Prólogo

PRÓLOGO

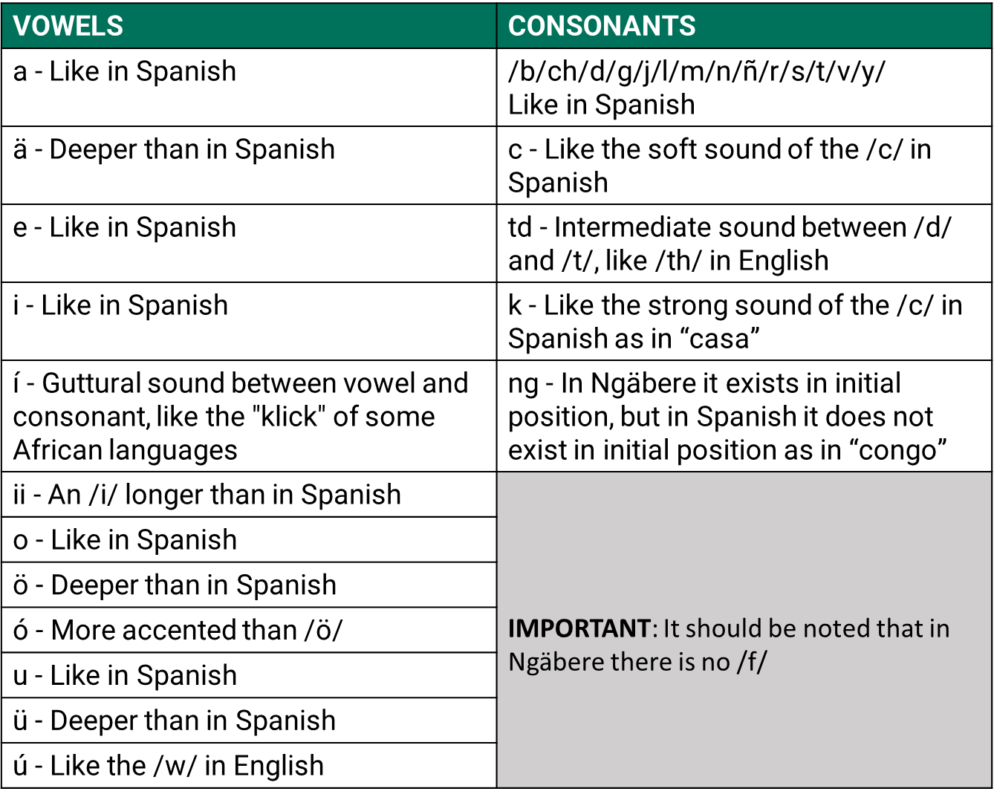

Para facilitar la lectura en ngäbere, hemos adaptado, con algunas modificaciones, el sistema en el breve diccionario ngäbere-español Kukwe Ngäbere de Melquiades Arosemena y Luciano Javilla, publicado en 1979 por la Dirección del Patrimonio Histórico del Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INAC), ahora Ministerio de Cultura, y el Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

También conviene aclarar que esta historia proviene de narradores residentes en el corregimiento de Potrero de Caña, antes distrito de Tole de la provincia de Chiriquí, ahora distrito de Müna de la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé, de donde es oriundo el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, el recopilador-escritor. Por consiguiente, la fonología corresponde a la variación dialectal o regional “Guaymí del Interior” (vertiente del Pacífico) y que difiere del “Guaymí de la Costa” (vertiente caribeña de la provincia de Bocas del Toro y del ahora distrito de Kusapin en la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) en la Gramática Guaymí de Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, publicada en 1980 por Fe y Alegría. Esta variante corresponde a la que Arosemena y Javilla denominan “Chiriquí” y que contrasta con las variantes caribeñas de Bocas del Toro y costa de Bocas.

Esta etnohistoria fue publicada en 1986 en Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere/Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Etnohistoria Guaymí), por la Asociación Panameña de Antropología, con el Convenio PN-079 de la Fundación Inter-Americana (FIA) gestionada por el Dr. Mac Chapin, Antropólogo, quien nos animó a que siguiéramos el ejemplo que él había sentado al recopilar el Pab-Igala: Historias de la Tradición Kuna, publicadas en 1970 por el Centro de Investigaciones Antropológicas de la Universidad de Panamá, bajo la dirección de la Dra. Reina Torres de Araúz.

Este libro representó la labor del Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, cuando era estudiante en su segundo año en el Centro de Enseñanza e Investigación Agropecuaria de Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad de Panamá (FCAUP), no solo de escribir en ngäbere las narraciones que había oído relatar a sus familiares en su comunidad, sino también su esfuerzo de traducirlas al español como persona bilingüe que es, al igual que otros indígenas en Panamá quienes se esfuerzan por recibir una educación formal.

Las etnohistorias fueron recopiladas, grabadas en casetes y escritas por el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo en 1983 y 1984.

Como Profesora-Investigadora de Antropología y Sociología Rural en el CEIACHI de la FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Antropóloga, Ph.D., animó a Roger, como uno de sus estudiantes, a escribir las historias, convencerlo y demostrarle que no explotaría ni abusaría de su trabajo, sino que se le reconocería su mérito. Por consiguiente, la antropóloga se limitó solamente a hacer algunas correcciones de forma y estilo en las traducciones al español sin alterar su contenido.

Animamos a estudiantes de los siete pueblos originarios en la República de Panamá, y a docentes en escuelas, colegios y universidades públicas y privadas en Panamá, a que escriban en sus propios lenguajes y traduzcan al español las etnohistorias y cantos que escuchan en sus familias y comunidades, como parte de su educación informal.

También animamos a lectores de estas etnohistorias en ngäbere, español e inglés, a que dibujen las escenas que más les gustaron, como hicieron en el 2002, estudiantes en un curso de Educación y Sociedad, orientado por la Dra. Joly, en la Facultad de Educación, Universidad Autónoma de Chiriquí.

Artículo 13 de la Declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas, aprobada por la Asamblea General, en su 107ª sesión plenaria el 13 de septiembre de 2007:

- Los pueblos indígenas tienen derecho a revitalizar, utilizar, fomentar y transmitir a las generaciones futuras sus historias, idiomas, tradiciones orales, filosofías, sistemas de escritura y literaturas, y a atribuir nombres a sus comunidades, lugares y personas, así como a mantenerlas.

- Los Estados adoptaran medidas eficaces para asegurar la protección de ese derecho y también para asegurar que los pueblos indígenas puedan entender y hacerse entender en las actuaciones políticas, jurídicas y administrativas, proporcionando para ello, cuando sea necesario, servicios de interpretación u otros medios adecuados.

Hace mucho tiempo vivía una viejecita. Ella vivía sola, lejos de toda su familia. Todos los días tenía carnes en abundancia. La gente no se explicaba por qué motivo, siendo ella mujer y sola, podía tener tanta y permanentemente las carnes de cacerías.

