Árbol en Arraiján, provincia de Panamá Oeste, en finca de la historiadora Mágister Marcela Camargo Ríos y roca tallada en jardín de la Pastelería Alemana en Boquete, provincia de Chiriquí. | Tree in Arraiján, province of Panamá Oeste, on the estate of the historian Mágister Marcela Camargo Ríos and carved rock in the garden of the German Pastry Shop in Boquete, province of Chiriquí.

Metobos convertidos en árboles y rocas por los Mironombos y los Cronombos. | Metobos converted into trees and rocks by the Mironombos and the Cronombos.

Prólogo

PRÓLOGO

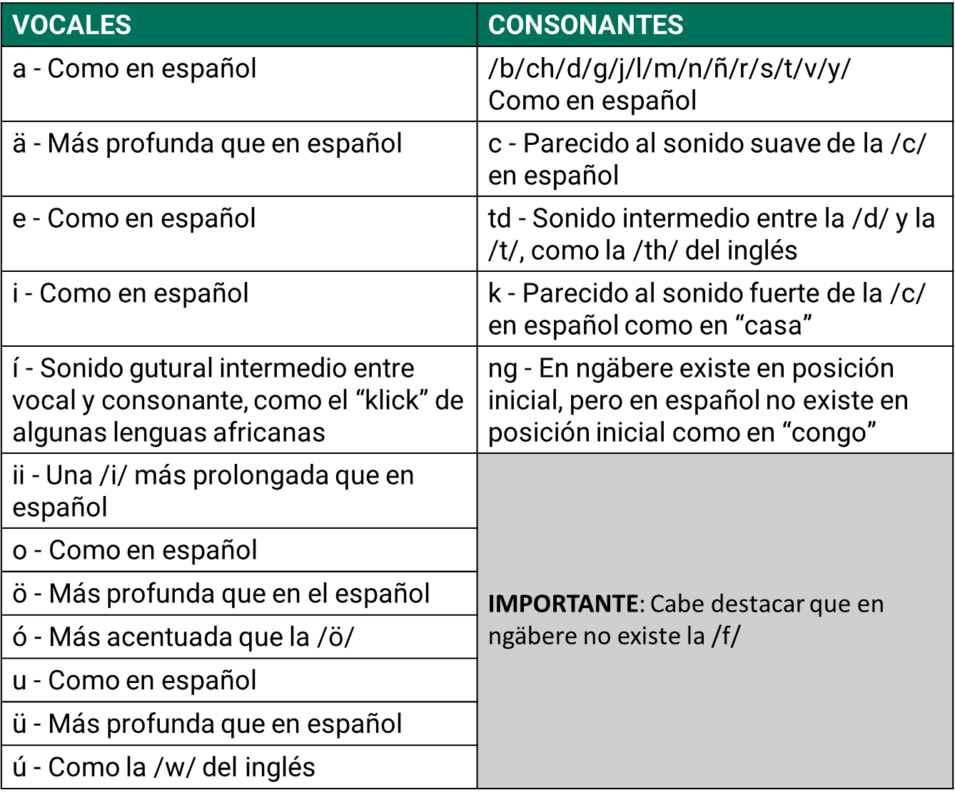

Para facilitar la lectura en ngäbere, hemos adaptado, con algunas modificaciones, el sistema en el breve diccionario ngäbere-español Kukwe Ngäbere de Melquiades Arosemena y Luciano Javilla, publicado en 1979 por la Dirección del Patrimonio Histórico del Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INAC), ahora Ministerio de Cultura, y el Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

También conviene aclarar que esta historia proviene de narradores residentes en el corregimiento de Potrero de Caña, antes distrito de Tole de la provincia de Chiriquí, ahora distrito de Müna de la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé, de donde es oriundo el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, el recopilador-escritor. Por consiguiente, la fonología corresponde a la variación dialectal o regional “Guaymí del Interior” (vertiente del Pacífico) y que difiere del “Guaymí de la Costa” (vertiente caribeña de la provincia de Bocas del Toro y del ahora distrito de Kusapin en la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) en la Gramática Guaymí de Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, publicada en 1980 por Fe y Alegría. Esta variante corresponde a la que Arosemena y Javilla denominan “Chiriquí” y que contrasta con las variantes caribeñas de Bocas del Toro y costa de Bocas.

Esta etnohistoria fue publicada en 1986 en Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere/Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Etnohistoria Guaymí), por la Asociación Panameña de Antropología, con el Convenio PN-079 de la Fundación Inter-Americana (FIA) gestionada por el Dr. Mac Chapin, Antropólogo, quien nos animó a que siguiéramos el ejemplo que él había sentado al recopilar el Pab-Igala: Historias de la Tradición Kuna, publicadas en 1970 por el Centro de Investigaciones Antropológicas de la Universidad de Panamá, bajo la dirección de la Dra. Reina Torres de Araúz.

Este libro representó la labor del Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, cuando era estudiante en su segundo año en el Centro de Enseñanza e Investigación Agropecuaria de Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad de Panamá (FCAUP), no solo de escribir en ngäbere las narraciones que había oído relatar a sus familiares en su comunidad, sino también su esfuerzo de traducirlas al español como persona bilingüe que es, al igual que otros indígenas en Panamá quienes se esfuerzan por recibir una educación formal.

