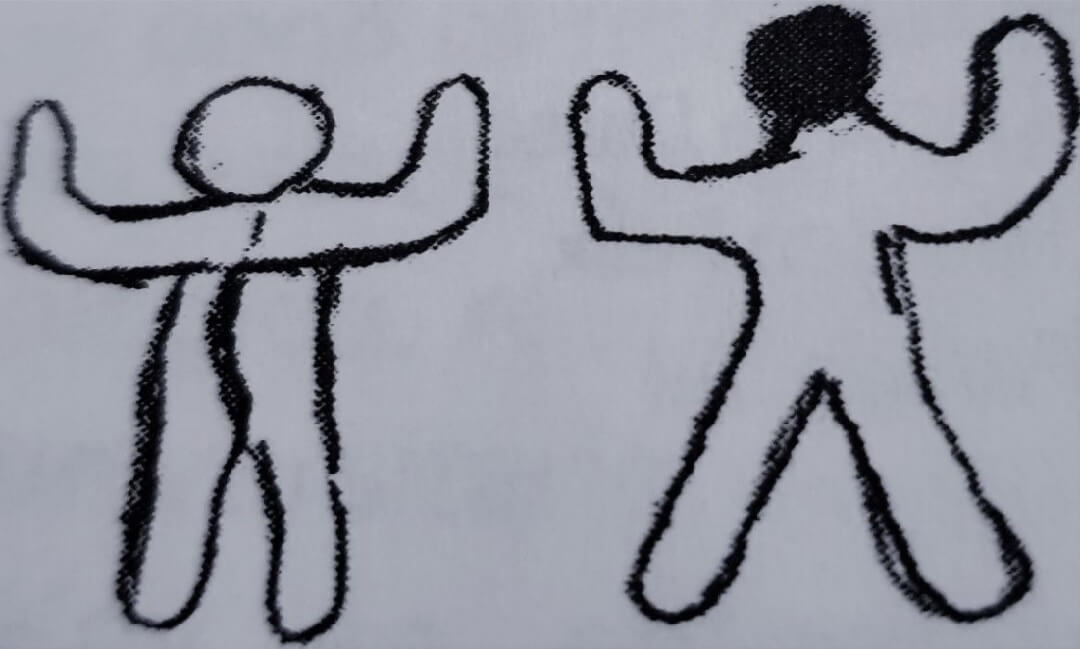

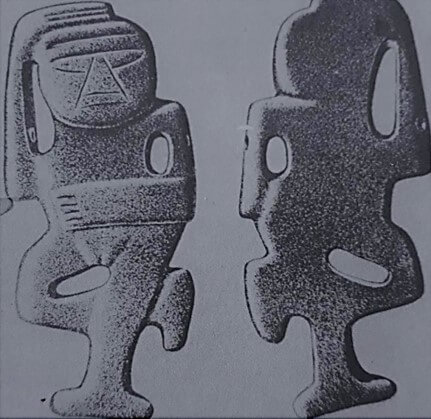

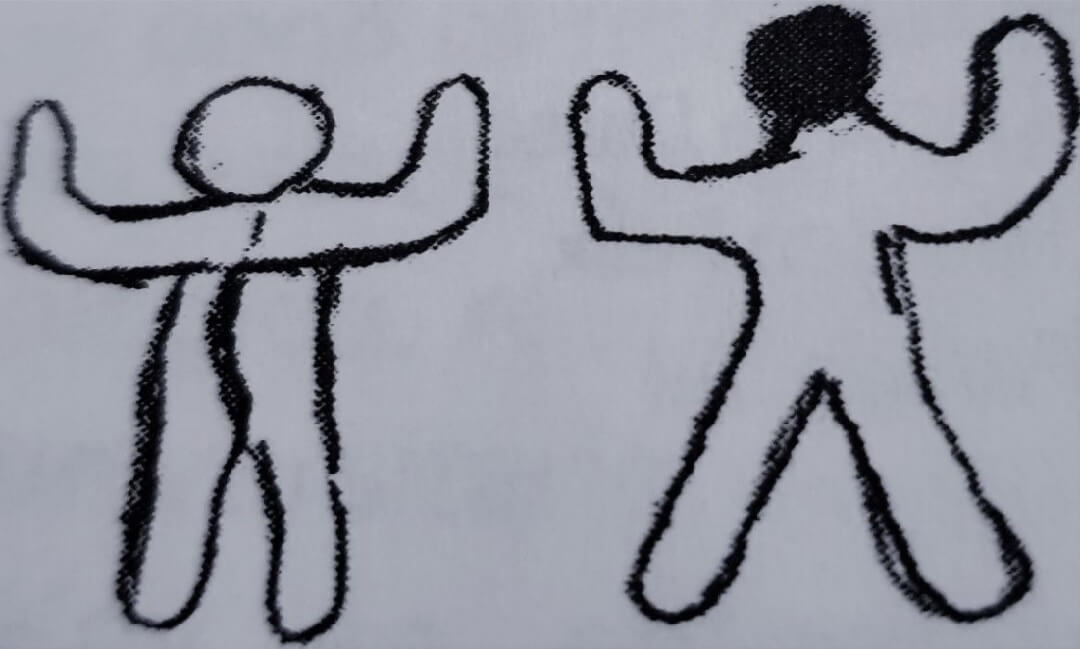

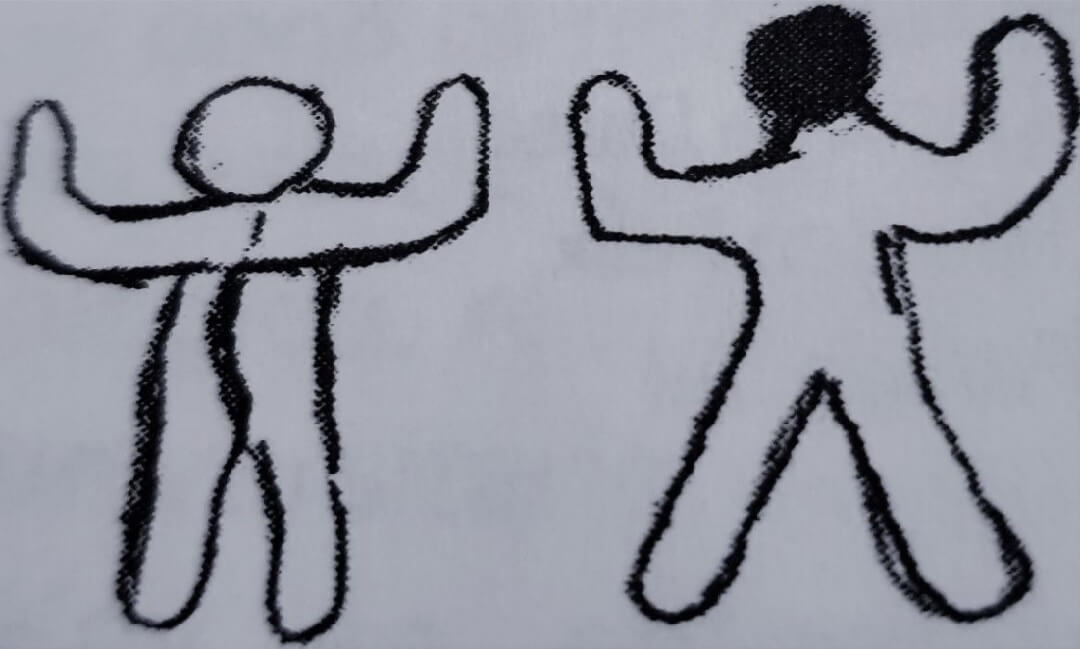

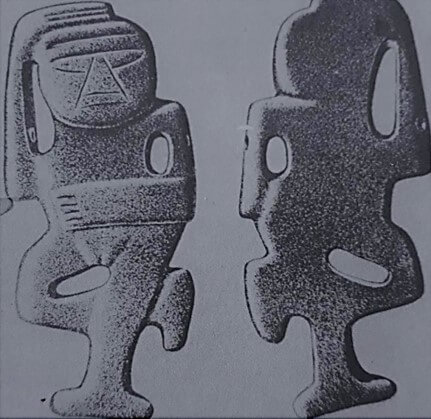

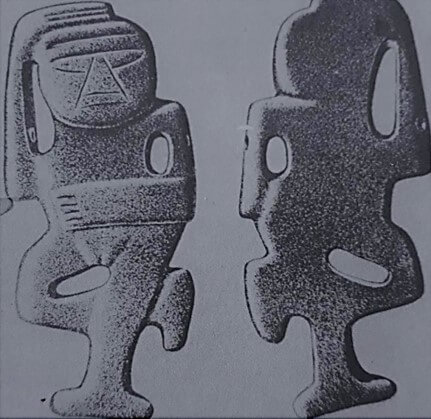

Dos figuras antropomorfas grabadas en petroglifo en Cuchilla de Bongo. En Conoce el Arte Rupestre en Panamá: Algunos Petroglifos en Chiriquí. Joly Adames, Luz Graciela, Compiladora, 2007:.28. David, Chiriquí, Panamá: Impresos Modernos | Two anthropomorphic figures engraved in a petroglyph at Cuchilla de Bongo. In Know the Rock Art in Panama: Some Petroglyphs in Chiriquí. Joly Adames, Luz Graciela, Compiler, 2007: .28. David, Chiriquí, Panama: Modern Impressions.

