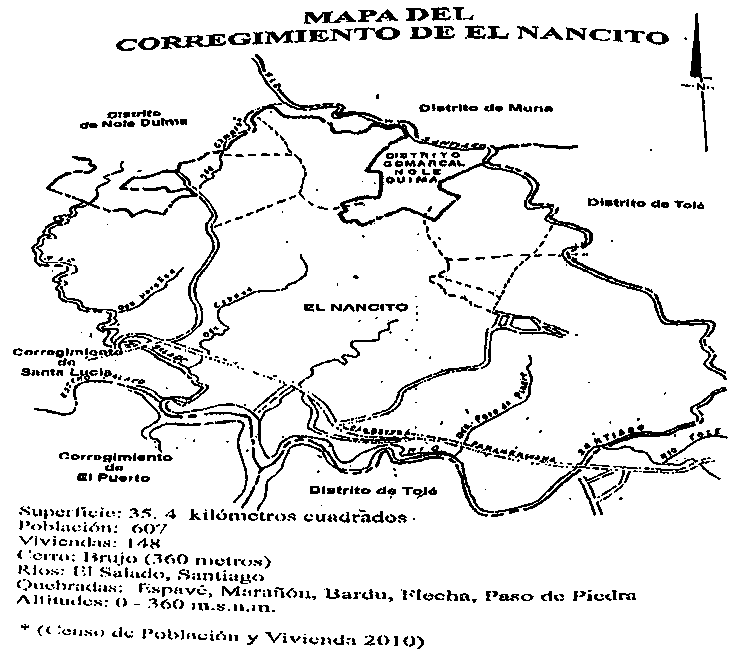

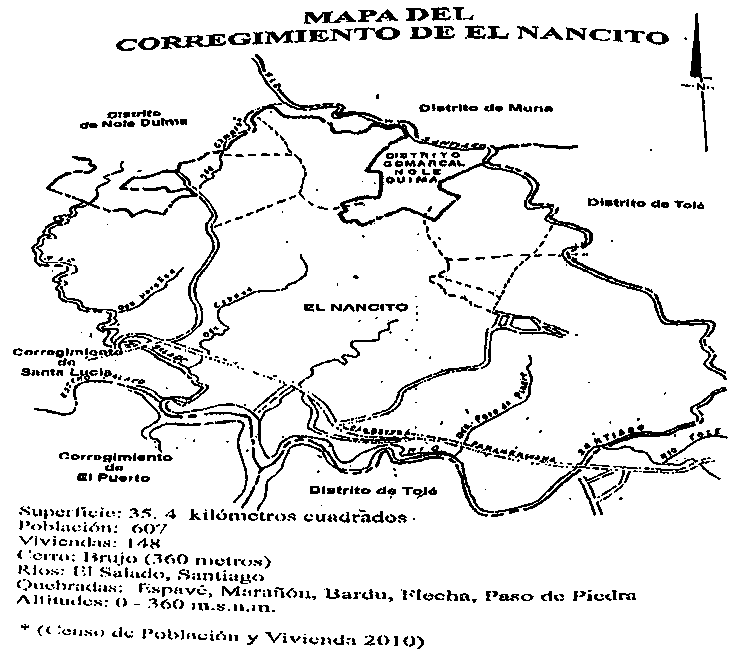

Una persona llamada Chico vivía por el hoy Potrero de Olla, distrito de Remedios (hoy Distrito Comarcal Nole Duima, segregado del corregimiento de El Nancito, del distrito de Remedios).

Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros Olimpia Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2011:36 | Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros Olimpia Remedios: Legendary Land. Panama: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2011:36.