Las etnohistorias fueron recopiladas, grabadas en casetes y escritas por el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo en 1983 y 1984.

Como Profesora-Investigadora de Antropología y Sociología Rural en el CEIACHI de la FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Antropóloga, Ph.D., animó a Roger, como uno de sus estudiantes, a escribir las historias, convencerlo y demostrarle que no explotaría ni abusaría de su trabajo, sino que se le reconocería su mérito. Por consiguiente, la antropóloga se limitó solamente a hacer algunas correcciones de forma y estilo en las traducciones al español sin alterar su contenido.

Animamos a estudiantes de los siete pueblos originarios en la República de Panamá, y a docentes en escuelas, colegios y universidades públicas y privadas en Panamá, a que escriban en sus propios lenguajes y traduzcan al español las etnohistorias y cantos que escuchan en sus familias y comunidades, como parte de su educación informal.

También animamos a lectores de estas etnohistorias en ngäbere, español e inglés, a que dibujen las escenas que más les gustaron, como hicieron en el 2002, estudiantes en un curso de Educación y Sociedad, orientado por la Dra. Joly, en la Facultad de Educación, Universidad Autónoma de Chiriquí.

Artículo 13 de la Declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas, aprobada por la Asamblea General, en su 107ª sesión plenaria el 13 de septiembre de 2007:

- Los pueblos indígenas tienen derecho a revitalizar, utilizar, fomentar y transmitir a las generaciones futuras sus historias, idiomas, tradiciones orales, filosofías, sistemas de escritura y literaturas, y a atribuir nombres a sus comunidades, lugares y personas, así como a mantenerlas.

- Los Estados adoptaran medidas eficaces para asegurar la protección de ese derecho y también para asegurar que los pueblos indígenas puedan entender y hacerse entender en las actuaciones políticas, jurídicas y administrativas, proporcionando para ello, cuando sea necesario, servicios de interpretación u otros medios adecuados.

Los Metobos contra los Mironombos y los Cronombos

Estos son los suguiás quienes mantenían una férrea lucha por dirimir sus poderes, para determinar el dominio de cada bando. La confrontación iba de encuentro personal a distancia mediante sucesos espectaculares, poco común vistos en la región. Mediante la narración se recuerda que nunca hubo tranquilidad en la región, sobre todo entre los suguiás quienes, supuestamente, tenían la misión de velar por sus gentes y darles la protección necesaria sembrando la paz y la tranquilidad entre sus habitantes. Siendo ellos, entonces, quienes protagonizaban las contiendas entre sí, cuando debían dar ejemplos de buena voluntad, hermandad, fraternidad e igualdad de oportunidad.

Parece que las contiendas eran producidas por querer establecer dominios egoístas, individualistas. Estos suguiás no querían tener competidores, por lo que trataban de aplastar a cualquier otro suguiá quien viniera a igualar su condición, o cualquier otro quien tratara de desplazarlo de su lugar. Estas contiendas iban al extremo que los bandos opuestos trataban de alguna forma de liquidar definitivamente a su contrario.

Así ocurría constante pugna por poder entre los bandos compuestos por los Metobos, como Ore Meto, Dego Meto, Rogara Meto y otros contra los bandos compuestos por los Mironombos y Cronombos.

Estas eran confrontaciones secretas y, a veces, ocultas que mantenían entre sí. Sus seguidores sólo conocían los resultados cuando ya habían terminado. En una de las tantas luchas a muerte, los Mironombos y Cronombos vencieron a los Metobos, volviéndolos en piedras que, según la narración, todavía se conservan como tal. En Lajero, distrito de Remedios, se encuentra una que dicen que es Ore Meto.

Se dice que él, cuando se iba para la cordillera, hacía la región atlántica de donde era originario y que vino a visitar a su hermano Rogara Meto quien vivía en Remedios, en su regreso se puso a descansar con su mujer y allí mismo se convirtió en piedra.

En su ubicación actual es un pedregón grande que tiene una piedra pequeña puesta encima y otra al lado que es de tamaño regular. Se dice que la piedra pequeña era hijo de Ore quien, en ese preciso momento lo llevaba en el hombro y se sentaron a descansar y allí están todavía sin mover desde hace buen rato.

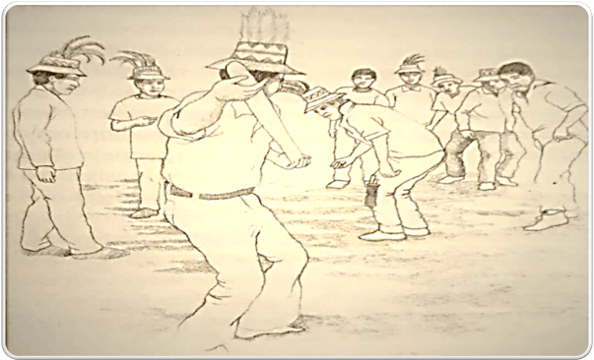

Dibujo de la obra ritual Krung Kita o Balsería. Guillermo Jiménez Miranda, En Pueblos Indígenas de Panamá: Hacedores de cultura y de historia. UNESCO-Panamá. 1998: 169-175 | Drawing of the ritual play Krung Kita or Balsería. Guillermo Jiménez Miranda, In Pueblos Indígenas de Panamá: Hacedores de cultura y de historia. UNESCO-Panamá. 1998:169-175