Exposición y cédula en el Museo de Panamá Viejo, foto LGJA 26/07/2019 | Exhibition and identity card in the Museum of Panama Viejo, photo LGJA 07/26/2019.

Un día uno de sus nietos, con interés de conocer cómo era realmente que su abuela tenía muchas carnes de cacerías, decidió una tarde ir a pasear donde la abuela. Estando donde la abuela, anocheció; pero él no intentó regresar, ya que fue con la intención de quedarse y no regresar hasta saber con certeza la realidad de la cacería de la viejita. Cuando anocheció, la viejita no sabía qué hacer con su nieto y no le quedó otra alternativa que hablarle al nieto. La viejita dijo a su nieto que tratara de orinar lo máximo posible y luego se fuera a dormirse en el jorón y que no intentara en ningún momento de bajar del jorón en la noche. El astuto nieto solamente se limitó a hacer y cumplir lo que le dijo la abuela y subió al jorón.

Cuando cayó la noche, vinieron llegando a la casa por los cuatro puntos cardinales tigres de todos los tamaños y colores. En la casa había asientos de madera en forma de tablones, que aún es muy común en las regiones guaymíes (ngäbe). Estos asientos formaban un círculo dentro de la casa, que al principio sorprendió al transeúnte que no entendía cómo era posible que la viejita, quien no acostumbraba a recibir visitantes, tuviera demasiados asientos en la casa. ¿Para quién o para qué eran esos asientos? Preguntaba a sí mismo el nieto. Esta duda paulatinamente se fue despejando y abandonando su mente.

Acostado en el jorón mirando entre las rajaduras de la cama de bambú o trozos de la corteza de pixbae, veía a los tigres llegar e ir acomodándose inmediatamente en fila sobre el asiento. Otros que llegaban se iban a acostar en la cama con la viejecita; es decir, éstos eran los preferidos de la abuela y los acariciaba como si estuviera acariciando a gatos domésticos. Algunos llegaban con cacerías de diferentes clases.

Radical Distilling, Tierras Altas, Panamá 2017 | Radical Distilling, Highlands, Panama 2017.

Él observaba todo lo que estaba ocurriendo abajo. Sabiendo ya para quiénes eran los asientos, se limitaba sólo a moverse en la cama arriba del jorón. Con el ruido, los tigres rugían al mismo tiempo y se ponían en posición de saltar a atacar. La viejita les daba con la mano en la cabeza, como tratando de calmar a los tigres. En esa forma transcurrió la noche hasta el amanecer.

Cuando vino amaneciendo, los tigres, uno por uno, fueron desfilando y saliendo de la casa hasta desalojarla por completo. Entonces, él se bajó del jorón ya convencido de haber dado con su investigación.

La viejita le dijo: “Por favor no comentes para nada lo que tú vistes aquí y no se lo digas a nadie; esto es privado y secreto de mi propiedad”.

Pero como siempre, no hay nada que no se comente, ya sea pronto o a la larga, pues nada queda oculto, porque siempre habrá alguna persona que no dejará pasar mucho tiempo para contar las cosas. El nieto se fue corriendo para la casa y con asombro comentó lo que había visto, sin hacer caso a la advertencia de la abuela.

En ese tiempo también vivía un extraordinario cazador conocido como Nici Köguatda, quien se dio cuenta de lo mismo e inmediatamente trató de conocer a la señora y, además, saber si tenía hija. Efectivamente, la doña tenía una hija que aparentemente no vivía con ella. Nici fue a la casa donde vivía la viejecita y le pidió que le diera a su hija para que fuera su esposa. Yernos de la señora y otros individuos, con afán de ver consumida a la señora por dedicarse a la brujería, recomendaron a Nici, diciéndole a la doña que era un formidable cazador y un extraordinario hombre y que ella no iba a tener problemas, sino que iba a estar a su servicio y al cuidado de su mantenimiento. Al principio a la doña no le pareció tan halagadora la idea y no aceptó la propuesta de Nici, ni la de sus amigos.

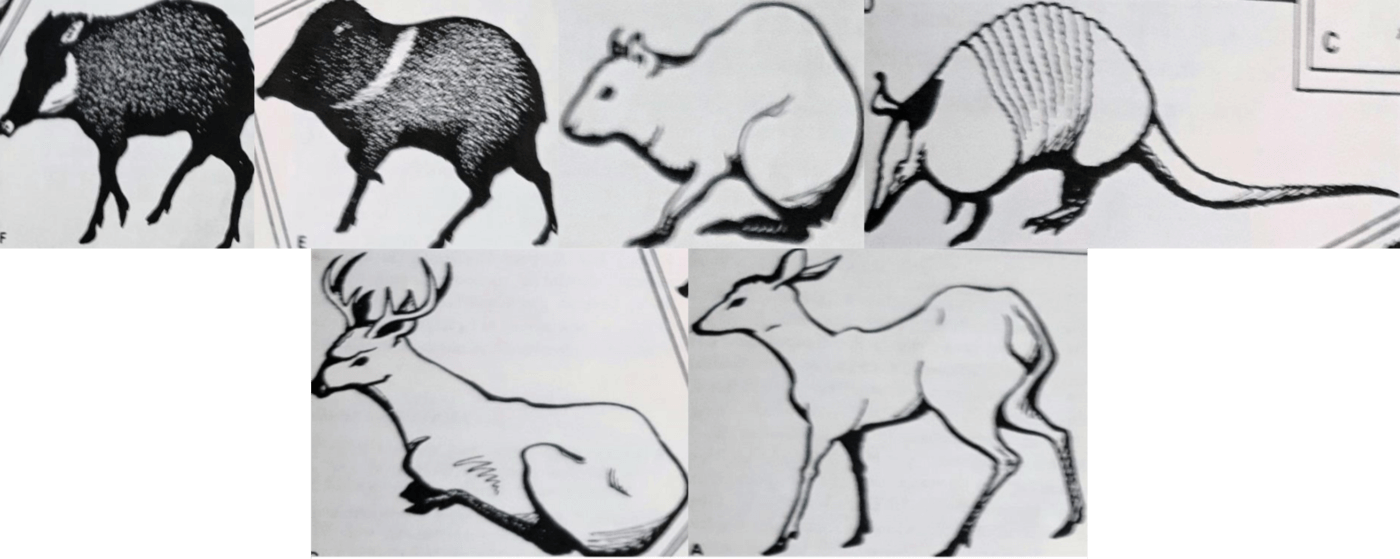

La botánica y la historia natural de Panamá: La Botánica e Historia Natural de Panamá. Editores William G. D´Arcy Jardín Botánico de Missouri y Mireya D. Correa A. Universidad de Panamá. Saint Louis, Missouri, Jardín Botánico de Missouri, EE. UU., 1985 | The Botany and Natural History of Panama: La Botánica e Historia Natural de Panamá. Editores William G. D´Arcy Missouri Botanical Garden y Mireya D. Correa A. Universidad de Panamá. Saint Louis, Missouri, Missouri Botanica Garden, USA, 1985.