Prólogo

PRÓLOGO

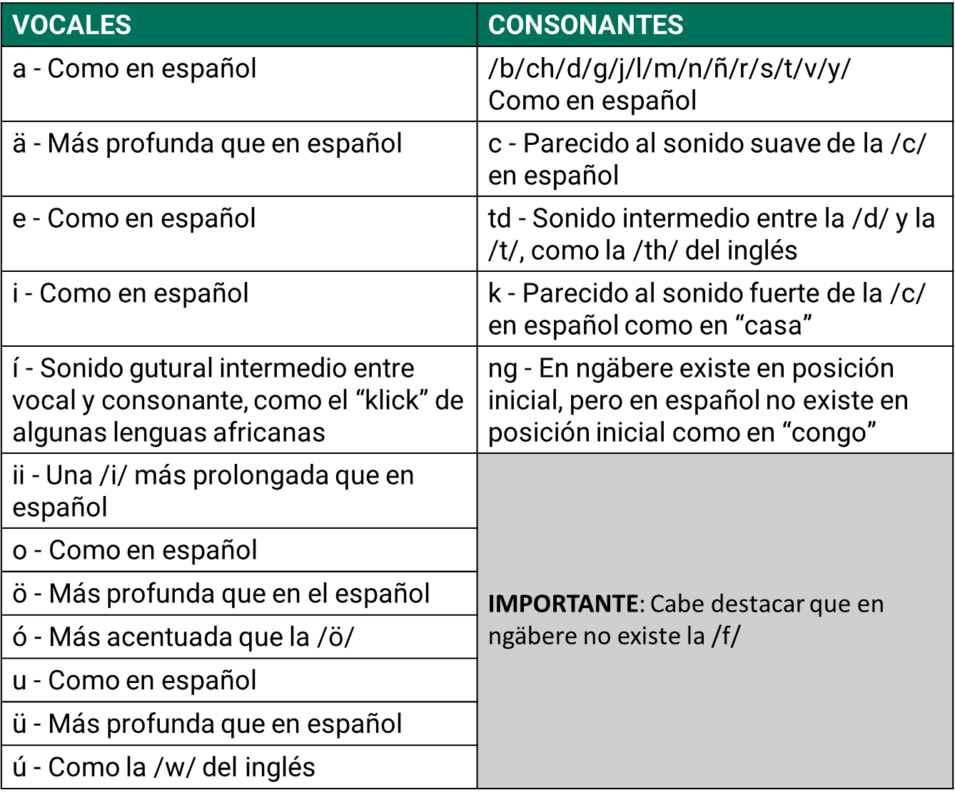

Para facilitar la lectura en ngäbere, hemos adaptado, con algunas modificaciones, el sistema en el breve diccionario ngäbere-español Kukwe Ngäbere de Melquiades Arosemena y Luciano Javilla, publicado en 1979 por la Dirección del Patrimonio Histórico del Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INAC), ahora Ministerio de Cultura, y el Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

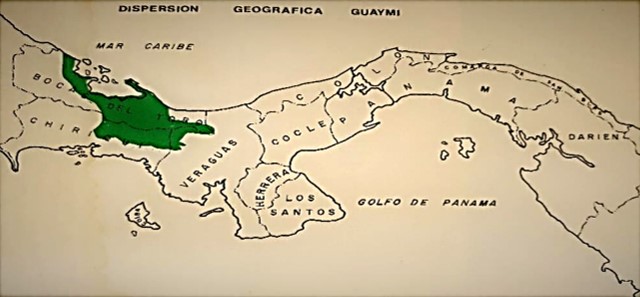

También conviene aclarar que esta historia proviene de narradores residentes en el corregimiento de Potrero de Caña, antes distrito de Tole de la provincia de Chiriquí, ahora distrito de Müna de la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé, de donde es oriundo el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, el recopilador-escritor. Por consiguiente, la fonología corresponde a la variación dialectal o regional “Guaymí del Interior” (vertiente del Pacífico) y que difiere del “Guaymí de la Costa” (vertiente caribeña de la provincia de Bocas del Toro y del ahora distrito de Kusapin en la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) en la Gramática Guaymí de Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, publicada en 1980 por Fe y Alegría. Esta variante corresponde a la que Arosemena y Javilla denominan “Chiriquí” y que contrasta con las variantes caribeñas de Bocas del Toro y costa de Bocas.

Esta etnohistoria fue publicada en 1986 en Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere/Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Etnohistoria Guaymí), por la Asociación Panameña de Antropología, con el Convenio PN-079 de la Fundación Inter-Americana (FIA) gestionada por el Dr. Mac Chapin, Antropólogo, quien nos animó a que siguiéramos el ejemplo que él había sentado al recopilar el Pab-Igala: Historias de la Tradición Kuna, publicadas en 1970 por el Centro de Investigaciones Antropológicas de la Universidad de Panamá, bajo la dirección de la Dra. Reina Torres de Araúz.

Este libro representó la labor del Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, cuando era estudiante en su segundo año en el Centro de Enseñanza e Investigación Agropecuaria de Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad de Panamá (FCAUP), no solo de escribir en ngäbere las narraciones que había oído relatar a sus familiares en su comunidad, sino también su esfuerzo de traducirlas al español como persona bilingüe que es, al igual que otros indígenas en Panamá quienes se esfuerzan por recibir una educación formal.

Las etnohistorias fueron recopiladas, grabadas en casetes y escritas por el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo en 1983 y 1984.

Como Profesora-Investigadora de Antropología y Sociología Rural en el CEIACHI de la FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Antropóloga, Ph.D., animó a Roger, como uno de sus estudiantes, a escribir las historias, convencerlo y demostrarle que no explotaría ni abusaría de su trabajo, sino que se le reconocería su mérito. Por consiguiente, la antropóloga se limitó solamente a hacer algunas correcciones de forma y estilo en las traducciones al español sin alterar su contenido.

Animamos a estudiantes de los siete pueblos originarios en la República de Panamá, y a docentes en escuelas, colegios y universidades públicas y privadas en Panamá, a que escriban en sus propios lenguajes y traduzcan al español las etnohistorias y cantos que escuchan en sus familias y comunidades, como parte de su educación informal.

También animamos a lectores de estas etnohistorias en ngäbere, español e inglés, a que dibujen las escenas que más les gustaron, como hicieron en el 2002, estudiantes en un curso de Educación y Sociedad, orientado por la Dra. Joly, en la Facultad de Educación, Universidad Autónoma de Chiriquí.

Artículo 13 de la Declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas, aprobada por la Asamblea General, en su 107ª sesión plenaria el 13 de septiembre de 2007:

- Los pueblos indígenas tienen derecho a revitalizar, utilizar, fomentar y transmitir a las generaciones futuras sus historias, idiomas, tradiciones orales, filosofías, sistemas de escritura y literaturas, y a atribuir nombres a sus comunidades, lugares y personas, así como a mantenerlas.

- Los Estados adoptaran medidas eficaces para asegurar la protección de ese derecho y también para asegurar que los pueblos indígenas puedan entender y hacerse entender en las actuaciones políticas, jurídicas y administrativas, proporcionando para ello, cuando sea necesario, servicios de interpretación u otros medios adecuados.

REY MONTEZUMA CONTRA MARCO CONCEPCIÓN

Rey Montezuma (1), así se llamaba un suguiá quien vivía por la serranía de San Félix. Lamentablemente, no sabemos con certeza en los años en que vivió. Era un suguiá muy poderoso, jefe de los Montezumas de San Félix.

Este suguiá culminó su vida en una contienda que tuvo con otro suguiá llamado Marco Concepción. No se sabe mucha cosa del Rey Montezuma en cuanto a su vida como suguiá, ni tampoco se conoce cuáles fueron las luchas que realizó frente a los colonizadores. Lo que más se ha recordado a través de los tiempos es su encuentro con el suguiá Concepción, para dirimir por la capacidad y el poder de los dos.

El suguiá Concepción vivía al otro lado del río Viguí, límite con la provincia de Veraguas, por la cercanía del lugar conocido hoy como Cerro Pelado o como La Palma. Todavía contamos en la actualidad con sus descendientes, que aún viven en el mismo lugar.

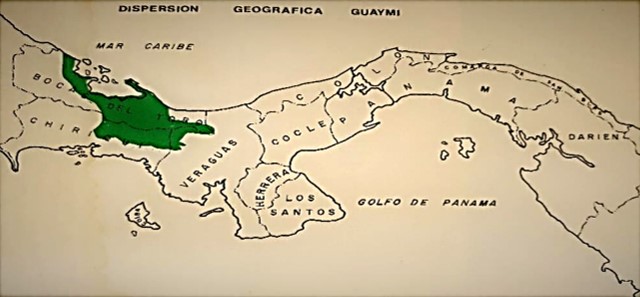

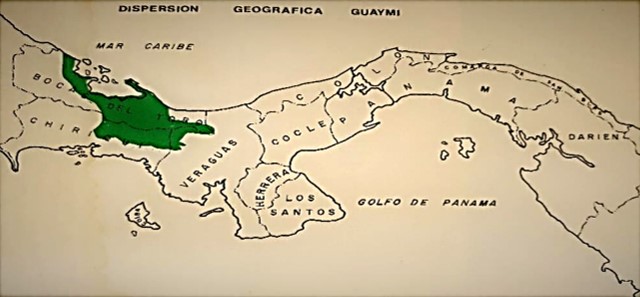

Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980:216 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 216 INDIGENOUS PANAMA. Panama: National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage.

Ahora pasamos a narrar lo que sucedió y por qué tuvieron que llegar a este extremo de rivalizar su poder, siendo los dos indígenas y Guaymíes (Ngäbe), sobre todo. Por otro lado, teniendo enemigos externos, debieron haberlos combatido juntos y no provocar una pugna interna entre los dos.

Resulta que entre los Guaymíes (Ngäbe) hubo muchos suguiás con poderes extraordinarios para proteger a sus pueblos y que en conjunto velaban por sus conciudadanos. Todos ellos tenían números plurales de sus seguidores, que eran libres para optar por ir a hacer consultas a cualquier suguiá que consideraran oportuno. Por lo que existían Guaymíes (Ngäbe) que iban donde varios suguiás voluntariamente; o bien, eran recomendados por los mismos suguiás para aunar esfuerzos en común.

En tales circunstancias, los Guaymíes (Ngäbe) viajaban lejos donde hubieran suguiás de gran renombre. Así ocurría que, por los lados de San Félix, iban muchos indígenas a hacer consulta y buscar protección de los males donde el suguiá Marco Concepción. Como es tradición, los suguiás siempre autorizan la ceremonia religiosa de la vigilia para ahuyentar a los males. Para tal caso, los Guaymíes (Ngäbe) que van donde suguiás siempre llevan cacao para que les haga efectiva su vigilia.