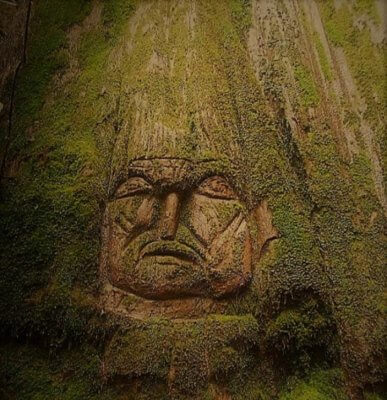

Lo mismo ocurrió a Dego Meto quien también lo volvieron como piedra, pero él está situado en la región montañosa de la zona atlántica comprendida en la actual provincia de Bocas del Toro. Se sabe esto gracias a los indígenas quienes iban a la balsería por la región de Bocas del Toro anualmente y que, por coincidencia tenían que pasar por donde estaba ubicado. Según los que veían, dicen que era una enorme piedra que estaba ubicada a la orilla de una quebrada y que tal piedra tenía nariz y ojos. Con confianza y certeza única, los indígenas decían que en la temporada lluviosa se veían en medio de sus ojos especies de guacamayas verdes.

Guacamaya verde (Ara militaris) es.wikipedia.org | Green Macaw (Ara militaris) en.wikipedia.org

Las piedras de Lajero no tienen ojos ni tampoco nariz; sólo son tres piedras de diferentes tamaños.

Otro hecho que se conoce sobre la piedra de Dego Meto, es que los indígenas quienes iban para la balsería, cuando llegaban donde está la piedra, se ponían a pintar la cara con colorete, como ellos se pintaban para la balsería, hasta que un día parece que no soportó más el trato y se disgustó, lanzando un enorme quejido, provocando espantos entre los indígenas, quienes entonces dejaron de pintarle la cara a la piedra.

Pinturas faciales para una Balsería. Sarsaneda Del Cid, J. NI NGÓBE TÓ BLITDE ÑO: Cómo hablan los ngóbe. Panamá: Acción

Ngóbe Cultural. Fotos de Héctor Endara Hill y Jorge Sarsaneda Del Cid, en portada y contraportada. 2009 | Facial paintings for a Balsería. Sarsaneda Del Cid, J. NI NGÓBE TÓ BLITDE ÑO: Cómo hablan los ngóbe. Panamá: Acción Cultural Ngóbe. Fotos of Héctor Endara Hill and Jorge Sarsaneda Del Cid, on front and back covers. 2009.