Pero Nici se mantenía incansable en su deseo. De tanto decirle, convenció a la doña y ésta la entregó la hija. La insistencia de Nici no era más que una maniobra para enterarse de la brujería que practicaba la doña y buscar de alguna manera acabarla. No era tanto el deseo de casarse con la hija de la viejecita, ni tampoco de querer servirla a ella, sino el de matar a todos los tigres que tenía la viejecita bajo su poder, ya que estos eran los que hacían daños, comiéndose a los terneros que habitaban los llanos.

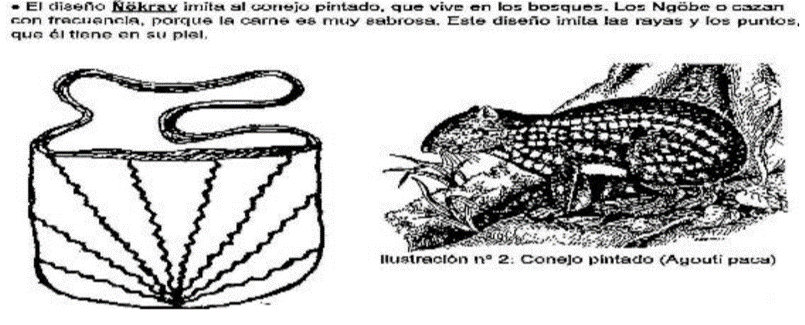

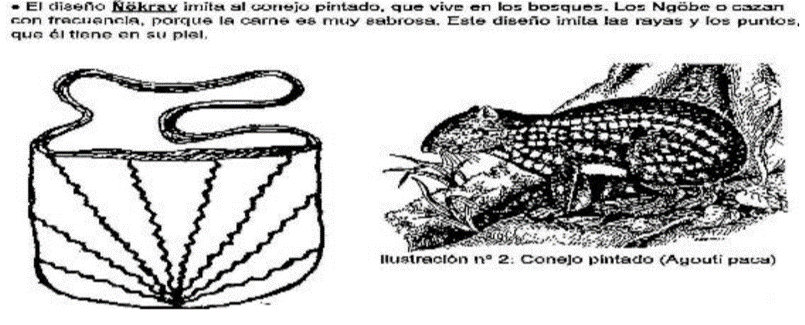

Documento Ngöbe Tomo XII La Chácara—Arte Vivo de la Mujer Ngöbe, San Félix, abril 1996 | Ngöbe Document Volume XII La Chácara — Living Art of the Ngöbe Woman, San Félix, April 1996.

Consumado el matrimonio, la señora se alistó para ir a un río cercano a sacar la pita para hacer una chácara. Por supuesto que Nici se quedó cuidando la casa, mientras la doña se fue con su hija a sacar la pita. Como esta actividad duraba varios días, Nici aprovechó para ir de cacería por la montaña con la intención de encontrarse en alguna parte con los tigres de la suegra y ultimarlos a flechazos.

Mujer Ngöbe extrayendo fibras de Kiga. Documento Ngöbe Tomo XII La Chácara—Arte Vivo de la Mujer Ngöbe, 1996:34 | Ngöbe woman extracting Kiga fibers. Ngöbe Document Volume XII La Chácara — Living Art of the Ngöbe Woman, 1996: 34.

En esa misión se fue a andar por la montaña y, para su sorpresa, se encontró a dos niños en una caverna de piedra, anidando. Cuando los niños se percataron de su presencia, se alegraron y levantaban las manos como queriendo agarrarlo o tocarlo. Primeramente, observó a los dos y vio que ya tenían pelos por sus cuerpos que parecían color de tigre. Además, en las manos tenían piedras de colores de tigres, que estaban modelándolas para convertirse como las manos y uñas de tigres. Él vio que los dos parecían tener arañazos por donde les iban naciendo los pelos. No esperó mucho tiempo y ultimó a los dos con la flecha lo más rápido que pudo y salió corriendo para la casa.

La señora, quien supuestamente estaba sacando las fibras de las pitas en el río, de modo increíble se dio cuenta de lo mismo y corrió para la casa a saber lo que estaba pasando e incluso para darse cuenta también del culpable, aunque ya de antemano sabía que había sido la obra de su ingenuo yerno.

La viejita tenía muchos tigres, que paulatinamente fueron disminuyendo a consecuencia de la matanza que realizaba Nici. A la señora sólo le quedaban dos tigres de los más valientes y de su preferencia y decía que si Nici se atrevía a matar a esos dos, entonces ella si se iba a convencer de la habilidad de Nici como cazador. Esto ella lo repetía cuantas veces quería, con una sentencia y tono desafiante. Los dos tenían características particulares: uno rugía que parecía el sonido de un pedazo de tula chiflada o soplada con aire y el otro parecía tener el canto del Midi, un tipo de ave silvestre.

Pero toda esta amenaza a Nici le parecía poco y ni le daba importancia ya que era una persona hábil quien nunca fallaba una flecha, así que estaba dispuesto al desafío sin importar el momento y lugar. Nici sabía por dónde cruzaban esos dos tigres y un día los aguaitó en su camino. En ese tiempo se usaba para la cacería de tigres un tipo de manto conocido por los guaymíes (ngäbe) como Klee-to, que podía ser un retazo de ropa o un cuero de animal, que se usaba tirado sobre el hombro para jugar y confundir a los tigres.

Siempre Nici llegaba antes de que pasara el tigre. Se preparaba listo con su flecha y Klee-to. Entonces venía una tremenda bulla de animales de todas clases que siempre eran los primeros que pasaban y por último el tigre al que él disparaba con la flecha. El tigre adolorido trataba de agarrarlo con un salto formidable, pero sólo encontraba el Klee-to y allí mismo Nici le disparaba otro certero flechazo acabándolo para siempre.