Así ocurría, iban bastantes indígenas donde el suguiá Concepción procedentes de San Félix. Eran familias vecinas que se agrupaban y acudían donde el mencionado suguiá periódicamente. Casi todos traían cacao para que se les dieran órdenes para sus vigilias. Estos hechos fueron los que un día provocaron la contienda entre los dos suguiás. Según la narración indígena, ocurrió de la siguiente manera.

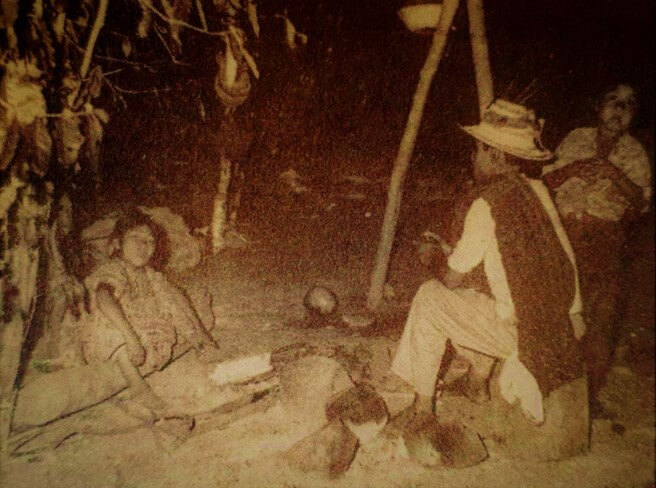

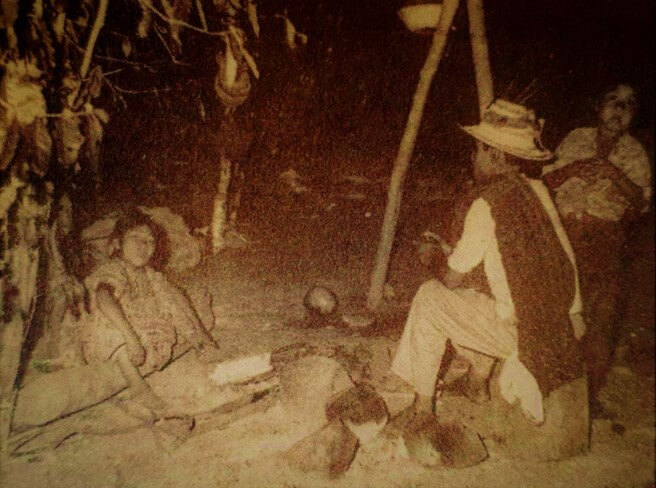

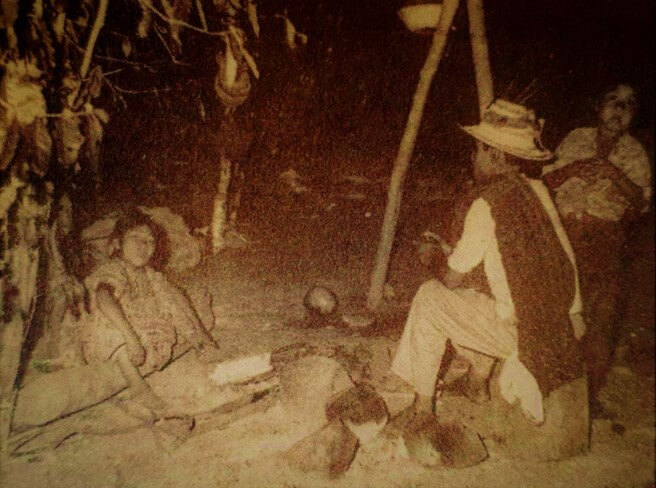

Beber cacao durante un velatorio, en Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 251. Panamá Indígena. Panamá, Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Drinking cocoa during a wake, In Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 251. Indigenous Panama. Panama, National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage.

Como era siempre de costumbre, llegó donde el suguiá Concepción un grupo bastante considerable de los indígenas Guaymíes (Ngäbe) procedentes de la cordillera de San Félix, a consultar con el suguiá y al mismo tiempo que se les diera la orden de realizar la vigilia. Resulta que antes se acostumbraba a guardar dieta cuando entraba a regir el primer día de la vigilia, que duraba alrededor de cinco días cada vigilia. La dieta que se guardaba era no comer sal, no tomar chicha, ni comer cosa asada al fuego. Actualmente, muy poco o nada se guarda de esta dieta. Cuando se le daba el visto bueno para realizar la vigilia a varias 14 personas a la vez, era norma que, terminada la primera vigilia, se iniciaba la segunda y, así, sucesivamente hasta terminar con la última, según la orden que iba dando el suguiá a cada persona. Significaba que, mientras no se terminara la última vigilia, no se podía romper con la dieta acostumbrada.

Estos grupos de indígenas, con el transcurrir de los días de la vigilia, ya no soportaban guardar la dieta. Como eran bastante las familias que celebraban la vigilia, una tras la otra, éstas llevaban meses sin poder comer la sal, tomar chicha, ni comer cosa asada.

Estos grupos querían romper con la dieta, ya que no resistían más comer las cosas sin el condimento de la sal. Se dieron en la tarea de conversar unos a los otros, diciendo por qué no se intentaba comer sal. Se argumentaba de que el suguiá estaba viviendo lejos de donde vivían ellos y que, por lo tanto, no era posible que se diera cuenta de lo mismo. Decían algunos: “No creo que se dé cuenta, él vive lejos de aquí; además, hay muchos cerros que dificultan las miradas de allá hasta acá y no es posible que ese suguiá pueda ver o darse cuenta de que rompamos con la dieta”. No quedando conformes con la teoría, quisieron llevar a cabo su deseo en la práctica.

Con esa idea, uno de ellos, en la comida que estaban cocinando, tiró un poco de sal. En el instante que hizo la sal contacto con la comida que se estaba cocinando, ésta se volvió toda cenizas. De esta manera comprobaron que no lo podían hacer. No importaba la distancia a que estuviera el suguiá, esto era imposible, ya que de alguna manera se hacía presente donde se realizaba la vigilia. De esa forma vieron reducido a nada su deseo de romper con la dieta.

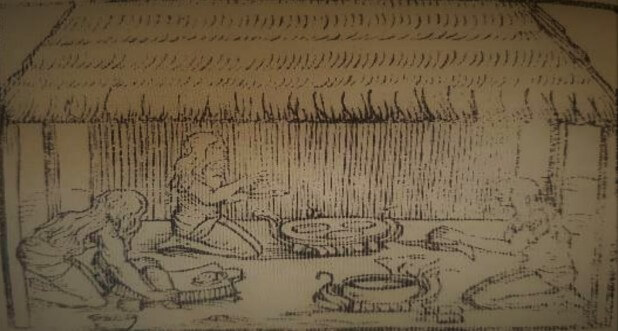

Lámina del libro de Girolano Benzoni que muestra las actividades domésticas indígenas. En Torres de Arauz, R. 1980: 56 Panamá Indígena. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico. Benzoni, G. “La Historia del Mundo Nuevo”. Biblioteca de la Academia Nacional de Historia. Caracas, 1967 | Plate from the book of Girolano Benzoni showing indigenous domestic activities. In Torres de Arauz, R. 1980: 56 Indigenous Panama. Panama: National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage. Benzoni, G. "The History of the New World." Library of the National Academy of History. Caracas, 1967.

El Rey Montezuma, dándose cuenta del hecho, murmuraba diciendo: “Así es la cosa, quiere decir que es extraordinario en fuerza y poder ese suguiá; entonces, es preciso que nos veamos con él, si es que tiene tanto poder y a ver si podrá vencerme también con su poder”.

El suceso no necesitó de tanto tiempo para que todos los moradores se dieran de cuenta y quedaran muy sorprendidos.

El suguiá Montezuma, quien estaba acostumbrado a hacerle frente a los colonizadores con su poder, a nadie temía, reconociendo que podía vencer a cualquiera en el preciso momento que le diera su gana. Con ese propósito, organizó un viaje maratónico desde San Félix al río Viguí, al lugar donde vivía el suguiá Concepción. La contingencia estaba compuesta por su familia, vecinos y sus allegados próximos. En su mayoría eran hombres y mujeres quienes fueron a ver cómo se realizaba la contienda y cuál iba a ser el resultado final entre los dos suguiás. Como la competencia era entre los dos soberanos e implicaba fuerza y poder extraordinarios, los seguidores sólo iban a estar de espectadores.