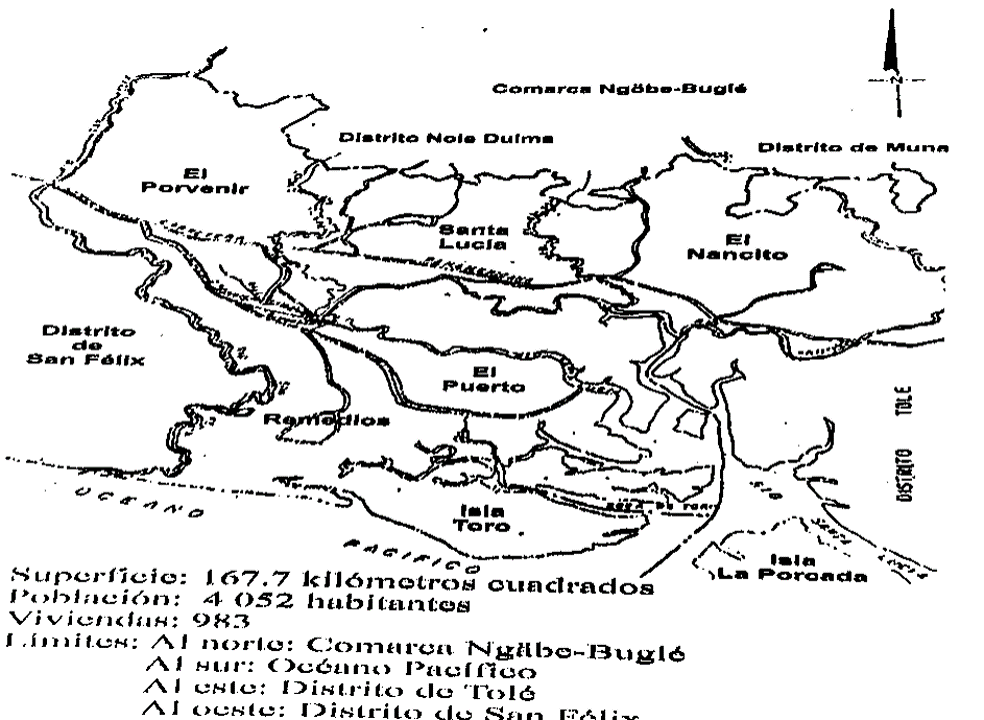

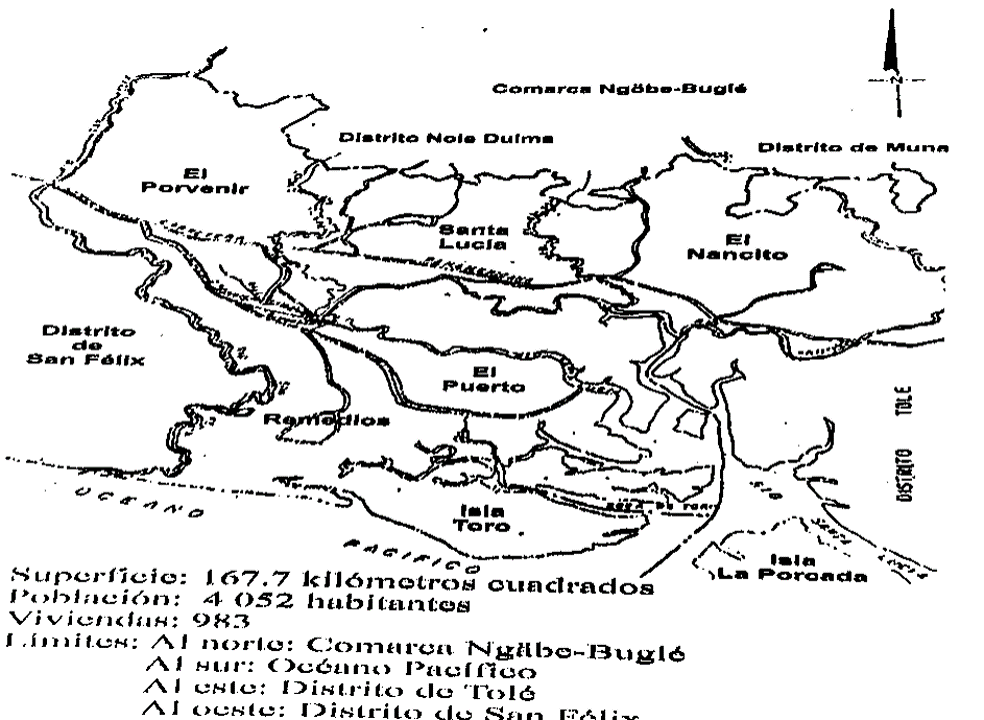

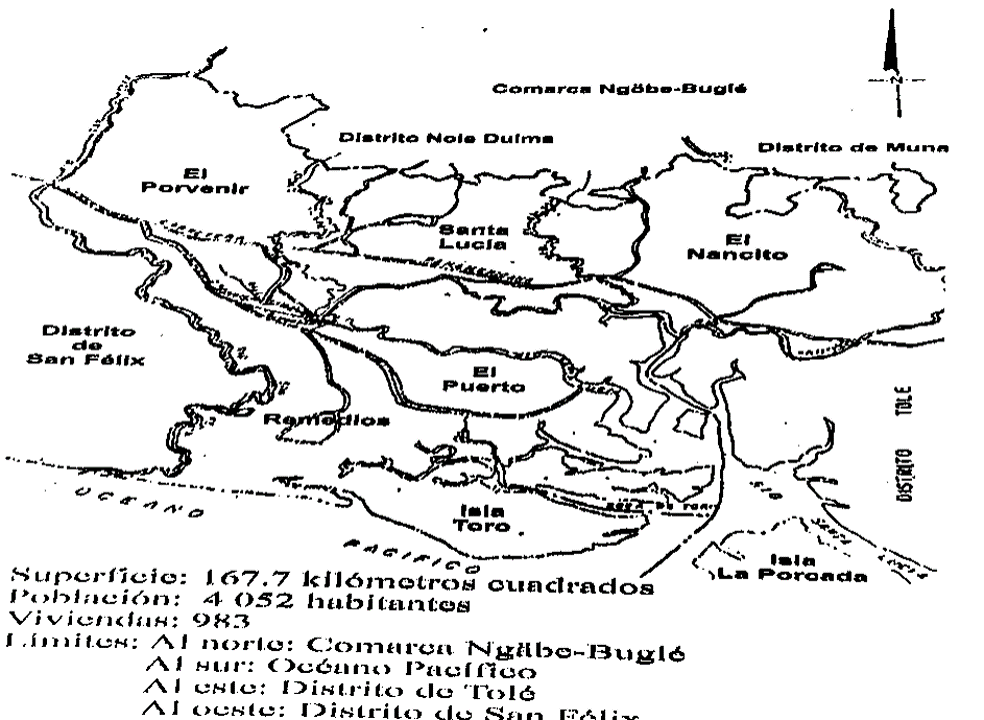

En el lado izquierdo del mapa del distrito de Remedios está el río San Félix que divide el distrito de San Félix del distrito de Remedios. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros Olimpia Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2011:34 | On the left side of the map of the district of Remedios is the river San Felix that divides de district of San Félix from the district of Remedios. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros Olimpia Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2011:34.

Este era un campesino pobre y mediocre quien trabajaba cuidando puercos para su patrón quien vivía en Remedios. Pero este campesino poseía inteligencia y capacidad, capaz de hacer cualquier hazaña que era desconocida completamente por las personas quienes lo rodeaban. Este campesino fue quien quemó las casas hace mucho tiempo en Remedios, se comenta.

El patrón lo tenía como esclavo trabajando, por lo cual, él se rebeló comiéndose los puercos del patrón a escondidas. Como hoy los ricos abusan y se valen de las gentes pobres, poniéndolos a trabajar fuertes y forzados para beneficios de ellos, así mismo ocurrió en aquel entonces, lo que motivó que sucediera este caso.