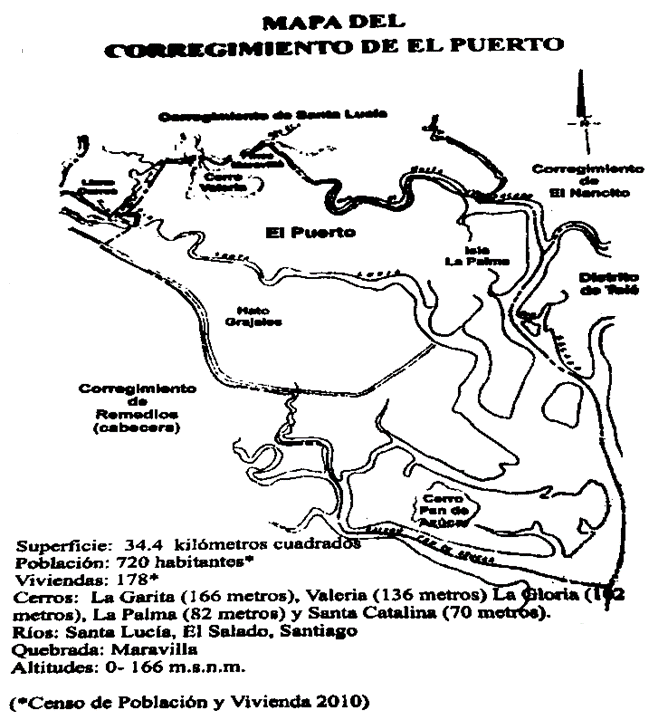

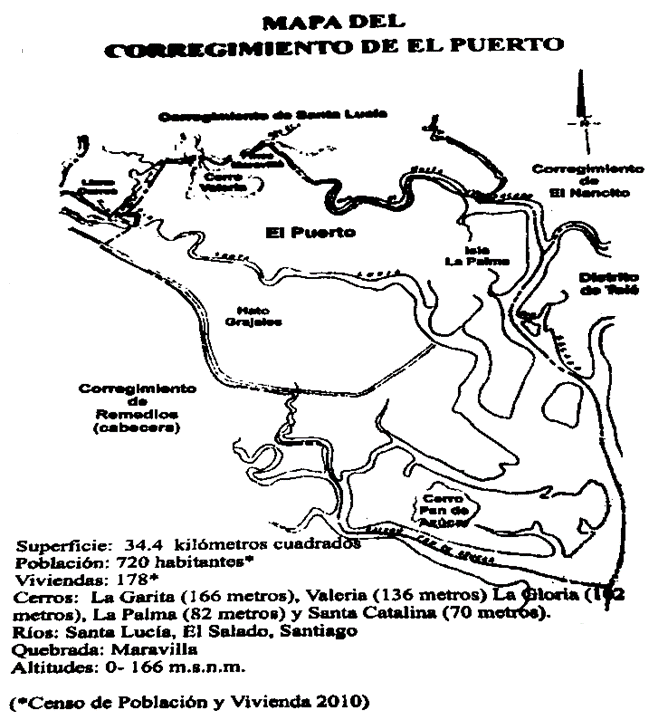

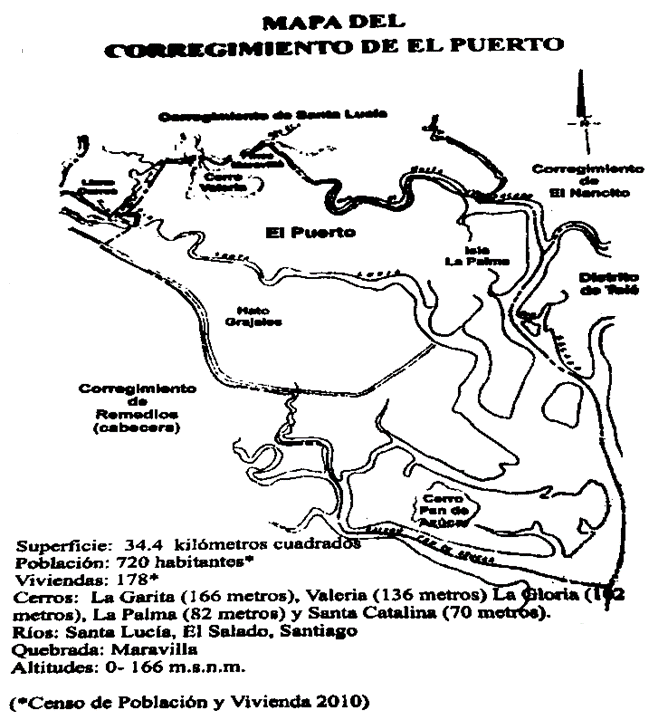

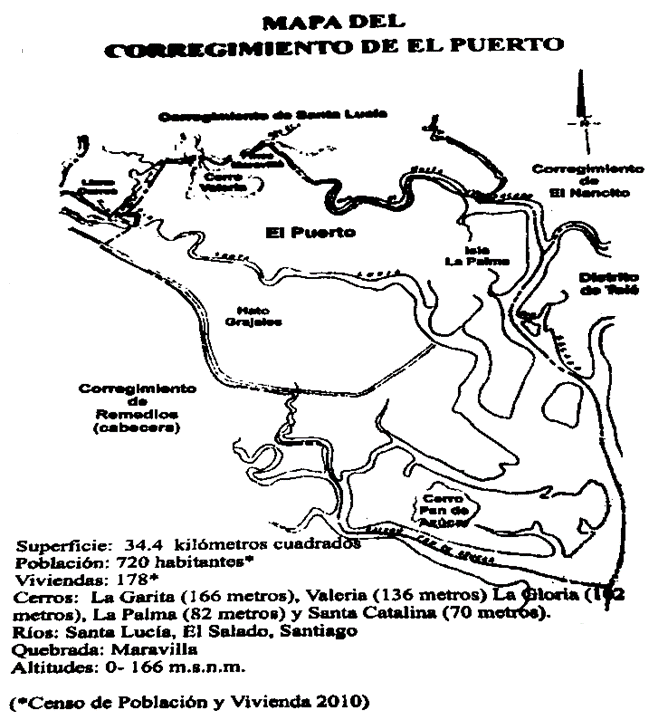

Actualmente, el cerro conocido como el Pan de Azúcar, ubicado a la orilla del mar Pacífico, cerca de la población de Remedios, lleva el nombre de Rogara Meto, conocido con el nombre de Rogatu, porque se piensa que era allí donde vivía antes de desaparecer.

Cerro Pan de Azúcar (Rogatu) Remedios:Tiera Lejendaria. p.40 Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, David, Chiriquí, Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2012 | Cerro Pan de Azúcar (Rogatu) Remedies: Tiera Lejendaria. p.40 Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, David, Chiriquí, Panama: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2012.

Cerro Rogatu: a la izquierda, desde el mirador de la vía a Nancito; a la derecha, del delta de Santa Lucía en Remedios. Fotos: Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, en Remedios: Tierra Legendaria, p. 77. David, Chiriquí, Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2012 | Rogatu hill: on the left, from the viewer balcony on the road to Nancito; on the right, from the Santa Lucia delta in Remedios. Fotos: Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, in Remedios:Tierra Lejendaria, p.77. David, Chiriquí, Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2012

Nota del Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo Jiménez

Los Mironombos, Cronombos y Metobos son grupos de suguiás quienes constantemente viven luchando unos contra otros. Estas luchas van de simples ofensas a contiendas frontales donde se pone en juego la vida y la existencia de ambos grupos, sin mediar alguna autoridad entre ellos. Sólo prevalece la ley del más fuerte, del más hábil y, sobre todo, del más capaz para realizar cualquier hazaña descomunal.