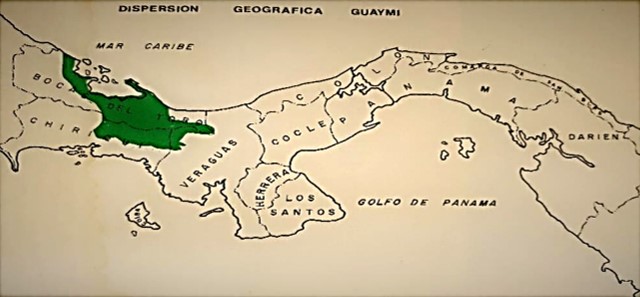

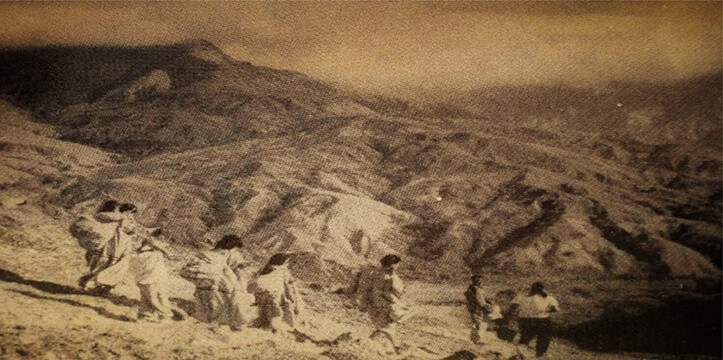

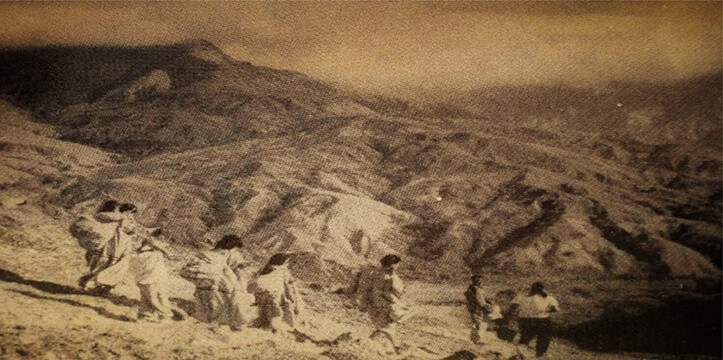

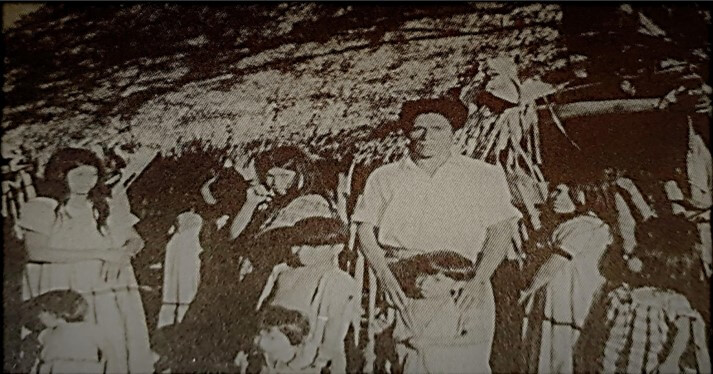

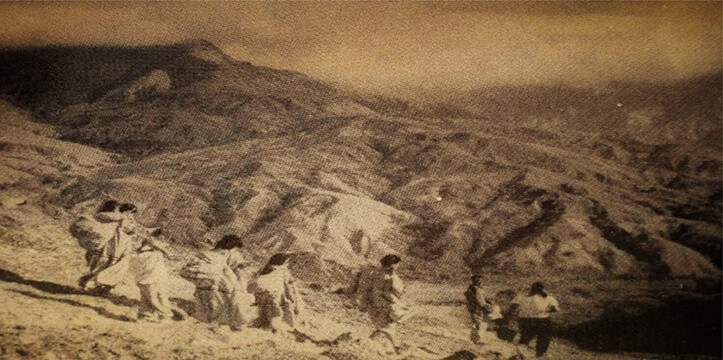

Guaymíes atravesando las montañas del Tabasará. En Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980:89 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Guaymíes crossing the Tabasará mountains. In Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 89 INDIGENOUS PANAMA. Panama: National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage.

Es costumbre encontrar donde los suguiás muchas personas quienes a diario acuden a consultar y pedir la vigilia. En los tiempos de la colonización, cuando todavía los indígenas Guaymíes (Ngäbe) no estaban mezclados en una sociedad mixta hispano-indígena, en que todavía no existían las influencias de religiones cristianas, sólo creían en suguiás quienes eran, como ahora, sus guiadores espirituales. A ningún hombre ofrecían culto, ni practicaban ciertas religiones extrañas con preceptos temerosos. Sólo creían en un ser supremo, cuyos máximos representantes en la tierra eran los suguiás. Por lo que el flujo de los seguidores de los suguiás era numeroso, encontrando donde ellos muchas personas concentradas diariamente.

Cuando el suguiá Concepción se percató de la maniobra que iba a realizar su homólogo Montezuma y de que estaba próximo a llegar a la casa, dio alerta a los suyos quienes estaban en ese preciso momento en la casa. Dijo a los seguidores que tuvieran tranquilos y que cuando llegaran los visitantes se mantuvieran unidos. Si cualquiera cosa extraña ocurriera, que nadie se asomara, que no hicieran comentario alguno, ni mucho menos ponerse a reír en el instante. Ya todos informados del caso y de la conducta que iba a regir, quedaron en espera de la llegada de la comitiva de Montezuma.

Efectivamente, hicieron su presencia en la casa del suguiá Concepción, encabezados por el jefe, el Rey Montezuma, quien inmediatamente saludó a Concepción, al mismo tiempo indicando cuál era el motivo de su visita. Luego, el mismo Montezuma indicó el modo de la contienda. El otro suguiá no puso objeción a la misma y sólo se limitó a cumplir y aceptar las reglas del juego.

Montezuma puso las siguientes condiciones para comprobar la capacidad y poderes de ambos: no orinar y no defecar durante cuatro días y noches. Durante estos días, los dos tenían que permanecer despiertos, pero tomando cacao en cada momento y abrazados, caminando y discutiendo sin que alguien supiera lo que se decían los dos.

Los seguidores del suguiá Concepción, los hombres se acomodaron en los asientos colocados en la casa y las mujeres se acomodaron en la cama hecha para los visitantes. De la misma forma, se acomodaron los del suguiá Montezuma.

Cama dentro de una casa Guaymí (Ngäbe) en Hato Pilón, San Félix. En Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 232 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Bed inside a Guaymí (Ngäbe) house in Hato Pilón, San Félix. In Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 232 INDIGENOUS PANAMA. Panama: National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage.

Los asientos siempre eran de palos labrados, de varios metros de largo, en que se acomodaban los visitantes y eran utilizados para grandes acontecimientos, reuniones para muchas personas. En uno de estos palos, se sentaron los acompañantes del suguiá Montezuma e iniciaron su encuentro formalmente con los lineamientos anteriormente establecidos. Sabiendo de antemano que los dos realmente tenían poderes ocultos, tanto los visitantes como los de la casa quedaron al tanto de lo que iba a ocurrir.

En una de las discusiones decía Montezuma a Concepción: “No vamos a orinar ni defecar durante estos días, los eliminaremos en cada uno de nosotros en forma de vientos y lluvias”; y así constantemente le recordaba al otro. En las camas en que se habían acomodado las mujeres de la casa y seguidoras del suguiá Concepción, en unas cuantas horas después del inicio, el Rey Montezuma comenzó su primer ataque, en la casa de su rival. Las camas en las que estaban sentadas las mujeres, las maderas y horcones que las sostenían se reventaron por las mitades, todas al mismo tiempo, quedando las mujeres regadas por el suelo. Los acompañantes de Montezuma se echaron a reír, mientras que los de la casa guardaron silencio.

Concepción respondió también a la hazaña de su contrario en un momento después. Los seguidores de Montezuma que se echaron a reír de lo que había pasado, estando sentados en la madera labrada, esta madera se rajó por la mitad violentamente, quedando partida en dos y todos los que estaban sentados sobre ella cayeron al suelo.

En ningún momento cesaba la bebida de cacao, días y noches. Las mujeres se encargaron de buscar agua y los hombres de buscar leña.

En una de tantas muestras de poder, en el preciso momento cuando las mujeres fueron a buscar agua en el pozo, el agua se volvió de diferentes colores. Entonces, cuando corrían a avisar a la casa lo que estaba pasando, el agua quedaba en su color normal, entonces la cogían en los cocos para llevarla a la casa.

La preparación de calabazas grandes para agua y chicha es una tarea masculina. En Torres de Arauz, Reina. 1980: 245 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | The preparation of big gourds for water and chicha is a male task. In Torres de Arauz, Reina. 1980:245 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico.

Esta era hazaña del Rey, volver el agua de colores; mientras que el otro hacía también la suya, volviéndola a su color normal. Supuestamente, los diferentes colores del agua eran las maldades que tiraba el Rey para ver si lograba acabar con el contrario y todos sus seguidores, cuando tomaran el agua.

Uno tras otro los sucesos fueron transcurriendo en la contienda de poderes, sin dejar que uno de los dos fuera a escaparse para tal fin. Permanecían abrazados ambos, sin dejarse libres.

Cuando transcurrieron tres días, el Rey se orinó en el pantalón abrazado con el suguiá Concepción; pero, continuaron ya que era reglamentario los cuatro días. Cuando llegaron al cuarto día, el Rey defecó en el pantalón. Ya se había acordado que nadie iba a hacer sus necesidades durante los días estipulados. Mientras, Marco Concepción permanecía de pie sin pasar por ninguna de las dos etapas. Esto significó entonces la derrota del Rey Montezuma, en su pretensión al no cumplir en todas las instancias con las normas de la confrontación.

Cuando el suguiá Concepción vio que su rival no pudo cumplir con la regla propuesta, él lo dejó libre para que fuera para su casa. Los seguidores de Montezuma vieron con sus propios ojos la derrota de su jefe.

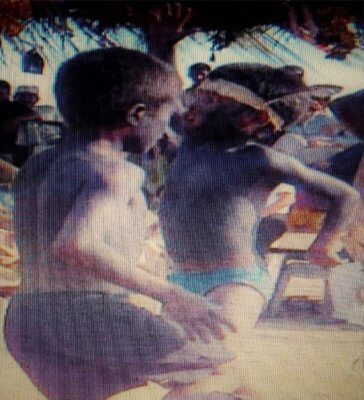

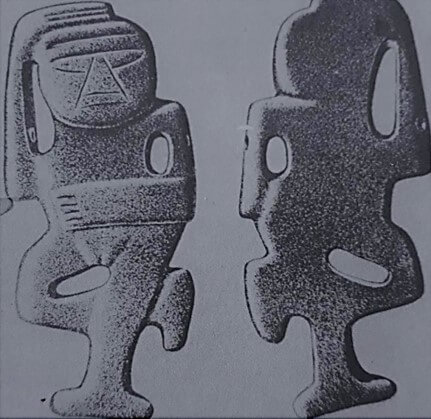

Pendiente de diseño olmecoide, procedente del oeste del Istmo. Tomado del libro de Lothrop Archaeology of Southern Veraguas. En Torres de Araúz, Reina 1980:54 Panamá Indígena. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Olmecoid design slope, coming from the west of the Isthmus. Taken from the Lothrop Archeology of Southern Veraguas book. In Torres de Araúz, Reina 1980: 54 Indigenous Panama. Panama: National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage.