Chico, así se llamaba, quien quemó las casas de sus enemigos y después se tiró al mar en la desembocadura del río San Félix, se comenta desde hace mucho tiempo. Él estaba comiéndose los puercos; después iba a decirle al dueño, que se estaban perdiendo. Este era el mensaje que él siempre llevaba a su patrón; hasta que éste, motivado por el hecho, mandó a otra persona a cuidar los puercos con el campesino, para ver si era cierto que estaban desapareciendo los puercos, en qué forma y qué se hacían.

Lo que pasaba era que el mismo Chico estaba comiéndose los puercos, después iba a engañar al dueño, pegándole semejante mentira. Mataba el puerco; después guardaba su carne en un hueco que tenía hecho dentro de la casa, en el que él enterraba la carne para que nadie se diera cuenta y en la noche lo sacaba afuera.

Esa era la manera en que operaba su escondite y en esa operación lo encontró en la noche, sacando carne de puerco del hueco, el otro cuidador quien vino a investigar el caso. Inmediatamente, éste se fue y le dijo al dueño de los puercos lo que en realidad estaba ocurriendo.

El patrón entonces mandó a los comisarios a buscarlo para encarcelarlo cuando llegara. Los comisarios vinieron a buscarlo y se lo llevaron halado a caballo, con la intención de arrastrarlo por el suelo en el trayecto del camino hacia Remedios.