La contienda va encaminada a obtener el dominio absoluto y, por consiguiente, eliminar al contendor más débil. Los suguiás no se valen de armamentos guerreros como arcos y flechas para luchar uno contra otro. Tampoco se valen del pueblo para sus contiendas. Sólo se valen de sus poderes de clarividentes y de las naturalezas presentes para lograr su cometido.

La narración presenta a los Metobos humillando y subestimando la capacidad de los Mironombos y Cronombos. Éstos insisten en no ir a la contienda hasta que un día se les acaba la paciencia, se rebelan y vencen a los Metobos sin mayor dificultad. La derrota conlleva a que los Metobos sean vueltos como cualquier objeto inútil, para que nunca más vuelvan a luchar ni ser enemigos de consideración para los rivales. A esto se debe su conversión en árboles y piedras.

En la realidad, la práctica entre los suguiás siempre fue y ha sido hasta hace poco así. Por ello, cada narración destaca la misma contienda, pero con diferentes personajes y lugares.

Esto refleja que los verdaderos guiadores o líderes del pueblo guaymí (ngäbe) independientemente de que tuvieran la obligación de orientar, guiar y cuidar de su pueblo, tenían una pugna interna sin límite para decidir quién tenía mayor poder sin necesidad de alterar su función primaria de velar por el pueblo. Son gentes que aman a su pueblo y están dispuestos a combatir por su pueblo frente a los enemigos comunes, sin darles tregua. Pero, también viven crisis internas sin tregua, ya que para ellos quien decide dar tregua se da por vencido.

La lucha entre suguiás siempre ha sido de generación en generación, de una comunidad contra otra, de una región contra otra región, y, por ende, no tienen límite. La narración escrita no se puede interpretar como una lucha llevada a cabo en un día o en un año, sino que se refiere a una contienda que tomó varios años para decidirse. Por lo tanto, la narración generaliza y trata de recopilar un conglomerado de acontecimientos que guardan una similitud, destacándose solo un punto clave y concluyente en el transcurrir de los acontecimientos.

Árbol en Arraiján, provincia de Panamá Oeste, en finca de la historiadora Mágister Marcela Camargo Ríos y roca tallada en jardín de la Pastelería Alemana en Boquete, provincia de Chiriquí. | Tree in Arraiján, province of Panamá Oeste, on the estate of the historian Mágister Marcela Camargo Ríos and carved rock in the garden of the German Pastry Shop in Boquete, province of Chiriquí.

Metobos convertidos en árboles y rocas por los Mironombos y los Cronombos. | Metobos converted into trees and rocks by the Mironombos and the Cronombos.

Foreword

FOREWORD

To facilitate reading in Ngäbere, we have adapted, with some modifications, the system in the short Ngäbere-Spanish dictionary Kukwe Ngäbere by Melquiades Arosemena and Luciano Javilla, published in 1979 by the Directorate of Historical Heritage of the National Institute of Culture (INAC), now the Ministry of Culture, and the Summer Institute of Linguistics.

It should also be clarified that this story comes from narrators residing in the village of Potrero de Caña, formerly the Tole district of the Chiriquí province, now the Müna district of the Ngäbe Buglé region, from which the Agronomist Roger Séptimo, the compiler and writer is a native. Consequently, the phonology corresponds to the dialectal or regional variation "Guaymí del Interior" (Pacific slope) which differs from the "Guaymí de la Costa" (Caribbean slope of the province of Bocas del Toro and the now district of Kusapin in the Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) in the Guaymí Grammar of Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, published in 1980 by Fe y Alegría. This variant corresponds to what Arosemena and Javilla call "Chiriquí" and which contrasts with the Caribbean variants of Bocas del Toro and the coast of Bocas.

This ethnohistory was published in 1986 in Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere / Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Ethnohistory Guaymí), by the Panamanian Association of Anthropology, with the PN-079 Agreement of the Inter-American Foundation (FIA) managed by Dr. Mac Chapin, Anthropologist, who encouraged us to follow the example he had set by compiling Pab-Igala: Histories of the Kuna Tradition, published in 1970 by the Center for Anthropological Research of the University of Panama, under the direction of Dr. Reina Torres de Araúz.

This book represented the work of the Agricultural Engineer Roger Séptimo, when he was a student in his second year at the Center for Agricultural Teaching and Research in Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, University of Panama (FCAUP), not only writing in Ngäbere the stories that he had heard from his family members in his community, but also his effort to translate them into Spanish as a bilingual person that he is, like other indigenous people in Panama, who are striving to receive a formal education.

The ethnohistories were compiled, recorded on cassettes and written by the Agronomist Roger Séptimo in 1983 and 1984.