Después del cuarto día, se fue para la casa la comitiva, siendo víctimas de otra forma por el suguiá Concepción. Ahora ya el ataque no era contra su rival Montezuma, sino contra todos sus seguidores. Ellos no podían sentarse en alguna parte en el suelo, encima de piedras, ni tampoco sobre palos, porque se quedaban pegados a ellos inmediatamente sin que ellos se dieran cuenta. Cuando se querían levantar, no podían y entonces comenzaban a llorar hasta que volvían a despegarse del lugar donde se sentaban, siguiendo con su comitiva para la casa.

Así anduvieron hasta que llegaron a su lugar en San Félix. Según un narrador, vieron todos lo que ocurrió. A medida que venían llegando a las casas, se iban muriendo uno tras el otro. Por último, quedó solamente el Rey, quien también sucumbió ante la muerte, para dar el fin a su contienda.

Mientras, Marco Concepción estuvo bien grave, pero siempre sobrevivió.

De esta forma se acabó el famoso suguiá conocido entonces como Rey Montezuma. Su muerte se le atribuye a que trató de subestimar el poder del suguiá Concepción, y que la gente no guardó la dieta reglamentaria. Como resultado, tuvo como consecuencia la confrontación entre los dos suguiás inútilmente, dejando como saldo la muerte del Rey y sus seguidores sin ser culpables. De no ocurrir tal hecho, no hubiera pasado alguna contienda en que tuviera involucrado el Rey, que pudo haber vivido más y que, tal vez, su lucha frontal contra los colonizadores la conoceríamos mejor y, quizás, con otros resultados no tan halagadores para los colonos quienes se establecieron en Remedios, de donde luego se expandieron.

Jefe de familia Guaymí (Ngäbe) con todas sus esposas e hijos, Cerro Culantro, San Félix. En Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 242 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Guaymí (Ngäbe) family head with all his wives and children, Cerro Culantro, San Félix. In Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980:242 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico.

(1) Este Rey Montezuma no se puede confundir con el Rey Montezuma de Méjico, a pesar de que su nombre sea igual. Al parecer, el Rey de Méjico fue conocido por el colonizador Hernán Cortés y el de Panamá fue conocido después, ya en plena colonización. Se sabe que fue recio adversario de la colonización, quien combatió con gallardía sin doblegar la cabeza en algún momento hasta llegar el momento de su muerte. El apellido Montezuma es común entre los indígenas del área de San Félix.

Dos figuras antropomorfas grabadas en petroglifo en Cuchilla de Bongo. En Conoce el Arte Rupestre en Panamá: Algunos Petroglifos en Chiriquí. Joly Adames, Luz Graciela, Compiladora, 2007:.28. David, Chiriquí, Panamá: Impresos Modernos | Two anthropomorphic figures engraved in a petroglyph at Cuchilla de Bongo. In Know the Rock Art in Panama: Some Petroglyphs in Chiriquí. Joly Adames, Luz Graciela, Compiler, 2007: .28. David, Chiriquí, Panama: Modern Impressions.

Foreword

FOREWORD

To facilitate reading in Ngäbere, we have adapted, with some modifications, the system in the short Ngäbere-Spanish dictionary Kukwe Ngäbere by Melquiades Arosemena and Luciano Javilla, published in 1979 by the Directorate of Historical Heritage of the National Institute of Culture (INAC), now the Ministry of Culture, and the Summer Institute of Linguistics.

It should also be clarified that this story comes from narrators residing in the village of Potrero de Caña, formerly the Tole district of the Chiriquí province, now the Müna district of the Ngäbe Buglé region, from which the Agronomist Roger Séptimo, the compiler and writer is a native. Consequently, the phonology corresponds to the dialectal or regional variation "Guaymí del Interior" (Pacific slope) which differs from the "Guaymí de la Costa" (Caribbean slope of the province of Bocas del Toro and the now district of Kusapin in the Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) in the Guaymí Grammar of Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, published in 1980 by Fe y Alegría. This variant corresponds to what Arosemena and Javilla call "Chiriquí" and which contrasts with the Caribbean variants of Bocas del Toro and the coast of Bocas.

This ethnohistory was published in 1986 in Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere / Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Ethnohistory Guaymí), by the Panamanian Association of Anthropology, with the PN-079 Agreement of the Inter-American Foundation (FIA) managed by Dr. Mac Chapin, Anthropologist, who encouraged us to follow the example he had set by compiling Pab-Igala: Histories of the Kuna Tradition, published in 1970 by the Center for Anthropological Research of the University of Panama, under the direction of Dr. Reina Torres de Araúz.

This book represented the work of the Agricultural Engineer Roger Séptimo, when he was a student in his second year at the Center for Agricultural Teaching and Research in Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, University of Panama (FCAUP), not only writing in Ngäbere the stories that he had heard from his family members in his community, but also his effort to translate them into Spanish as a bilingual person that he is, like other indigenous people in Panama, who are striving to receive a formal education.

The ethnohistories were compiled, recorded on cassettes and written by the Agronomist Roger Séptimo in 1983 and 1984.

As Professor-Researcher of Anthropology and Rural Sociology at the CEIACHI of the FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Anthropologist, Ph.D., encouraged Roger, as one of her students, to write the stories, convince him and show him that she would not exploit or abuse his work, but that he would get credit. Consequently, the anthropologist limited herself only to making some corrections of form and style in the Spanish translations without altering their content.

We encourage students from the seven indigenous peoples in the Republic of Panama, and teachers in public and private schools, colleges and universities in Panama, to write in their own languages and translate the ethnohistories and songs they hear in their families and communities into Spanish, as part of their informal education.

We also encourage readers of these ethnohistories in Ngäbere, Spanish and English, to draw the scenes that they liked the most, as they did in 2002, students in an Education and Society course, directed by Dr. Joly, at the Faculty of Education, Autonomous University of Chiriquí.

Article 13 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, approved by the General Assembly, in its 107th plenary session on September 13, 2007:

- Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, promote and pass on to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to name and maintain their communities, places and people.

- The States shall adopt effective measures to ensure the protection of this right and also to ensure that indigenous peoples can understand and make themselves understood in political, legal and administrative actions, providing for this, when necessary, interpretation services or other appropriate means.

REY MONTEZUMA AGAINST MARCO CONCEPCIÓN

Rey Montezuma (1), that was the name of a suguiá who lived in the mountain ridge of San Félix. Unfortunately, we do not know with certainty in what years he lived. He was a very powerful suguiá, chief of the Montezumas of San Félix.

This suguiá culminated his life in a contest that he had with another suguiá named Marco Concepción. Not much is known about Rey Montezuma as far as his life as a suguiá, nor is it known which were the battles that he had with the colonizers. What has been mostly remembered through time was his encounter with the suguiá Concepción, to measure the capacity and power of both.

The suguiá Concepción lived on the other side of the Viguí river, on the border with the province of Veraguas, near the place known nowadays as Cerro Pelado or as La Palma. Nowadays we still have his descendants, who still live in the same place.

Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980:216 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 216 INDIGENOUS PANAMA. Panama: National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage.

Now we shall narrate what happened and why they had to reach the extreme rivalry of their power, being both indigenous men and Guaymí (Ngäbe), above all. On the other hand, having external enemies, they should have fought them together and not provoke an internal fight between the two. It so happens that among the Guaymí (Ngäbe) there were many suguiás with extraordinary powers to protect their people and that together they looked after the wellbeing of their fellow citizens. All of them had a plural number of followers, who were free to choose which suguiá to consult whom they thought was the proper one. Therefore, there were Guaymí (Ngäbe) persons who would willingly go to various suguiás; or, as well, were recommended by the same suguiás, to join forces in common.

Under such circumstances, the Guaymi (Ngäbe) would travel long distances to where there were famous suguiás. It occurred that in San Félix, many indigenous people would go to the suguiá Marco Concepción, to consult him and seek his protection from evils. As is the tradition, the suguiás always authorize the religious ceremony of the wake to dispel evils. For such a case, the Guaymí (Ngäbe) who go to the suguiás always take cocoa so that the wake may be effective.

Thus, it occurred that many indigenous people from San Félix would go to the suguiá Concepción. They were neighboring families who periodically gathered and would go together to the aforementioned suguiá. Almost all would take cocoa so that they could receive the order to make their wakes. These facts were what one day provoked the contest between the two suguiás. According to the indigenous narrative, it occurred in the following way.

Beber cacao durante un velatorio, en Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 251. Panamá Indígena. Panamá, Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Drinking cocoa during a wake, In Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 251. Indigenous Panama. Panama, National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage.

As it was always customarily, a considerable numerously group of Guyamí (Ngäbe) people from the mountain ridge of San Félix arrived where the suguiá Concepción lived to consult with him and at the same time to give them the order to do the wake. It happens that before, it was customary to do a diet beginning with the first day of the wake, and it continued around five days for each wake. The diet consisted in not to eat salt, nor drink chicha (fermented beverage), nor eat any meat roasted over fire. Nowadays, very little or nothing is kept of this diet. When the order was given to hold the wake to several people at the same time, it was the norm that, as soon as the first wake ended, the second one began, and so successively until the last one ended, according to the order that the suguiá gave to each person. It meant that, not until the last wake ended, no one could break the customary diet.

These groups of indigenous people, as the days of the wake went by, they could not resist keeping the diet. As there were numerous families who were celebrating the wake, one after another, there would pass months without being able to eat salt, drink chicha, or eat anything roasted over fire.

These groups wanted to break the diet, as they could not resist any more to eat food without the condiment of the salt. They undertook the task to talk with each other, saying to try to eat salt. It was argued that the suguiá was living far away from where they lived and that, therefore, it was not possible for him to become aware of the same. Some said: “I don´t believe that he can become aware; he lives far from here; besides, there are many hills in between that make it difficult to see from there to here, and it is not possible that the suguiá can see or become aware that we have broken the diet.” Not being satisfied with the theory, they put into practice their desire.

With this idea, one of them, in the food that was being cooked, threw some salt. In the instant that the salt made contact with the food that was being cooked, all became ashes. In this way, they witnessed that it could not be done. No matter at what distance was the suguiá, this was impossible, as somehow his presence was wherever a wake was being held. In this way, their desire to break the diet was reduced to nothing.