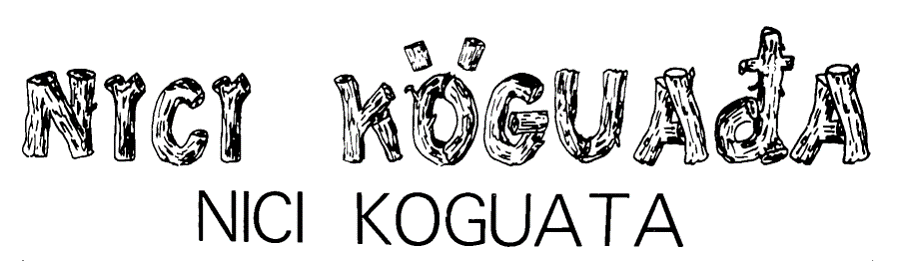

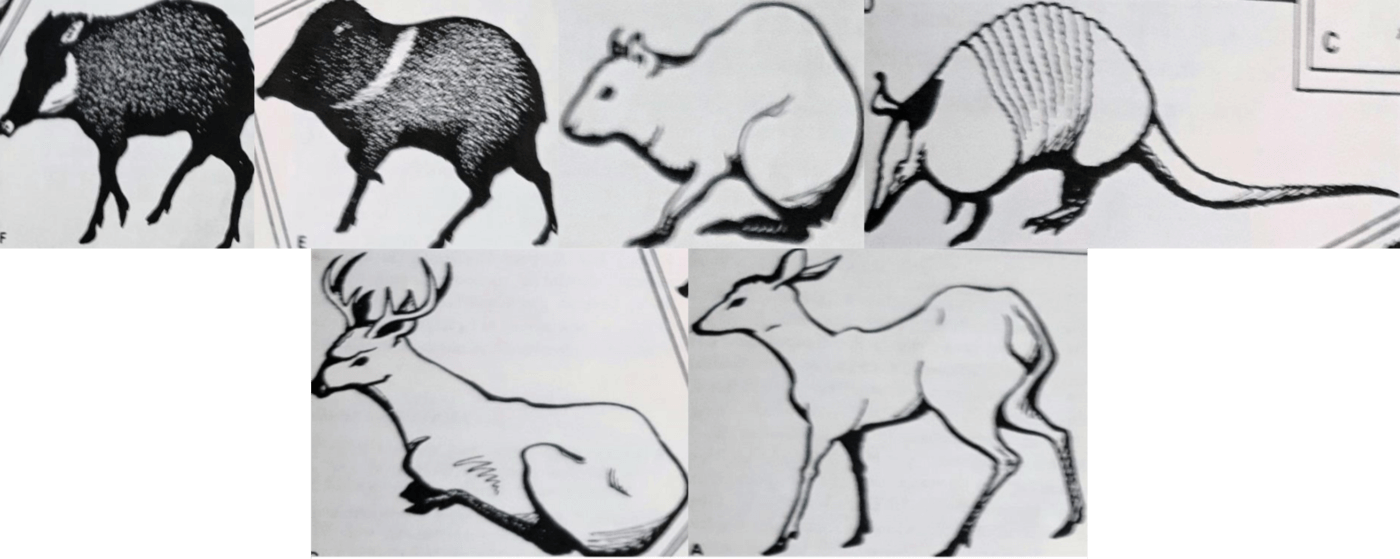

Evolución en los trópicos, Editoras Georgina A. de Alba y Roberta W. Rubinoff, Panamá: Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute y Editorial Universitaria, 1982:265 | Evolution in the tropics, Editoras Georgina A. de Alba and Roberta W. Rubinoff, Panama: Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and Editorial Universitaria, 1982: 265.

Cuando Nici fue a vivir donde la doña, siempre estaba donde el suguiá consultándolo y poniéndolo al tanto de su plan para que no fuera víctima de la brujería de su suegra, ya que ella debía contar con respaldo de otra bruja para vengarse de su enemigo. Por tal motivo, Nici se encomendaba a los suguiás para que no fuera blanco fácil de los tigres, ni de la suegra.

Así Nici planeó matar al tigre que tenía rugido como tula chiflada y se puso en su pasadero como era su costumbre. Como siempre, pasaban otros animales menores adelante del tigre, con su bulla, para permitir más tarde el paso al tigre. Así ocurrió, Nici logró distinguir al zorro, la ardilla, el mono karricho, el gato platanero y una cantidad asombrosa de animales. Por último, venía el enorme tigre que, a cada mínimo ruido, miraba para todos lados en busca de su enemigo o víctima. En el preciso momento que iba pasando al frente de Nici, el tigre pareció recibir la señal de un árbol cargado de bejucos y quedó viendo hacia el árbol. Nici aprovechó la ocasión para dispararle la flecha. Con un formidable salto, el tigre brincó para agarrar a Nici. Éste, con su talento de cazador y la habilidad para desplazarse, sólo dejó el Klee-to en poder del tigre, que lo agarró rompiéndolo en pedazos. El tigre inmediatamente recibió otro soberano flechazo, pero aun así no se murió y se escapó herido de la mano de Nici. Cuando Nici trató de caminar detrás del tigre, oyó una voz que le dijo: “No camine más y regrese para la casa”. Miró y sólo vio en el árbol, entre bejucos, un venado pegado del palo, con la cabeza para abajo. Dada la advertencia, él no quiso seguir más y regresó para la casa.

Cuando él fue a reportarle al suguiá, después de la contienda, que el tigre se había escapado, el suguiá le dijo: “Si hubieras seguido al tigre, ese si te hubiera matado, ya que te estaba esperando en una parte donde usted no iba a distinguirlo y entonces iba a ser presa fácil del mismo”. Es decir, que el venado que vio Nici no era tal venado, sino era el suguiá que se había convertido en venado y estaba allí para proteger a Nici de cualquier imprudencia que le fuera a costar la vida. El tigre se escapó; supuestamente debía estar muerto por la herida que le propinó Nici.

A la viejecita le quedó solamente un tigre. Entonces decidió irse de su casa para otro lugar donde estuviera fuera del dolor de cabeza que le estaba causando Nici.

Ella se fue de la casa, pero Nici le preparó una traición. Ella se fue con el único tigre; lo llevaba cargado al hombro, con los dos ñuños bien agarrados. Llegó a una zanja donde se aprestaba para saltar, con todo y tigre, hacia el otro lado. En ese preciso momento, Nici, quien estaba escondido, reventó la flecha contra el tigre. Éste, con dolor, trataba de ir corriendo, pero la viejecita lo sujetaba contra su cuerpo, no queriendo dejar ir al último tigre. En tanto forcejeo, el tigre la agarró sobre la cabeza con los dientes, convirtiéndola en pedazos, y luego salió huyendo sin rumbo. Así terminó la viejita, que a costilla de los tigres se alimentaba con todo tipo de carne, pero que luego le costó la vida.

Se cree que todos esos gatos eran niños que la viejita se había robado, como los que Nici encontró en una cueva de piedras. Antes, cuando todo era montaña, había brujerías formidables, que los habitantes de la región vivían a expensas de ellas. Se perdían niños de escasas edades y nunca jamás se lograba encontrarlos.

Ecología y Evolución en los Trópicos, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute 2007 | Ecology and Evolution in the Tropics, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute 2007.

Se piensa que algunos de estos niños iban a convertirse, después de muchos años, como tigres, que lejos de ser beneficiosos a sus gentes, constituían un serio peligro para los habitantes, sus animales y crías domésticas. Los niños que las viejas brujas lograban convertirlos como tigres, son los que hacían daños, matando terneros y otros animales silvestres, que luego llevaban para la casa de su dueña como carne de cacería. Entre lo que encontraban había ganado, conejos, venados y otros. Así era la forma en que la suegra de Nici obtenía carne diariamente.