Le amarraron una soga, después lo ataron al caballo; así lo llevaron. Los comisarios, con la intención de arrastrarlo por el suelo, le pegaron al caballo y lo llevaron corriendo; pero, él también cogió impulso y se fue corriendo a la par del caballo. Los comisarios no pudieron arrastrarlo por el suelo en ese momento, y así fueron repitiendo cada vez que esto ocurría con él, para arrastrarlo, hasta llegar al incipiente pueblo de Remedios. Allí lo pusieron preso, pero él se escapaba de la cárcel en forma misteriosa.

Sus enemigos se cansaron de él, de cuidarlo en la cárcel y de sus artimañas, de no poder encerrarlo en la cárcel y que no se escapara. Entonces, le cogieron tanto odio, que querían desaparecerlo. Con esa intención, le preguntaron a él qué era lo que debían hacer para que se muriera, sin usar ningún tipo de armas como usaban los carceleros. Él contestó diciendo que le amarraran bastante paja seca, después poniéndole fuego, entonces él se moriría quemado. En esa forma respondió sin temor alguno a sus enemigos.

Los carceleros, ni cortos ni perezosos, queriendo quemarlo sin dejar transcurrir más tiempo, hicieron en perjuicio de Chico lo que él mismo dijo, tomando como verdadera la recomendación. Le amarraron bastante paja seca, después le pusieron fuego. Él, en vez de quemarse en la llama, salió muy tranquilo, corriendo, envuelto en llamas y por allí fue poniendo fuego a las casas que había por allí en ese momento. Puso todas las casas en fuego. Después, como el ruido de un extraordinario ciclón, se fue elevando en el cielo de Remedios y se fue, para caer en la desembocadura del Río San Félix en el mar.

Después de este suceso, nadie lo volvió a ver hasta el día de hoy. A los colonos sólo les quedó su amargo recuerdo por el incendio del pueblo de Remedios, que acabó con todos quienes había por allí en ese momento. Se fue para siempre.

Después de esto, hace mucho tiempo, cuando el mar rugía en la desembocadura del Río San Félix, entonces los indígenas que sí sabían quien era Chico, se ponían a decir: “Chico está bravo en la desembocadura del río San Félix. Esta vivo Chico, pero vive en el mar”. Se comenta eso desde su ida hasta ahora, por los narradores.

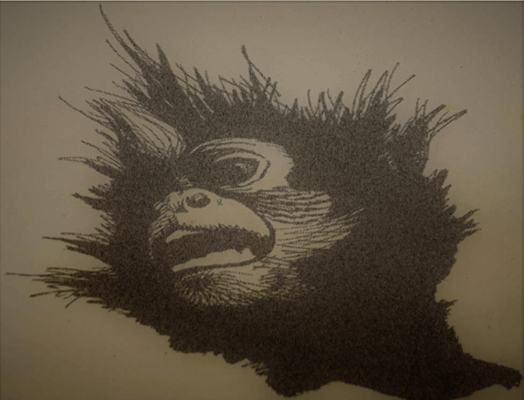

Dibujo del ingeniero agrónomo Arnold Troncoso de Chico lanzándose al mar en la desembocadura del río San Félix. | Drawing of Agricultura Engineer Arnold Troncoso of Chico throwing himself to the ocean at the mouth of the San Félix river.

Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011:50 | Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros. Remedies: Legendary Land. Panama: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2011: 50

Foreword

FOREWORD

To facilitate reading in Ngäbere, we have adapted, with some modifications, the system in the short Ngäbere-Spanish dictionary Kukwe Ngäbere by Melquiades Arosemena and Luciano Javilla, published in 1979 by the Directorate of Historical Heritage of the National Institute of Culture (INAC), now the Ministry of Culture, and the Summer Institute of Linguistics.

It should also be clarified that this story comes from narrators residing in the village of Potrero de Caña, formerly the Tole district of the Chiriquí province, now the Müna district of the Ngäbe Buglé region, from which the Agronomist Roger Séptimo, the compiler and writer is a native. Consequently, the phonology corresponds to the dialectal or regional variation "Guaymí del Interior" (Pacific slope) which differs from the "Guaymí de la Costa" (Caribbean slope of the province of Bocas del Toro and the now district of Kusapin in the Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) in the Guaymí Grammar of Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, published in 1980 by Fe y Alegría. This variant corresponds to what Arosemena and Javilla call "Chiriquí" and which contrasts with the Caribbean variants of Bocas del Toro and the coast of Bocas.