Lámina del libro de Girolano Benzoni que muestra las actividades domésticas indígenas. En Torres de Arauz, R. 1980: 56 Panamá Indígena. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico. Benzoni, G. “La Historia del Mundo Nuevo”. Biblioteca de la Academia Nacional de Historia. Caracas, 1967 | Plate from the book of Girolano Benzoni showing indigenous domestic activities. In Torres de Arauz, R. 1980: 56 Indigenous Panama. Panama: National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage. Benzoni, G. "The History of the New World." Library of the National Academy of History. Caracas, 1967.

Rey Montezuma, becoming aware of this fact, murmured saying: “So that is the thing, it means that this suguiá is extraordinary in strength and power; then, it is necessary that we meet him, to see if he has such power and see if he can also win me with his power.”

It did not pass too much time so that all the inhabitants became aware of this incident and were very surprised.

The suguiá Montezuma, who was accustomed to confronting the colonizers with his power, not fearing anyone, recognized that he could win anyone at any time that he wanted. With this purpose, he organized a marathonic trip from San Félix to the Viguí river, to the place where the suguiá Concepción lived. The group was formed by his family, neighbors, and close followers. The majority where men and women who went to see how this contest was going to be and what would be its result. As the contest was between these sovereign men and it implied extraordinary strength and power, the followers were only going to be spectators.

Guaymíes atravesando las montañas del Tabasará. En Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980:89 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Guaymíes crossing the Tabasará mountains. In Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 89 INDIGENOUS PANAMA. Panama: National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage.

It was customary to find where the suguiás lived many persons who daily went for consultation and to ask for a wake. During the colonization, when the indigenous Guaymí (Ngäbe) had not been mixed into a Hispanic-Indigenous society, when still there were no influences of Christian religions, they only believed in suguiás who were their spiritual guides. They did not offer cult to any man, nor practiced religions with strange and fearful precepts. They only believed in a supreme being, whose maximum representatives on earth were the suguiás. Therefore, the suguiás had numerous followers, and every day could be found many people concentrated where the suguiás lived.

When the suguiá Concepción became aware of the maneuver that was going to be done by his homologous suguiá Montezuma who was getting close to arrive at his house, he warned his followers who were at that precise moment in his house. He advised his followers to be calm and to remain together when the visitors arrived. If anything strange occurred that no one should look, nor make any comments, and much less laugh at that moment. All informed of the case and the conduct that had to be observed, they remained waiting for the arrival of Montezuma and his followers.

Effectually, the visitors presented themselves in the house of the suguiá Concepción, led by their chief, Rey Montezuma, who immediately greeted Concepción, and at the same time indicated which was the motive of his visit. Then, Montezuma himself indicated the manner in which the contest would be held. The other suguiá made no objection and only limited himself to obey and accept the rules of the contest.

Montezuma set the following conditions to prove the capacity and powers of both: not urinate nor defecate for four days and nights. During those days, the two would remain awake, but drinking cocoa all the time, and walking embraced and discussing without anyone knowing what they were talking.

The followers of the suguiá Concepción, the men accommodated themselves on the seats inside the house and the women accommodated themselves on the bed made for visitors. The followers of the suguiá Montezuma accommodated themselves in the same way.

Cama dentro de una casa Guaymí (Ngäbe) en Hato Pilón, San Félix. En Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 232 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Bed inside a Guaymí (Ngäbe) house in Hato Pilón, San Félix. In Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 232 INDIGENOUS PANAMA. Panama: National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage.

The seats were always of elaborated trunks, several meters long, in which visitors would be accommodated and that were used for great events, meetings for many persons. On one of these seats, the followers of the suguiá Montezuma sat and the contest formally began with the rules previously established. Knowing beforehand that both really had hidden powers, both the visitors as well as those of the house remained expecting what would occur.

In one of their discussions, Montezuma said to Concepción: “We are not going to urinate nor defecate during these days, we will eliminate them in each of us in the form of winds and rain,” and thus he constantly would remind the other. In the beds on which the women of the house and followers of the suguiá Concepción had accommodated themselves, a few hours after the contest began, Rey Montezuma initiated his first attack in the house of his rival. The beds in which the women were sitting, the woods and forked poles that supported the beds burst in half, all at the same time, leaving the women spread on the floor. The companions of Montezuma burst in laughter, while those of the house remained silent.

A moment later, Concepción also responded to the feat of his adversary. The followers of Montezuma who were sitting on the elaborated boards of wood, the boards split violently in the middle, broken in halves, and all who were sitting on the boards fell to the floor.

The cocoa beverage did not cease at any moment, day and night. The women were in charge of getting water out of a well and the men went after firewood.

During one of the many manifestations of power, at the precise moment that the women went to get water out of the well, the water changed into different colors. Then, when the women were on their way to the house to inform what was happening, the water would recover its normal color, and then the women would fill the gourds to take the water to the house.

La preparación de calabazas grandes para agua y chicha es una tarea masculina. En Torres de Arauz, Reina. 1980: 245 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | The preparation of big gourds for water and chicha is a male task. In Torres de Arauz, Reina. 1980:245 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico.

This was the feat of Rey, to turn the water into colors; while the other suguiá also did his part, transforming the water into its normal color. Supposedly, the different colors of the water were the evils that Rey threw to see if he could finish his adversary and all his followers when they drank the water.

One after another, the incidents occurred in the contest of powers without letting any of the two, escape. Both remained embraced, without letting each other free.

When three days had passed, Rey urinated in his pants while embracing the suguiá Concepción, but they continued as it was obligatory for the contest to last four days. When they arrived at the fourth day, Rey defecated in his pants. It had been agreed upon that no one would make his necessities during the stipulated days. Meanwhile, Marco Concepción remained standing without passing through any of the two phases. This meant the defeat of Rey Montezuma, in his pretention, in not being able to comply in all the instances with the norms of the confrontation.

When the suguiá Concepción saw that his rival could not comply with the proposed rule, he let him free to return to his house. The followers of Montezuma saw with their own eyes the defeat of their chief.

Pendiente de diseño olmecoide, procedente del oeste del Istmo. Tomado del libro de Lothrop Archaeology of Southern Veraguas. En Torres de Araúz, Reina 1980:54 Panamá Indígena. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Olmecoid design slope, coming from the west of the Isthmus. Taken from the Lothrop Archeology of Southern Veraguas book. In Torres de Araúz, Reina 1980: 54 Indigenous Panama. Panama: National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage.

After the fourth day, the visitors left for their houses, being victims in another form of the suguiá Concepción. Now the attack was not against his rival Montezuma, but against all his followers. They could not sit anywhere on the ground, nor on rocks, neither on tree trunks, because they would immediately become attached without their becoming aware of it. When they wanted to get up, they couldn´t and then they would begin to cry until they could be detached from the place where they had sat and continue on their way home.

Thus, they went on until they arrived at their place in San Félix. According to the narrator, all saw what occurred. As they were getting near to their houses, they began to die one after another. At last, only Rey remained alive, but also fell dead, thus finishing the contest.

Meanwhile, Marco Concepción became very ill, but survived.

In this way finished the famous suguiá then known as Rey Montezuma. His death is attributed to the fact that he underestimated the power of the suguiá Concepción, and that his people did not keep the obligatory diet. As a result, the consequence of the confrontation between the two suguiás was futile, leaving as a result the death of Rey and his followers who were not to blame. If this event had not occurred, there would not have been any contest in which Rey would have been involved, who could have lived longer and that, perhaps, his frontal fights against the colonizers would be better known and, perhaps, with not pleasant results for the colonizers who established themselves in Remedios, from where they continued expanding.

Jefe de familia Guaymí (Ngäbe) con todas sus esposas e hijos, Cerro Culantro, San Félix. En Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 242 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Guaymí (Ngäbe) family head with all his wives and children, Cerro Culantro, San Félix. In Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980:242 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico.

(1) This Rey Montezuma cannot be mistaken with the Rey Montezuma of Mexico, even though the name is the same. Apparently, the Rey (King) of Mexico was known by the colonizer Hernán Cortés and the one in Panama was known afterwards, during the full colonization. It is known that he was a fierce adversary of the colonization, that he fought it bravely, never bending his head until his death. The surname Montezuma is common among the indigenous population of San Félix.

Dos figuras antropomorfas grabadas en petroglifo en Cuchilla de Bongo. En Conoce el Arte Rupestre en Panamá: Algunos Petroglifos en Chiriquí. Joly Adames, Luz Graciela, Compiladora, 2007:.28. David, Chiriquí, Panamá: Impresos Modernos | Two anthropomorphic figures engraved in a petroglyph at Cuchilla de Bongo. In Know the Rock Art in Panama: Some Petroglyphs in Chiriquí. Joly Adames, Luz Graciela, Compiler, 2007: .28. David, Chiriquí, Panama: Modern Impressions.

Rey Montezuma: suguia kä ne krere nomlen nünen Tödabata San Félix mintdon-ngualen temen meguera. Akua nünambare kä ñongualen metre kue abogo gare ñagare tari. Ne abogo suguia Töbata krií, dänguin Tödabo. Rey ne abogo ñan Rey Montezuma, dänguin ngäbre kualin sulia Hernán Cortés ye Méjico nügalin kä nebiti ngualen. Rey Montezuma Panamá nete ne genenan, Rey ne abogo toalin bä bitin kua.

Rey Méjico ne abogo toalin bári meguera suliagüe. Nöbälin ñagare jabata suliabe bata nomlen rüre käre bentre, ñara nigüite ñagare kälin arato, biti krütalin. Suguia ne krütalin ja gabata suguia gä Marco Concepción ben. Suguia ne abogo nomlen nünen ñó, rübare kue, rübare ñó kue, rübare ñó kue suliabe gare ñagare metre.

Kugüe bata kädriebare bäri temen, amlen bata kädrie tä matare, ne abogo rübare kue, ja galin kue, ja töi galin kue suguia Marco be kue nguanlen. Ne abogo ñóbata amlen nire bäri töi krií abogo tö namanlin gai.

Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980:216 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 216 INDIGENOUS PANAMA. Panama: National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage.