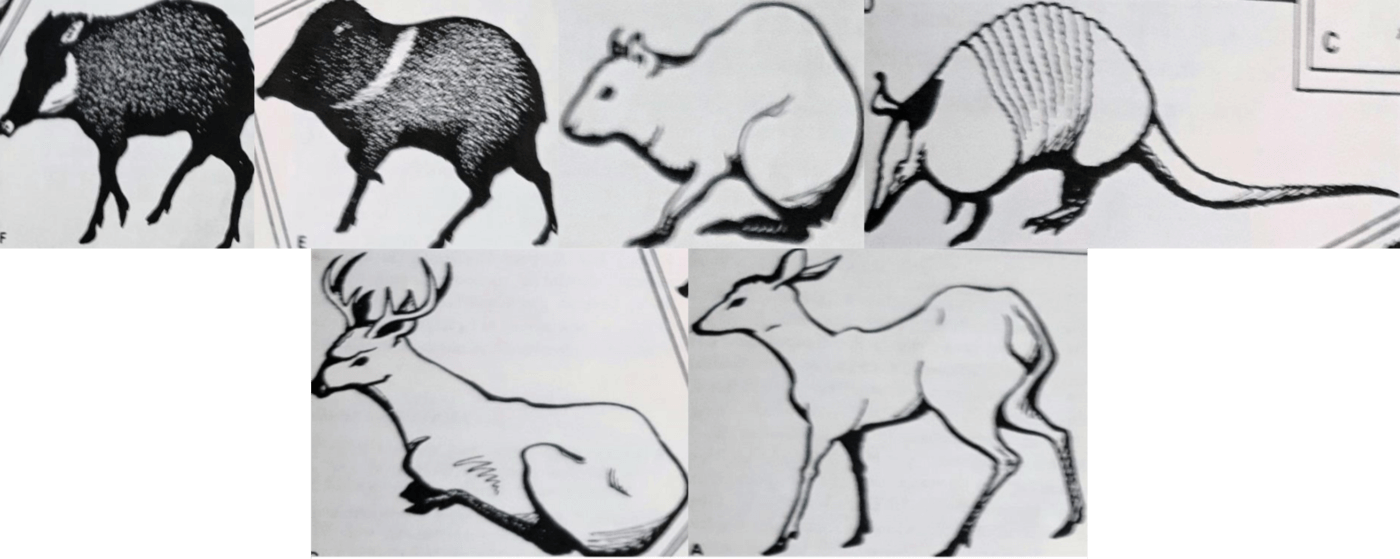

Documento Ngöbe Tomo XII La Chácara—Arte Vivo de la Mujer Ngöbe, 1996:56 | Ngöbe Document Volume XII La Chácara — Ngöbe Woman's Living Art, 1996: 56.

Cuando Nici mató en la cueva a los dos niños e inmediatamente corrió para la casa, lo extraordinario del caso era que en cuestión de momentos ya estaba por allí su suegra, quien precisamente en ese momento debía estar trabajando con las pitas. Él oía a la doña por detrás cuando iba corriendo para la casa y trataba de evadirla cambiando el rumbo y cortando la distancia para llegar más rápido a la casa. Oía la voz de su suegra que decía: “Se fue por aquí, corra por allí, etc…”, hasta que llegó a la casa de un suguiá quien vivía cerca de allí y se metió en la casa. El suguiá inmediatamente lo escondió en su cuarto privado para que la viejita no lo viera.

En cuestión de momentos, apareció la viejita corriendo y fue a parar a la casa del suguiá. Preguntó al suguiá si por allí no estaba Nici y éste le respondió de modo categórico: “¡No!” y que tal personaje él no lo conocía. La doña, que andaba con desesperación, quedó pensativa por un momento, luego se fue. Definitivamente que a ella no la convenció el suguiá, pero tuvo que conformarse con irse para su casa. Cuando ella buscaba incansablemente a Nici era porque ella iba a liquidarlo e incluso a comérselo; pero, gracias al suguiá, no logró conseguirlo. Si ella intentaba a la fuerza conseguir a Nici, se las iba a ver con el mismo suguiá, quien, desde luego, era más poderoso que ella y de todas sus pandillas de brujas.

Cuando Nici mató a los niños y luego la maratón que hizo con su suegra, ésta le quitó la hija inmediatamente, quedando él otra vez sin mujer. Claro que esto no le preocupaba ni en lo más mínimo, ya que no estaba interesado en la mujer, sino en matar a los tigres y dar fin con la doña y acabar con sus prácticas nocivas para los habitantes de la región.

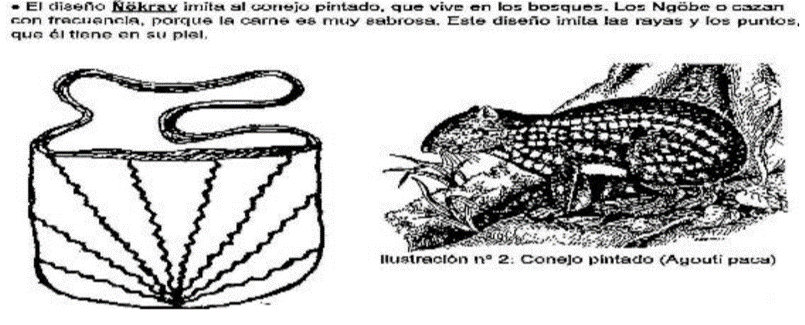

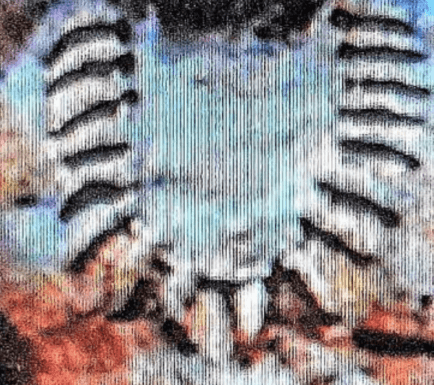

Collar de dientes de tigre usado por los cazadores. | Necklace of tiger teeth worn by hunters.

Después de esto, nadie sabe de la vida de Nici Köguatda. Sólo se sabe que fue un sagaz cazador jamás superado, sobre todo en su combate con los tigres.

Notas del Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo Jiménez

Esta narración tiene como fondo a una señora que se dedica a la cría de tigres, manteniendo su casa como guarida de tigres, que son transformaciones de niños de escasas edades, quienes ella roba y recluta por métodos diabólicos que solamente ella conoce. Luego de algún tiempo de reclutamiento, ella lograba convertir a los niños como tigres que después harían daño a sus propias gentes, dedicándose a las cacerías de animales que encontraban a su paso.