This ethnohistory was published in 1986 in Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere / Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Ethnohistory Guaymí), by the Panamanian Association of Anthropology, with the PN-079 Agreement of the Inter-American Foundation (FIA) managed by Dr. Mac Chapin, Anthropologist, who encouraged us to follow the example he had set by compiling Pab-Igala: Histories of the Kuna Tradition, published in 1970 by the Center for Anthropological Research of the University of Panama, under the direction of Dr. Reina Torres de Araúz.

This book represented the work of the Agricultural Engineer Roger Séptimo, when he was a student in his second year at the Center for Agricultural Teaching and Research in Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, University of Panama (FCAUP), not only writing in Ngäbere the stories that he had heard from his family members in his community, but also his effort to translate them into Spanish as a bilingual person that he is, like other indigenous people in Panama, who are striving to receive a formal education.

The ethnohistories were compiled, recorded on cassettes and written by the Agronomist Roger Séptimo in 1983 and 1984.

As Professor-Researcher of Anthropology and Rural Sociology at the CEIACHI of the FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Anthropologist, Ph.D., encouraged Roger, as one of her students, to write the stories, convince him and show him that she would not exploit or abuse his work, but that he would get credit. Consequently, the anthropologist limited herself only to making some corrections of form and style in the Spanish translations without altering their content.

We encourage students from the seven indigenous peoples in the Republic of Panama, and teachers in public and private schools, colleges and universities in Panama, to write in their own languages and translate the ethnohistories and songs they hear in their families and communities into Spanish, as part of their informal education.

We also encourage readers of these ethnohistories in Ngäbere, Spanish and English, to draw the scenes that they liked the most, as they did in 2002, students in an Education and Society course, directed by Dr. Joly, at the Faculty of Education, Autonomous University of Chiriquí.

Article 13 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, approved by the General Assembly, in its 107th plenary session on September 13, 2007:

- Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, promote and pass on to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to name and maintain their communities, places and people.

- The States shall adopt effective measures to ensure the protection of this right and also to ensure that indigenous peoples can understand and make themselves understood in political, legal and administrative actions, providing for this, when necessary, interpretation services or other appropriate means.

A person named Chico lived in what is now known as Potrero de Olla (now comarcal district of Nole Duima, segregated from the corregimiento of El Nancito). This was a poor and mediocre peasant who worked taking care of pigs for his master who lived in Remedios. But, this peasant possessed intelligence and capability, able to make any feat that was completely unknown to the persons around him. This peasant was who burned the houses in Remedios a long time ago, is commented.

His master had him working as a slave, for which Chico rebelled eating the pigs of his master in a secret manner. Like nowadays that the rich abuse and take advantage of poor people, forcefully putting them to do heavy tasks for the benefit of themselves, just the same it occurred at that time, and is what motivated this case.

Chico, so was called the one who burned the houses of his enemies and then threw himself in the mouth of the river San Felix, is commented since a long time ago.

Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros Olimpia Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2011:36 | Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros Olimpia Remedios: Legendary Land. Panama: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2011:36.

En el lado izquierdo del mapa del distrito de Remedios está el río San Félix que divide el distrito de San Félix del distrito de Remedios. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros Olimpia Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2011:34 | On the left side of the map of the district of Remedios is the river San Felix that divides de district of San Félix from the district of Remedios. Sánchez Pinzón, Milagros Olimpia Remedios: Tierra Legendaria. Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2011:34.

He was eating the pigs; and afterwards would go to tell the owner that the pigs were lost. This was the message that he always took to his master; until the latter, motivated by this fact, sent another person to take care of the pigs with the peasant, to see if it was true that the pigs were disappearing, in which way, and where they went.

What was happening was that Chico himself was eating the pigs, and then would go to fool the owner, telling him such a lie. He would kill a pig; then would store the meat in a hole that he had made inside his house, in which he buried the meat so that no one could become aware, and then would take it out at night.

That was the way in which he operated the hiding place and, in this operation, he was found one night, taking the pork meat out of the hole, by the other caretaker who went to investigate the case. Immediately, the latter went and told the owner of the pigs what was really occurring.

The master then sent the commissaries to get him and jail him when he arrived. The commissaries went to get him and took him being pulled by a horse, with the intention of dragging him on the ground on the road towards Remedios.

They tied him with a rope, then tied him to the horse; thus they took him. The commissaries, with the intention of dragging him on the ground, hit the horse and took it running; but, he also took impulse and went running alongside the horse. The commissaries could not drag him on the ground at that moment, and thus they repeated it each time that this occurred with him, to drag him, until arriving at the new town of Remedios. There they jailed him, but he escaped from the prison in a mysterious way.