As Professor-Researcher of Anthropology and Rural Sociology at the CEIACHI of the FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Anthropologist, Ph.D., encouraged Roger, as one of her students, to write the stories, convince him and show him that she would not exploit or abuse his work, but that he would get credit. Consequently, the anthropologist limited herself only to making some corrections of form and style in the Spanish translations without altering their content.

We encourage students from the seven indigenous peoples in the Republic of Panama, and teachers in public and private schools, colleges and universities in Panama, to write in their own languages and translate the ethnohistories and songs they hear in their families and communities into Spanish, as part of their informal education.

We also encourage readers of these ethnohistories in Ngäbere, Spanish and English, to draw the scenes that they liked the most, as they did in 2002, students in an Education and Society course, directed by Dr. Joly, at the Faculty of Education, Autonomous University of Chiriquí.

Article 13 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, approved by the General Assembly, in its 107th plenary session on September 13, 2007:

- Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, promote and pass on to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to name and maintain their communities, places and people.

- The States shall adopt effective measures to ensure the protection of this right and also to ensure that indigenous peoples can understand and make themselves understood in political, legal and administrative actions, providing for this, when necessary, interpretation services or other appropriate means.

The Metobos against the Mironombos and the Cronombos

These were the suguiás who maintained a fierce conflict to measure their powers, to determine the dominion of each band. The confrontation was a personal encounter at a distance by means of spectacular events, uncommonly seen in the region. The narrative recalls that there never was tranquility in the region, above all, among suguiás who supposedly had the mission to look after their people and give them the necessary protection planting peace and tranquility among the inhabitants. Then, they themselves starred the conflicts among themselves, when they were those who should have given the example of good will, fraternity, and equal opportunity.

It seems that the conflicts were produced to establish selfish and individualistic dominions. These suguias did not want to have rivals, so they tried to crush any other suguiá who came to equal his condition or any other who tried to displace him. These conflicts would go to such extreme positions, so that the opposing bands would try somehow to definitely liquidate their opponents.

Thus there occurred a constant combat for power among the bands composed by the Metobos, such as Ore Meto, Dego Meto, Rogara Meto, and others against bands composed by the Mironombos and Cronombos.

These were secret confrontations and, sometimes, occult, that they had among themselves. Their followers only knew the results when they had finished the conflict. In one of the many conflicts to death, the Mironombos and Cronombos won the Metobos, transforming them into rocks that, according to the narrative, are still in that form. In Lajero, district of Remedios, there is one rock that is said it is Ore Meto.

It is said that, when he was going to the mountain ridge, towards the Atlantic region from where he was originally, and came to visit his brother Rogara Meto who lived in Remedios, on his return he stopped to rest with his wife and right there they were converted into rocks.

In that place there is a huge rock that has a smaller rock on top and to one side has another rock of regular size. It is said that the small rock was the son of Ore who at that moment was carrying the boy on his shoulder, and they sat down to rest, and they are still there without moving for a long time. The same occurred to Dego Meto who was also converted into a rock, but he is situated in a mountainous region in the Atlantic zone of what is now the province of Bocas del Toro. This is known thanks to the indigenous men who annually went to a balsería (contest with balsa sticks) in the Bocas del Toro region and, by coincidence, had to pass by this place.

Dibujo de la obra ritual Krung Kita o Balsería. Guillermo Jiménez Miranda, En Pueblos Indígenas de Panamá: Hacedores de cultura y de historia. UNESCO-Panamá. 1998: 169-175 | Drawing of the ritual play Krung Kita or Balsería. Guillermo Jiménez Miranda, In Pueblos Indígenas de Panamá: Hacedores de cultura y de historia. UNESCO-Panamá. 1998:169-175

According to those who saw it, they say that it is an enormous rock located on the bank of a stream, and that the rock has nose and eyes. With confidence and unique certainty, the indigenous men said that in the rainy season they could see in the middle of the green eyes’ macaws (Ara militaris).

Guacamaya verde (Ara militaris) es.wikipedia.org | Green Macaw (Ara militaris) en.wikipedia.org

The rock in Lajero has no eyes nor nose; there are only three rocks of different sizes.

Another fact that is known about the rock of Dego Meto, is that the indigenous men who would go to the balsería, when they got to where the rock was, they would paint the face of the rock with red designs, the same as they painted their faces for the balsería, until one day it seems that the rock could not stand anymore this treatment, and it yelled a loud moan, which scared the men, so then they stopped painting the face of the rock.

Pinturas faciales para una Balsería. Sarsaneda Del Cid, J. NI NGÓBE TÓ BLITDE ÑO: Cómo hablan los ngóbe. Panamá: Acción

Ngóbe Cultural. Fotos de Héctor Endara Hill y Jorge Sarsaneda Del Cid, en portada y contraportada. 2009 | Facial paintings for a Balsería. Sarsaneda Del Cid, J. NI NGÓBE TÓ BLITDE ÑO: Cómo hablan los ngóbe. Panamá: Acción Cultural Ngóbe. Fotos of Héctor Endara Hill and Jorge Sarsaneda Del Cid, on front and back covers. 2009.

Nowadays, the hill known as Pan de Azúcar*, located near the coast of the Pacific Ocean, near the town of Remedios, has the name of Rogara Meto, known by the toponym Rogatu, because it is thought that there was where he lived, before he disappeared.