La señora quien llevaba una vida de brujería o de espíritu maligno, se dedicaba exclusivamente a este trabajo. Con esto se da a entender de que todos los tigres que ella tenía eran seres humanos, de escaso tiempo de haber nacido, que milagrosamente los robaba de diferentes lugares y luego los llevaba a la montaña, criándolos en una caverna desconocida, donde muy pocas veces se podía llegar.

La importancia de la narración no estriba en la persona de Nici Köguatda como extraordinario cazador, sino en la vida de la señora como cuidadora de tigres que luego le servían de cazadores y para otros fines que ella consideraba conveniente. Ahora, éstos no son tigres comunes que hay en las montañas y que viven libres, supuestamente, sin ningún dueño en especial y si hacen daño se pueden combatir con poco riesgo. Estos tigres de la narración supuestamente poseen fuerzas diabólicas y son guiados por su dueña, quien es más peligrosa que los mismos tigres. Por tal razón, estos tigres son difíciles de combatir y quien pretenda enfrentarse a ellos corre el riesgo de resultar víctima de los tigres y de su dueña. Esta es la razón por la cual, antes de perseguirlos, se consulta a los suguiás para que los suguiás velen por la vida del cazador en todo momento, al igual que la señora que vela por la vida de sus tigres.

Estos temas de tener espíritu diabólico y tener guarida de tigres son viejos, pero a la vez actuales en ciertas cosas. Los indígenas que vivieron y viven en contacto directo con la selva y la realidad de las montañas, como medio de subsistencia de la vida, creen en varios fenómenos que, según ellos, son posibles y no se pueden tolerar alegremente diciendo que tales cosas son chismes. Los peligros que representan los tigres son reales; pero, aún más serio todavía, según ellos, son los peligros que representan los tigres criados por individuos de espíritu maligno, que no sólo actúan con instinto salvaje, sino que además están guiados por otros espíritus de mayor fuerza.

Resulta difícil la explicación de estos hechos y poderes. Entenderlos no es fácil y sólo lo pueden hacer los indígenas que han vivido y viven completamente identificados con su modo de convivencia en la montaña. Para los individuos quienes son ajenos a esta sociedad, que desconocen el tipo de convivencia dentro de las comunidades indígenas, les puede parecer que estas son creencias fantasmas, falsas brujerías y que en la práctica estas son supersticiones ficticias. Estamos completamente de acuerdo con ellos, porque para entender este tema hay que vivir con los indígenas y entender su modo de vida y, sobre todo, haber nacido con sangre indígena guaymí (ngäbe). De lo contrario, no será fácil de entender para las personas con mente común que están acostumbradas a juzgar a la ligera cualquier cosa y que no están acostumbradas a vivir y sentir lo que sienten y piensan los indígenas, porque los indígenas poseen sus propias culturas, con todas sus implicaciones sicológicas y social propias.

En la narración aparecen cuatro elementos a tomar en consideración: 1. La señora de espíritu diabólico; 2. los tigres, que son seres humanos transformados; 3. un cazador; 4. Un suguiá quien siempre está guiando al cazador por la montaña en la matanza de los tigres.

La presencia de la señora de pronto en la caverna detrás de Nici Köguatda cuando mató a los pequeños individuos que encontró allí, cuando en ese preciso momento ella debía de estar muy lejos de donde él estaba, corrobora que ella poseía poderes malignos como dueña de los tigres que criaba. Estos tipos de personas de espíritu maligno o diabólico, quienes practican la brujería, son considerados como hechiceros en algunos casos. Sin embargo, este vocablo de hechiceros o brujos está muy lejos de la realidad guaymí (ngäbe); pero, en el lenguaje español, es lo más que se puede decir para designar lo que en sí puede significar.

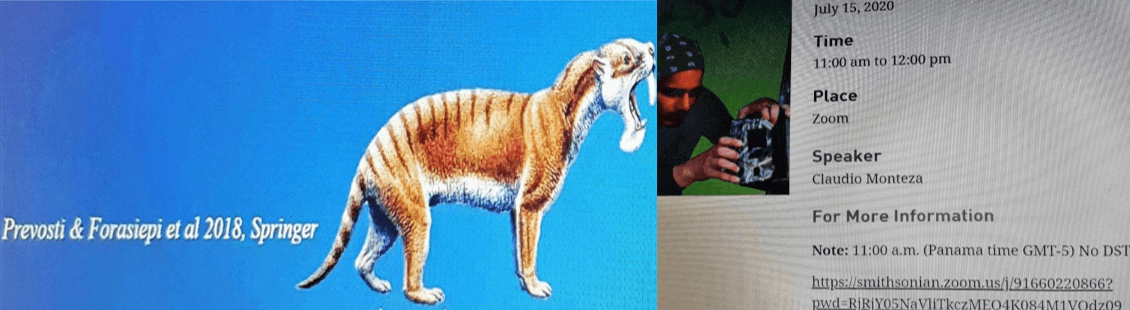

Conferencia del primatólogo Claudio Monteza, vía zoom, sobre los monos capuchinos o cara blanca en la Isla Barro Colorado, República de Panamá, que se han vuelto más terrestres y menos arborícolas porque no hay tigres para cazar a los monos en esta isla | Conference of the primatologist Claudio Monteza, via zoom, about capuchin or whiteface monkeys in Barro Colorado Island, Republic of Panama, that have become more terrestrial and less arboreal because there are no tigers to prey on the monkeys in this island.

Para los guaymíes (ngäbe), ésta no es la mejor designación. En el lenguaje guaymí (ngäbere) existen nombres que realmente designan lo que son estos tipos de personas, a quienes se les conoce como Kórare, Korácire, Nikórage, Ngäbe Kórare. Todos estos términos son completamente guaymíes (ngäbe), cuya raíz “Kora” significa gato o tigre. No es que algunos indígenas sean tigres, sino que se usa este término para llamar a las personas que poseen dogmas malignos o diabólicos. Son pocos los individuos Kórare. No se debe confundir esto con la hechicería ni con magia blanca o negra. Simplemente se debe pensar que, así como hay buenas personas, las hay también malas.

Ecología y Evolución en los Trópicos, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute 2007 | Ecology and Evolution in the Tropics, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute 2007.

Foreword

FOREWORD

To facilitate reading in Ngäbere, we have adapted, with some modifications, the system in the short Ngäbere-Spanish dictionary Kukwe Ngäbere by Melquiades Arosemena and Luciano Javilla, published in 1979 by the Directorate of Historical Heritage of the National Institute of Culture (INAC), now the Ministry of Culture, and the Summer Institute of Linguistics.