Suguia Marco abogo nomlen nünen ñö gä Miribata nagriri, nigüite juta Santiago gri, Jugribata, kä gä Las Palmas kenta temen. Ne abogo mrägä kue tä nünen ne ngontitda temen matare. Ne abogo ñóbata jagalin kue.

Suguiare röare amlen ngäbere arato amatibe. Ne arato ameln rüe mentenlin genenan suliare nomlenna, neben rüdre kuetre jañate bä amatibe jagüe be ngäbare roärebe namanlintre ja gain, ne ñóbata amlen meguera niguen ngäbe götäitetda temen suguia nomlen nünen kuatií töi kriígri be jogrä abogo nomlen ngäbe guibiagrägä jire, ne abogo jañäte nomlen ngäbe guibiare niguen temen. Ni neguete kuatií bata érebe niguen temen. Ne amlen töi kue biti, suguia ñó ngonti tö nomlen nebe nain nomlen niguentre. Ne abogo bata ngäbe itibe nomlen nebe suguia kuatií ngonti, ne amlen erenguan-nen suguia nomlen juen suguia mada ngonti arato, abogo ja di miare kue jañäte abogo gäre. Ne abogo bata ngäbe nomlen nebetre näin move niguen suguia töi kriígri ngonti ja driere ie, kä göböguite ie. Ne krere bata ngäbe Tädäbo nomlen nebe kuatií kä göböguite, ja driere suguia Marco ye Maribata.

Ne nguan-re abogo suguia kä göböguite, kä göböi bien ngäbeye, ja mogore, kóra güete niguen temen. Ne aicete ngäbe nebe suguia ngonti, niguen kä nguenan käre, käböguitare. Abogo suguia köböi bien käre arato ietre. Ne krere abogo ngäbe Tädäbo nebe kuatií käre kä köböguite Marco ye. Nomlen niguen kuatií guaiare jabata.

Beber cacao durante un velatorio, en Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 251. Panamá Indígena. Panamá, Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Drinking cocoa during a wake, In Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 251. Indigenous Panama. Panama, National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage.

Jagüe be nomlen ja ügugre cabre nomlen niguentre kä göböguite suguiaye. Nomlen niguentre noi näre jabata erere nomlen niguen kä nguenan érebe jogrä köböguitare suguiaye.

Kugüe ne krere bata suguiagüe ja galin ne nguan-re ngäbe nguarabe guebeite.

Kugüe ne abogo nögalinga krörö nieta ngäbegüe. Ne kä mada nguanre krere ngäbe Tädäbo namanlin kuatií jabata suguia Marco ngonti kä göböguite ie. Meguera, ne nguanlen amlen ngäbe nomlen nebe bäin kä nomlen ngötäi näire, kä abogo nomlen noen mögäite, kratire érebe. Bäin nomlen nebe, mren ye, jondron kugualin ñüguate ye. Matare bäin ta ñácara bogän ne krere. Ni kuatií nain jabata nebe suguia ngonti kräga kä göböguita nomlen kue amlen kä krati guidianga näire te mada göta, abogo niguen ja jiöbiti kratire, kratire ta, ne krere niguentre jogrä ta.

Lámina del libro de Girolano Benzoni que muestra las actividades domésticas indígenas. En Torres de Arauz, R. 1980: 56 Panamá Indígena. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico. Benzoni, G. “La Historia del Mundo Nuevo”. Biblioteca de la Academia Nacional de Historia. Caracas, 1967 | Plate from the book of Girolano Benzoni showing indigenous domestic activities. In Torres de Arauz, R. 1980: 56 Indigenous Panama. Panama: National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage. Benzoni, G. "The History of the New World." Library of the National Academy of History. Caracas, 1967.

Suguia nomlen köböguite krere nomlen niguen ngöti bata niguenta ja jiöbiti arato kä göböguita nomlen kälin nomlen götäi kälin arato abogo niguen guedengä ja jiöbiti. Ne aicete abogo bäin nomlen nebe amlen, kä rigai jogrä ta amlen batibe jondron küan nomlenta jai ngöbegüe. Kä rigadre ta jogrä amlen batibe, ne krere ñagare amlen jondron ie bäin nomlen nebe ñan nomlen nebe kuatare, nomlen nebe kuatare tare.

Tödabo janamlen kuatií kä göböguite suguia ye Miribita, nebiti mrä amlen kä ñan jatalin nügue ietre bäin bata, amlen kä ñan namanlin niguen jötrö ta ne abogo nomlen nebe kuatií jabata aicete kä nomlen niguen ngötäi girere ja jiäbiti kuetre, ne abogo nomlen noen raire jabata, eranguanen sö nomlen niguen bäre, bäre jabata kä ñabata ietre. Konti ñan nomlen nebe mren guatabare ietre, dö, bata jondron kugalin ñüguäte. Ne krere bata känan jatalin nüguetre ie jondron tibo bata. Ñan tö jatalin jondron tibo guatai, tö namalin mren guataiatre abogo namanlin ja töidentre mada. Namanlintre niere jai, ne ñóröbäre ñan nomlen mren 7 guetetre, suguia ne abogo nomlen nünen move temen, nomlen tre nünen ngonti aicete abogo ñan gadre suguiagüe, nomlentre mren güete ya o ñagare ñan gadre suguiagüe namanlin nieretre. Mada namanlin niere abogo “Ne gadreraba kue ya, tä nünen move sete ne abogo, amlen ngütio kriígri kuatií jingrabe arato ne abogo öguä sete rü gairabe nete ya, ne ñan öguä rabai neguetegä gütiobata ya, ne kä jatadreraba ie nete ya, nigüe mren guata abogo jatarearabe ie ya”, manlintre niere, ne abogo ñägäbare kuetre ñan namanlin era abogo ben noembare bögänlen kuetre. Ne krere namanlin töbiguetre kägüe mren guitalin nguinse mröria nomlen kuetreté. Mren nigalin nguitiegä nguinse, nigüitalimen ngübrünen jogrä nguinse. Amlen galintre kue, ne nin rabadre noembare ietre, suguia nomlen mente gua kä kälimen kräga, tädre mente gua kä kälimen krägä, tädre mente ya o kälimen ya ne nomlen guiere noenen gare kuin ie. Ne abogo nomlen töibiti nünen bentre, ne abogo ngäbe nguibiare käte niguen temen. Kugüe nögaga krörö bata nin nibi mren guatalin ietre amlen nebe bäinretre tätde ie. Nebe jamigare tätde ietre.

Guaymíes atravesando las montañas del Tabasará. En Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980:89 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Guaymíes crossing the Tabasará mountains. In Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 89 INDIGENOUS PANAMA. Panama: National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage.

Kugüe ne abogo Rey Montezuma kägüe galin mada nin namanlin debe krägä, amlen namanlin ñägue “Se erere ya, se töi krií bogänlen ya, suguia ne abogo töi krií, di krií ñañan, ne abogo grä rebei ja töadre tigüe ben, ti nain konti era bogänlen ya, ne abogo di krií, toi krií abogo tigüe ja gaiben ti galaindi kue arato ne amlen tigüe mie tätde” niebare kue.

Kugüe ne güe nin nüalin raire amlen namanlin-ra gare jogrä ngäbeye niguen ja kenta temen. Ne abogo kädrie namanlin batibe nigen jogrä temen.

Suguia Montezuma abogo käre rüre ribanga suliare ben, niguen ja kentda temen, aicete abogo kä jurä ñacara bata, amlen galain ñácara ribanga suilaregüe arato. Ne abogo bata töi rüi ribangabe, ni jogräbren tö jagai.

Ne krere bata ja koböi guitalin kue nongrä Tädäbata nebe Jugribata, nebe suguia Marco konti. Nigalin kuatií jabata, suguia mrägä ngäbe nünanga jaken kontita temen, neguetebata, merire, brare nigalintre jabata, guiere neonditre suguiagüe, amlen rebeitre ñó jagrä kuetre abogo nigaliantre mie ñaräre. Ne amlen suguia kriígri roärebe rigüitaitre jabata aicete nongä bata abogo nigalin nguarabe mrüsen.

Suguia abogo bata ni ngötäi kuatií käre kä göböguite ie. Ne abogo meguera, krere noen tä matare arato.

Sulia jatalin nügue kenan kä nebiti temen ne amlen nünan ngämin suliabe mlin-mlin niguen temen, ne amlen kugüe ja guetare ngöböbata ngämin nain temen arato, ne nguan-re amlen ngäbe neguete suguia bebata abogo be miga tätde niguen temen.

Cama dentro de una casa Guaymí (Ngäbe) en Hato Pilón, San Félix. En Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 232 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Bed inside a Guaymí (Ngäbe) house in Hato Pilón, San Félix. In Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 232 INDIGENOUS PANAMA. Panama: National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage.

Ngäbe suguia be migue tätde jai, ne ñóbata amlen suguia ne abogo ie ngöbö ja di bien, ja töi bien abogo biti töi kriígri nie ngäbegüe ja érebe jogrä niguen temen abogo bata aibe mie tätde. Ne abogo ñan ni nire güite ngöböre jai, ñan neguete kugüe bätägä nguarabe bata, amlen neguete kügüe kuatibe bata abogo miguetre tátde jogrä. Ne abogo töibiti neguetetre ngöbö itibe bata, ngöbö ne abogo suguia migue niguen temen abogo ngäbe guibiägä Käre gäre, niere tre. Ne abogo bata ngäbe neguete suguia be bata jogrä niguen temen aicete abogo ni kuatií käre suguia ngonti nieguen kä ngrabre temen. Ne abogo suguia nünanga jugribata kagüe Rey Montezuma kugüegalin, Rey nomlen guiere nütre ñara bata galin kue jabata ben guairebe akua ñara abogo namanlin nguibiare jiriabe.