*The raw sugar that is usually called panela in Panamá, used to be in a conical form, with a special knife to scrape the dark sugar, when the Spaniards introduced this sugarcane product from the Phillippines.

Cerro Pan de Azúcar (Rogatu) Remedios:Tiera Lejendaria. p.40 Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, David, Chiriquí, Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2012 | Cerro Pan de Azúcar (Rogatu) Remedies: Tiera Lejendaria. p.40 Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, David, Chiriquí, Panama: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2012.

Cerro Rogatu: a la izquierda, desde el mirador de la vía a Nancito; a la derecha, del delta de Santa Lucía en Remedios. Fotos: Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, en Remedios: Tierra Legendaria, p. 77. David, Chiriquí, Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2012 | Rogatu hill: on the left, from the viewer balcony on the road to Nancito; on the right, from the Santa Lucia delta in Remedios. Fotos: Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, in Remedios:Tierra Lejendaria, p.77. David, Chiriquí, Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2012

Note by Agricultural Engineer Roger Séptimo Jiménez

The Mironombos, Cronombos, and Metobos were groups of suguiás who constantly lived quarrelling with each other. These quarrels went from simple offenses to frontal battles that risked the life and existense of each group, without any authority to mediate between them. There only prevailed the law of the strongest, the most clever, and, above all, the most capable to do any extraordinary feat.

The contest sought to obtain absolute dominion and, consequently, eliminate the weakest. The suguiás did not use weapons like bows and arrows to fight against each other. They only used their powers as diviners and the natural environment present to achieve their endeavor.

This narrative presents the Metobos humiliated and subesteeming the capacity of the Mironombos and Cronombos. The latter insisted in not quarrelling, until one day they lost their patience, rebelled, and won the Metobos without major difficulty. The defeat involved that the Metobos were converted into any worthless object, so that they could never again fight nor be enemies of any consideration for their rivals. To this is due their conversión into trees and rocks.

In reality, this rivalry practiced by the suguiás always was and has been so until a few time ago. That is why each narrative presents the same struggle, but with different characters and places.

This reflects that the real guides or leaders of the guaymí (ngäbe) people, independently of the obligation that they had to orient, guide, and care for their people, they had an internal struggle without limits to decide who had the most power, without the necessity to alter their primary function to care for the welfare of their people. They were men who loved their people and were willing to fight for their people against their common enemies, without giving them any truce. But, also, they lived internal crisis without truce, as for them whoever decided to give a truce meant that he was giving up and had lost.

The fight among the suguiás has always been from generation to generation, of one community against another, of one region against another region, and, therefore, without limits. The narrative written cannot be interpreted as a struggle carried out in one day or in one year, but it refers to a contest that took several years to decide who won. On the other hand, the narrative generalizes and tries to gather a conglomerate of events that have similarities, distinguishing only a key and conclusive point in the development of the events.

Ngäbe ne abogo suguia kä nomlen ja gain käre, meden bäri töi kriígri abogo tö nomlen nebetre gain abogo bata ja gain suguiare röäre betre érebe kä nomlen kugüe nuenentre Jabata. Ja gaintre metre nguärere ere-nguanen abogo mentde temen kugüe noenentre jabata töibiti. Suguiare amlen töi kriígri aicete kä kälimen krägätre krägrä.

Ne abogo kädri käre, suguiare röärebe nomlentre ja gain abogobata nöbäi ñácara jabata, amlen rüre, ja gaintre käre. Suguia niguen ngäbe götäite temen ne abogo ngäbe nguibiagä, akua nomlen nebetre ja gain nguarabe, ja rüere abogo bata. Ne abogo nomlen migalin ngäbe nguibiagä, töi diangä, taintegä jabata, mäträgä ngäbe bata niguen temen abogo erere amatibe abogo rüre, ja gain käre niguen temen. Ne abogo kädrie meguera abogo biti kä nügue ne. Ne ñóbata amlen suguiare abogo tö nomlen nebe jamie kaibe abogo bata nomlentre nebe ja gain. Suguiare röäre ñan tö nomlen nebe ribanga mada töi suguiare, töi kriígri ñara krere abogo bata tö nomlen nebe gaigä, konti nomlentre nigüitetre jabata. Ngüitetre jabata abogo nomlentre ja gainre ñó erere nomlentre nuenen jabata abogo ribanga gadregä kuetre abogo bata töi nomlen nebetre, akua ne krere ñan nomlen nebe noembaretre ietre ere-nguanen. Ne krere abogo Metobo kägüe ja galintre Mironombo, Cronombo be tre.

Metobo suguiare Kriígri kädri ne-nguanen abogo Ore Meto, Dego Meto, Rogara Meto…nie, abogo kä nomlen rüretre, ja gaintre Mironombo, Cronombo be. Kugüe ne abogo noenentre kaibe jabata abogo ngäbe nguarabe gaintre, nomlen-ra niguen ta nguanre, meden nomlen mente abogo ga nomlen kuetre. Ne krere abogo Metobo nomlen ja gain Mironombo, Cronombo be konti Metobo nialinte mrä jabata Mironombo, Cronombo bentre. Kuitdalintre järe, ne abogo tä kälimen matare nieta, ne krere abogo kuitdalin iti merirebe, ngöbo ben ngöi Baguebata abogo tä kälimen, ne abogo Ore Meto, nieta.