It should also be clarified that this story comes from narrators residing in the village of Potrero de Caña, formerly the Tole district of the Chiriquí province, now the Müna district of the Ngäbe Buglé region, from which the Agronomist Roger Séptimo, the compiler and writer is a native. Consequently, the phonology corresponds to the dialectal or regional variation "Guaymí del Interior" (Pacific slope) which differs from the "Guaymí de la Costa" (Caribbean slope of the province of Bocas del Toro and the now district of Kusapin in the Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) in the Guaymí Grammar of Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, published in 1980 by Fe y Alegría. This variant corresponds to what Arosemena and Javilla call "Chiriquí" and which contrasts with the Caribbean variants of Bocas del Toro and the coast of Bocas.

This ethnohistory was published in 1986 in Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere / Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Ethnohistory Guaymí), by the Panamanian Association of Anthropology, with the PN-079 Agreement of the Inter-American Foundation (FIA) managed by Dr. Mac Chapin, Anthropologist, who encouraged us to follow the example he had set by compiling Pab-Igala: Histories of the Kuna Tradition, published in 1970 by the Center for Anthropological Research of the University of Panama, under the direction of Dr. Reina Torres de Araúz.

This book represented the work of the Agricultural Engineer Roger Séptimo, when he was a student in his second year at the Center for Agricultural Teaching and Research in Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, University of Panama (FCAUP), not only writing in Ngäbere the stories that he had heard from his family members in his community, but also his effort to translate them into Spanish as a bilingual person that he is, like other indigenous people in Panama, who are striving to receive a formal education.

The ethnohistories were compiled, recorded on cassettes and written by the Agronomist Roger Séptimo in 1983 and 1984.

As Professor-Researcher of Anthropology and Rural Sociology at the CEIACHI of the FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Anthropologist, Ph.D., encouraged Roger, as one of her students, to write the stories, convince him and show him that she would not exploit or abuse his work, but that he would get credit. Consequently, the anthropologist limited herself only to making some corrections of form and style in the Spanish translations without altering their content.

We encourage students from the seven indigenous peoples in the Republic of Panama, and teachers in public and private schools, colleges and universities in Panama, to write in their own languages and translate the ethnohistories and songs they hear in their families and communities into Spanish, as part of their informal education.

We also encourage readers of these ethnohistories in Ngäbere, Spanish and English, to draw the scenes that they liked the most, as they did in 2002, students in an Education and Society course, directed by Dr. Joly, at the Faculty of Education, Autonomous University of Chiriquí.

Article 13 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, approved by the General Assembly, in its 107th plenary session on September 13, 2007:

- Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, promote and pass on to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to name and maintain their communities, places and people.

- The States shall adopt effective measures to ensure the protection of this right and also to ensure that indigenous peoples can understand and make themselves understood in political, legal and administrative actions, providing for this, when necessary, interpretation services or other appropriate means.

A long time ago, there lived an old woman. She lived alone, away from all her family. Every day she had meats in abundance. People could not explain why, being a woman and alone, she could have so much meat and permanently of hunted animals.

Exposición y cédula en el Museo de Panamá Viejo, foto LGJA 26/07/2019 | Exhibition and identity card in the Museum of Panama Viejo, photo LGJA 07/26/2019.

One day, one of her grandsons, with the interest to really know how it was that his grandmother had so much meat of hunted animals, decided one afternoon to visit his grandmother. It became night when he was in her house; but he did not intent to leave, as he had gone with the intention to stay and not go away until he knew with certainty the reality of the hunts of the old woman. When night fell, the old woman did not know what to do with her grandson and there was no other alternative but to talk to her grandson. The old woman told her grandson to try to urinate the maximum possible and then go to sleep at the loft and at no moment try to come down from the loft during the night. The clever grandson only limited himself to do and fulfill what his grandmother told him and then climbed to the loft.

When the night fell, tigers of all kinds, sizes, and colors started coming to the house from all cardinal points. In the house, there were wooden seats in the form of planks of thick boards, which is very common even today in the guaymi (ngabe) regions. These seats formed a circle inside the house, that at first surprised the boy who could not understand how was it possible that the old woman, who usually did not receive visitors, could have so many seats in the house. For whom or for what were those seats, the grandson asked himself. This doubt slowly began to clear and leave his mind.

Lying in the loft looking through the cracks in the of bamboo or pieces of bark of the pixbae palm, he saw the tigers arrive and accommodate themselves immediately in a file on the seat. Others that arrived would be lying on the bed of the old woman; that is to say, these were the preferred ones of his grandmother, and she would caress them as if she would be caressing domestic cats. Some arrived with hunted animals of different kinds.

Radical Distilling, Tierras Altas, Panamá 2017 | Radical Distilling, Highlands, Panama 2017.

He was observing all that was occurring below. Now knowing for whom were the seats, he limited himself only to move on the bed up in the loft. With the noise, the tigers would roar at the same time and would place themselves in a position to leap and attack. The old woman would tap them on their heads with her hands, trying to calm the tigers. In this way the night went on until the daybreak.

When the day broke, the tigers left one by one in a file and left the house until it was completely empty. Then he came down from the loft already convinced to have achieved his investigation.

The old woman said to him: “Please do not comment anything of what you saw here and do not tell anyone; this is a private secret of my possession.”

But, as always, there is nothing that is not commented, be it sooner or later, as nothing gets occult, because there will always be a person who will not let much time go by to tell the things. The grandson went running to his house and, with awe, commented what he had seen, without paying heed to the advice of his grandmother.

In those days there lived an extraordinary hunter known as Nici Köguatda, who became aware of the same thing and immediately tried to know the woman and find out if she had a daughter. Exactly, the old woman had a daughter who apparently did not live with her. Nici went to the house where the old woman lived and asked her to give him her daughter to be his wife. Sons-in-law of the woman and other individuals, with the eagerness to get rid of the old woman because of her witchcraft, recommended Nici, telling the old woman that he was a formidable hunter and an extraordinary man and that she would not have any problems, but that he would be at her service and take care of her maintenance. At first, the old woman did not seem to like this idea and did not accept Nici´s proposal, nor that of his friends.

La botánica y la historia natural de Panamá: La Botánica e Historia Natural de Panamá. Editores William G. D´Arcy Jardín Botánico de Missouri y Mireya D. Correa A. Universidad de Panamá. Saint Louis, Missouri, Jardín Botánico de Missouri, EE. UU., 1985 | The Botany and Natural History of Panama: La Botánica e Historia Natural de Panamá. Editores William G. D´Arcy Missouri Botanical Garden y Mireya D. Correa A. Universidad de Panamá. Saint Louis, Missouri, Missouri Botanica Garden, USA, 1985.

But Nici indefatigably persisted in his desire. After so much telling her, he convinced the old woman, and she gave him her daughter. Nici´s insistence was no more than a maneuver to find out the witchcraft that the old woman practiced and seek some way to finish it. It was not so much the desire to marry the daughter of the old woman, nor the wish to serve her, but of wanting to kill all the tigers that the old woman had under her power, as these were the ones that did harm, eating all the calves that lived in the valleys.