His enemies got tired of him, of taking care of him in prison and of his cunningness, of not being able to keep him in prison without his escapes. Then they were so angry, that they wanted to disappear him. With that intention, they asked him what they should do so that he could die, without any type of arms as the jailors used. He answered that they should tie plenty dry leaves around him, then put fire, and then he would die burned. In this way he answered without any fear of his enemies.

The jailors, without any delay, wanting to burn him without letting too much time elapse, did what Chico said to do with him, taking his recommendation as true. They tied plenty dry straw around him, then they put fire on him. He, instead of burning in flames, calmly came out, running, engulfed in flames, and went around putting on fire the houses that were there at that moment. He put all the houses on fire. Then, with the sound of an extraordinary cyclone, he began elevating himself in the sky of Remedios and was gone, to fall in the ocean at the mouth of the San Felix River.

After this event, no one has seen him until these days. The colonizers only had the sour memory of the fire that burned the town of Remedios, that finished with all that was there at that moment. He was gone forever.

After that, since a long time ago, when the ocean roars at the mouth of the San Felix River, then the indigenous people who knew who was Chico, would say: “Chico is angry at the mouth of the San Felix river. Chico is alive but lives in the ocean.” This is commented, since his departure until nowadays, by the narrators.

Dibujo del ingeniero agrónomo Arnold Troncoso de Chico lanzándose al mar en la desembocadura del río San Félix. | Drawing of Agricultura Engineer Arnold Troncoso of Chico throwing himself to the ocean at the mouth of the San Félix river.

Ni gä krörö nomlen nünen Ungüentü ngrabre, ni nebra nguitegrä döguäi nguarabe nomlen stribire mütü nguibiare riba madagrä. Akua nguitegrä ne abogo töi ñó gare ñácara ribanga ye.

Nguitegrä ne kägüe ju kurinse meguera Remedios nie. Nomlen ja clavoire ribagüe sribire, kontdi nomlen mütü güete gore.

Matdare sulia ngüian bogänlen kriígri kotda ribangan mie sribire jai se krere kontdi kugüe nögalingä. Chico nie abogo güe ju kugualin ribangangän biti nangua müegäte kädrie meguera. Ñara tänlin mütü güete biti tänlin nebe niere mütü bogänye.

Mütü tänlin nente tänlin nebe niere käre ribaye. Ne abogo käre bata mütü bogängüe ni mada miri nguibiare, era bongälen mütü nomlen nente ya, nomlen jrainen abogo riba mada jualin nguibiare. Ne-amlen ñara tänlin mütü güete biti tänlin riba ngögue nguarabe.

Nomlen mütü güen biti nomlen grie ügue, kä nüalin dobote kue te nomlen grí doboimete abogo nomlen dengäta kuin dibire. Krere kontdi kualin mütü grie dengä kuin ribaye. Riba nigalinta kägüe niebareta mütü bogänye, kontdi monso juilín ie miadre güite gäre.

Ribanga nü töen, kä nigi ngüenan modäbata, jäguei tementda ngingrabre gäre. Kö guiti bata biti diri modäbata jänigui. Ribagüe modä metalin jatalin jä nigalin vetegä, ñara kägüe ja krialinte arato nigalin vetegä modä batá ribaye. Nin nabalin jägolin temen ribaye ngingrabre, ne krere nigalin nebe jutatde Remedios, kontdi miri mada güite. Akua ñara tänlin nguitie ta, bata ribanga güi nainte nguibiare, amlen ribanga mädä namanlin bata kägüe ngualintari ie nuendre amlen götare niebare ie. Ñara kägüe niebare migä nötare mägäi ere jabata biti oguäbügadregä amlen ja götadre niebare kue. Ribanga tö namanlin kuguainsei kägüe nuembare bogänlen bata. Migä mogälintde ere bata biti oguabügalingä ñara nigalin vetegä jiriäbe, nigalin ñüguä guetegä jubata niguen kä ngrabre temen. Ju oguäbügalingä jogrä kue biti nögalingä kuinta nigalimbe Müegäte nebiti töalintda ñagare mada biti kä nügue krörö ne.

Nigalin be käregäre. Nebiti meguera amlen mren ngö nomlen nebengä möta, Müegäte amlen ngäbe nomlen neve niere Chico nibi robom Müegäte nomlentre nebe niere. Tä nire akua tä nünen mrente nienri meguera abogo biti kä nügue ne.