Ne abogo nieta abogo ñara nigalinta jatöguäre griéguäre, ne amlen nomlen basare etebaye mren bata mötda temen, nigalinta jatöguäre, namanlin ja dügue jingrabre merirebe konti nigi ngüitalin järe nieta. Jä ne abogo tä kälimen, jä Oto krií abogo biti kuin chi kuáti, amlen ken arato abogo bä brai kuáti. Ne nieta abogo Ore Meto ngöbo, abogo nomlen ngüen katare ben namanlin tägälinte temen, ja dügue kontdi niguitalimen järe abogo kontdi tä kälimen matare. Ne krere nögalingä arato Dego Niron bata, kuitalin järe arato, akua abogo tä ngüitärä segri nieta. Ne abogo ngäbe nomlen nebe krünbata segri kä nomlen toen, abogo guebeite gare, jä ne abogo tä ñöbata nieta, ji guäräbata Mironte kä ne abogo kä mialin biti. Käi kontdita ngäbe nomlen nainta. Ngäbe nongä krünbata kä nomlen toen, abogo kä nomlen niere. Ne abogo jä krií ñö gräbata möta, jä abogo inzombiti amlen oguä arato ne kädrie nomlen krörö meguera. Ni gä Ngüite Biä ni krünguitagä. Ni gä Ngüite Biä ni krünguitagä krií nebe kare krünbata segrí kägüe toalin kä nomlen niere. Ne abogo kä nomlen niere arato abogo kä ñüre näire amlen Mörä nomlen nügue toen oguäte abogo toagä kä nomlen niere, ne abogo ñan kugüe nguarabe amlen era nieta ngäbegüe.

Ne amlen jä Baguebata abogo oguä, inzom ñagare, abogo jä be kömä. Ne abogo kädrie nomlen arato abogo ngäbe nongä krünbata kä nomlen Dego Niron järe migue käre diguebiti, jä miguetre krere nomlen nebetre jä miguetre krere nomlen nebetre jä oto migue arato, ne krere käre. Abogo krií diaro te bati ngäbe igalin krünbata namalin kontdi kä nigalin migue, nomlem migue jämen batibe kugüe namalingä krií krüguäte, kägüe namalingä krií krüguäte, kägüe migalintre ngonlienen amlen batibe ñan namanlin jä oto migjetre diguebiti. Ne abogo ngäbe nongä krünbata, nomlen nebetre segri ie gate, abogo kä nomlen kädriere. Matare abogo, mrenbata motda negri ngütio mren grabiti motda juta ngä Migabiti nguareta. Remedios ken suli ata käden Pan de Azúcar suliare abogo kä ngäbere Rogara Meto biti. Ngütio abogo kä dianta ngäbere Rogatü, abogo Rogara nomlen nünen ngüitio nebata biti kä mialin ngäbegüe, biti kä dianta matdare.

Dibujo de la obra ritual Krung Kita o Balsería. Guillermo Jiménez Miranda, En Pueblos Indígenas de Panamá: Hacedores de cultura y de historia. UNESCO-Panamá. 1998: 169-175 | Drawing of the ritual play Krung Kita or Balsería. Guillermo Jiménez Miranda, In Pueblos Indígenas de Panamá: Hacedores de cultura y de historia. UNESCO-Panamá. 1998:169-175

Guacamaya verde (Ara militaris) es.wikipedia.org | Green Macaw (Ara militaris) en.wikipedia.org

Pinturas faciales para una Balsería. Sarsaneda Del Cid, J. NI NGÓBE TÓ BLITDE ÑO: Cómo hablan los ngóbe. Panamá: Acción

Ngóbe Cultural. Fotos de Héctor Endara Hill y Jorge Sarsaneda Del Cid, en portada y contraportada. 2009 | Facial paintings for a Balsería. Sarsaneda Del Cid, J. NI NGÓBE TÓ BLITDE ÑO: Cómo hablan los ngóbe. Panamá: Acción Cultural Ngóbe. Fotos of Héctor Endara Hill and Jorge Sarsaneda Del Cid, on front and back covers. 2009.

Cerro Pan de Azúcar (Rogatu) Remedios:Tiera Lejendaria. p.40 Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, David, Chiriquí, Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2012 | Cerro Pan de Azúcar (Rogatu) Remedies: Tiera Lejendaria. p.40 Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, David, Chiriquí, Panama: Editorial Culturama Internacional. 2012.

Cerro Rogatu: a la izquierda, desde el mirador de la vía a Nancito; a la derecha, del delta de Santa Lucía en Remedios. Fotos: Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, en Remedios: Tierra Legendaria, p. 77. David, Chiriquí, Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2012 | Rogatu hill: on the left, from the viewer balcony on the road to Nancito; on the right, from the Santa Lucia delta in Remedios. Fotos: Milagros Sánchez Pinzón, in Remedios:Tierra Lejendaria, p.77. David, Chiriquí, Panamá: Editorial Culturama Internacional, 2012