Rey tö namanlin guiere noeinben galin kue, ne amlen nebera jaken guägära bata, galin kue amlen jötrö nguarabe niebare kue ngäbe nomlen konti ye, dongui nügue jaken niebare kue, ne amlen Rey nüguera jaken guägäre ie. Amlen ñägäbare kue ngäbe neguete bata ie, nünamlan jämen kue, kä migamlan kueguebe kue. Rey rabai amlen nam-len kugüe ñó rögaga, ñan kädriemlan kue, ñan kötamlan kue, kugüe rögadregä ñan ngüe amlen ñägäbare tre ie krörö seguiagüe biti namanlin sugia Rey Montezuma nguibiare guägäre. Ne krere vatibe Rey matamanlin guägäre bogänlen, ni kuatií abogo ñara nain jie nguën kälin nigalin mate guägäre, köbö nguanlintari kue suguia miriboye kuebiti nomlen ñain ñó tari niebare kue suguia ye. Biti Rey arabe kägüe niebare suguia itiye ja gai ñó kue niebare kue, suguia miribo abogo kägüe ñägäbare ñagare 9 käre namanlin nguibiare. Rey güe jagai ñó, guiere noendi ja di gagrä, ja töi gagrä, ne abogo nire bäri töi krií, nire bäri di krií abogo gagra gäre. Rey güe niebare suguia miribo ye.

La preparación de calabazas grandes para agua y chicha es una tarea masculina. En Torres de Arauz, Reina. 1980: 245 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | The preparation of big gourds for water and chicha is a male task. In Torres de Arauz, Reina. 1980:245 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico.

Ñan itranin gai nigüe ñan nondi kuguen nigüe kuäítde dibire, rare niebare Rey güe. Ne abogo noandre kuäítde kuetre nin kibiadre rare, dibire kuetre amlen kä ñadre dibire rare arato kuetre küde guitalin ja ngäre, diguegä güita amlen ñaguetre jai. Ne krere näembare tre kue bogänlen akua ne nguietre nie nomlen tre kuetre jai abogo gare ñagare tari. Neguetagä suguia Concepción bata, braretre abogo kägüe ja ügalinte kribiti amlen meriretre abogo kägüe ja ügalinte niguen jonbiti niguen güita temen, krere nongätre suguia Montezuma be ügalinte güi arato.

Ne amlen ja tägrä abogo kri sögalin kuata kriígri be migalin niguen güita temen ja tägräre, abogo ni rabadre kuatií biti gäre, ni ngötäi kuatií abogo tägräre, ne abogo tägäre ni brare be ie amlen merire abogo tägue jonbiti, ere-nguan-nen abogo kimon mia nomlen tägräre. Ja tägrä ne krere biti nongä suguia Montezuma be namanlin tägälinte güi suguia Concepción ngonti. Namanlin-ra ja ügalintetre jogrä güi amlen suguia nigalin ja gain oguäbititre. Niebare Rey güe krere. Ne amlen nibu töi kriígri ja érebe aicete reguetagä batatre namanlin nguibiare guiere noenditre kuetre abogo guibiare kribiti, jombiti niguen güita temen. Namanlin ñague tre jai niguen guita temen bätägäbe nguarabe, ne ere-nguanen Rey güe nie suguia iti ye nigüe ñan itranin gai, nigüe ñan nondi küguen kä ne nguan-re nigue jueingä jabata ñüre, mürere; ne krere namanlin nebe ngüen tda töre jötröguä be suguia Concepción ye.

Nebiti jon güi biti meri nomlen suguia Concepción ngonti nomlen tägälinte niguen güita temen vatibe ürä nötälingä guaire jogrä talin nigüitalingä jogrä temen, meri nomlen kuatií tägälinte biti nigalin ngitiegä jogrä temen jonbiti. Amlen nongä Rey be kägüe kötabare guaire jabata jogrä, amlen ngüire abogo namanlinbe kueguebe, kägüe kötabare ñagare, kugüe ne abogo noembare Rey güe, ñaragüe kugüe noembare kälin suguia itibata.

Suguia Concepción abogo kägüe ñan teibabare amlen noembare krere arato kue jötrö nguarabe kue. Nongä Reybe namanlintre ködetre jabata kugüe nögalingäbata, nomlen tägälinte niguen kribiti temen güita jämen batibe kri nialinga kumun tanlin, vetalingäbe mentö ngualen, nomlentre kuatií kribiti nigalin nguitiegä jogrä temen. Ngäbe güiri namanlinbe kueguebe jogrä nin kötabare kuetre namanlin mie ñäräre jiriäbe.

Pendiente de diseño olmecoide, procedente del oeste del Istmo. Tomado del libro de Lothrop Archaeology of Southern Veraguas. En Torres de Araúz, Reina 1980:54 Panamá Indígena. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Olmecoid design slope, coming from the west of the Isthmus. Taken from the Lothrop Archeology of Southern Veraguas book. In Torres de Araúz, Reina 1980: 54 Indigenous Panama. Panama: National Institute of Culture, Historical Heritage.

Ne amlen kä namanlin krütde ñácara nguinsen dibire, rare; meri güire namanlin ñö tdigue guagäre amlen brare abogo namanlintre nebe ngui den guägäre. Ne amlen suguia abogo küdeguitalin ja ngäre ñague jai niguen güita temen. Amlen te meri ngalin ñó den mötda amlen ñöguä mötda nigüitalin bätäbe nguarabe, bä namanlin nebe rerebare, tain, mire sübrüre erenguanen. Bata nigalin begäta guä kägüe niebareta suguia Concepción ye abogo kägüe kuitalinta ngüen amlen merigüe dialin mrüte nguanre guagäre. Ne krere nigalin jabata tre matde kuetre. Rey güe ñö kuita bä genen abogo suguia Concepción kägüe kuitata ngüen abogo namanlintre nuenen möta . Ñö bätäbe nguarebe ne abogo Rey gäbä. Ne abogo ñö bä namanlin nebe bätägä nguarebe ne abogo bren guita nomlen Rey güe ñötde, abogo ñadre suguia Concepción güe, ngäbe güiri güe, abogo bren ne reguetaiga bata kägüe ñagä abogo kitadregä jogrä gäre, ne krere abogo galandre kue gäre; kugüe ne krere bata mada nigalin nögaingä dibire, rare amlen kä jatalin niguen raire jabata ta ietre, amlen ja guibiegä ñacaretre, nam-len iti riate abogo ngänlinen küde guitalin ja ngäre güi abogo ja nguibiaretre. Ne krere kä nigalin köbömä ta ietre jabata amlen Rey güe itranin galin jabata güi küde guitalin suguia Concepción be ja ngäre, ne akua nomlen jabata amlen känomlen käböti kalintre. Kä jatalin nügue mogäite ietre amlen Rey güe kälin jabata. Ne amlen kä migalintre mogäite ja kälin kuetre ne abogo nomlen miguetre tätde, ne amlen ñan itranin gai, ñan nondi küguen niebare tre kue jai arato kena ñan namanlin tätde Rey ye. Amlen suguia jugribo abogo nomlen kuin jabata abogo kägüe kälin ñagare jabata. Ne amlen Rey nianlintdera suguia jugribo be jabata, kugüe ügalintetre kue jagagrätre erere ñan namnlin tätde Rey ye nongä ben öguäbiti. Kä ñan nügalin mogäite Rey ye suguia jugribo öguäbiti, amlen kä nügalin mogäite ietre, 11 amlen Rey guibialingä kue, toalinmlen kaibe kue, jataita ja griete gäre. Nongä Reybe öguäbiti Rey nialinte käntdre suguia jugribo guisete.

Mogäirara amlen jatalinta tre ja guäreta Rey be, amlen nibialintebe bä genen mada suguia jugribo ye, ne amlen ñan Rey be, amlen nongä reibe erere nibialintibe jogrä ie.

Tagä temen dobobata kue, reguetagabe bata, tögä kuetre jäbiti regueguetagabe Jäbata, ne ben tägä kuetre kribite amlen regueta kabe kribati ñäre ñácare tari, ne abogo raba tägälin temen jaba naingre jötrö krö amlen neguetalingä temen ne abogo riga ja müairete te nomlen nguedengä bata, amlen nomlen kite ta, ne jatalin nögaingä bata tre kite jingrabre, ja guäreta. Ne krere jatalin nögaingä tre bata kite jingrabre, te nügalinta tre Tädäbata. Kugüe ne abogo kodriebare ni nguarabe kägüe, jatalin siba arato kugüe gain, öguäbiti kugüe nögalingä kägüe niebareta. Ni ne güe niebare abogo, jatalin tre nügüeta Tädäbata amlen nongä Reybe erere nigalin krüte itire, itire ja jiöbiti krütalintre jogrä amlen Rey be namanlin mrä, abogo krütalin mrä arato, ne krere krütalintre jire jogrä. Kuegüe ne biti, amlen suguia jugribo abogo kägüe ja bren noalin krií akua abogo krütalin ñagare. Kugüe ne krörö bata suguia Montezuma krütalin, jagabata nguarabe, tö ja gabata ni töi kriigriben bata suguia mada töi ñan mialin tätde kue jagrä abogo ngonti, ne amlen arato, abogo ngäbe Tädäbo kägüe ñan ja mianlin tätde kuetre, tö namanlin suguia töi gain ngonti Rey niguitalin jötro nguarabe suguia jugribobe jabata abogo guebeite. Kugüe nögalingä krörö ngonti, suguia nguarabebe kägüe ja galin konti Rey guidialin. Kugüe ne ñan rögadregä krörö, ne nin Rey krütadre jotrö grere gua, kugüe nebata krutalin jötro nguarabe ne abogo rüdre kue, ja gadre sulia be ben kue abogo grä kugüe ne rabai bä genen grere gua, akua kugüe nögalingä krörö. Ne ñódre kue jabata sualiabe kue ne ñagare. Ne Rey Montezuma krütalin krörö, ñan krütalin bren guisete, ñan krütalin sulia guisete, krütalin ja gabata suguia jugribo ben, ne abogo gare kröro ngäbe ye.

Jefe de familia Guaymí (Ngäbe) con todas sus esposas e hijos, Cerro Culantro, San Félix. En Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980: 242 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico | Guaymí (Ngäbe) family head with all his wives and children, Cerro Culantro, San Félix. In Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980:242 PANAMÁ INDÍGENA. Panamá: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Patrimonio Histórico.