Documento Ngöbe Tomo XII La Chácara—Arte Vivo de la Mujer Ngöbe, San Félix, abril 1996 | Ngöbe Document Volume XII La Chácara — Living Art of the Ngöbe Woman, San Félix, April 1996.

After the marriage was accomplished, the old woman got ready to go to a nearby river to cut kiga (in ngabere, pita in Spanish, Ananas magdalenae or Achmea magdalenae André) to make bags. Of course, Nici stayed taking care of the house, while the old woman and her daughter went to cut kiga. As this activity would take several days, Nici took advantage of this to go hunting in the mountains, with the intention to find somewhere the tigers of his mother-in-law and kill them with his arrows.

Mujer Ngöbe extrayendo fibras de Kiga. Documento Ngöbe Tomo XII La Chácara—Arte Vivo de la Mujer Ngöbe, 1996:34 | Ngöbe woman extracting Kiga fibers. Ngöbe Document Volume XII La Chácara — Living Art of the Ngöbe Woman, 1996: 34.

In that mission, he went to walk to the mountain; and, for his surprise, he found two boys nesting in a rock cave. When the boys became aware of his presence, they got happy and lifted their hands as if wanting to grab or touch him.

First, he observed the two and saw that they had in their bodies hairs that seem the color of tigers. Moreover, in the hands they had stones of the colors of tigers, that they were forming them to convert them as the paws and fingernails of tigers. He saw that the two seemed to have scratches from which were growing hairs. He did not wait much time and killed the two with an arrow the fastest he could and left running for the house.

The old woman who supposedly was extracting fibers from the kiga by the river, in an incredible way became aware of the same and ran to the house to know what was happening and also know who was the culprit; although, beforehand, she already knew it was done by her candid son-in-law.

The old woman had many tigers, that gradually were diminishing as a consequence of the killings done by Nici.

The old woman had only two tigers left, of the most fierce ones and of her preference; and, she said that if Nici dare kill these two, then she would be convinced of the ability of Nici as a hunter. She would say this as many times as she wanted, in a menacing and defiant tone. The two tigers had particular characteristics: the roar of one was like the sound of a piece of whistling gourd or blown with air and the other sounded like the song of the Midi, a type of wild bird.

But all these menacing threats did not seem much to Nici and he did not even give them importance as he was a very skillful person who never failed with an arrow, so he was willing to meet the challenge at any time and place. Nici knew where those two tigers crossed the trail and one day, he went to watch them by the trail. In those days, to hunt tigers, men used a cloak known by the guaymí (ngäbe) as a Klee-to, that could be a piece of cloth or the skin of a animal, that would be used over a shoulder to play with and confuse the tigers.

Nici would always arrive before the tiger would pass by. He would be ready with his arrow and Klee-to. Then there would be a tremendous noise of animals of all classes that always were the first ones to pass by; and, last of all, came the tiger to which he would throw the arrow. The wounded tiger would try to grab him with a formidable jump but would only get hold of the Klee-to and right then Nici would shoot another well-aimed arrow getting rid of the tiger forever.

Evolución en los trópicos, Editoras Georgina A. de Alba y Roberta W. Rubinoff, Panamá: Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute y Editorial Universitaria, 1982:265 | Evolution in the tropics, Editoras Georgina A. de Alba and Roberta W. Rubinoff, Panama: Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and Editorial Universitaria, 1982: 265.

When Nici went to live in the house of the old woman, he would always be consulting a suguiá (diviner and advisor in the ngäbe socio culture), letting him know of his plans so that he would not be a victim of the witchcraft of this mother-in-law, as she was backed by another witch to avenge her enemy. For that reason, Nici would seek the protection of the suguiás, so that he could not be an easy prey of the tigers, nor of his mother-in-law.

Thus Nici planned to kill the tiger that roared like a whistling gourd, and he placed himself in the path as he usually did. As always, smaller animals passed before ahead of the tiger, with their noise, to allow the tiger to pass after. That´s how it happened; Nici could distinguish the wolf, the squirrel, the whiteface monkey, the plantain cat, and an amazing number of animals. Last of all came the enormous tiger that, at the most minimum sound, would look everywhere in search of his enemy or victim. At the precise moment that it was passing in front of Nici, the tiger seemed to perceive a sign in a tree full of vines and it stopped looking to the tree. Nici took advantage of this opportunity to shoot an arrow. With a formidable leap, the tiger jumped to grab Nici. With the talent and ability as a hunter to move rapidly, he left the Klee-to in the paws of the tiger, that grabbed it and tore it in pieces. The tiger immediately received another sovereign arrow; but, even so, did not die and escaped wounded from the hands of Nici. When Nici tried to follow the tiger, he heard a voice that said: “Don´t go any further and return home.” Nici looked and only saw in the tree, among the vines, a deer attached to the trunk, with his head downwards. Given the warning, he did not go any further and returned to the house.

When he went to report to the suguiá, after the encounter, that the tiger had escaped, the suguiá told him: “If you would have chased the tiger, it would have killed you, as it was waiting in a section where you would not have noticed it and then you would have been an easy prey of it.”

It means that the deer that Nici saw was not a deer, but it was the suguiá who had transformed into a deer and was there to protect Nici of any imprudence that what have cost his life. The tiger escaped; supposedly, it should have been dead because of the wound that Nici caused it.

The old woman had only one tiger left. Then she decided to leave her house and go to another place where she would not have the headache that Nici was causing her.

She left the house, but Nici prepared her a treason. She went with the only tiger that she had left; she carried it on her shoulders, with both paws well tied. She got to a ditch where she was ready to jump, tiger and all, to the other side. At that precise moment, Nici, who was hiding, shot an arrow to the tiger. With pain, it tried to run, but the old woman pressed it against her body, not wanting to lose the last tiger. In that struggle, the tiger got her head with its teeth, tearing her into pieces, and then ran away without a route. Thus was the end of the old woman, who, at the expense of the tigers, would feed herself with all kinds of meats; but after, it cost her life.

It is believed that all those tigers were children who the old woman had stolen, as the ones Nici had found in the rock cave. Before, when all was mountainous, there were formidable witchcrafts, that the inhabitants of the region lived at their expense. Children of early ages were lost and could never be found.

Ecología y Evolución en los Trópicos, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute 2007 | Ecology and Evolution in the Tropics, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute 2007.

It is thought that some of these children would be transformed, after some years, into tigers, that, far from being beneficial to their people, became a serious danger for the inhabitants, as well as their wild and domestic animals. The children whom the old witches transformed into tigers, were the ones that were dangerous, killing calves and other wild animals, that then would take to the house of their owner as hunted meat. Among those could be found cattle, rabbits, deer, and others. That was the way in which Nici´s mother-in-law obtained daily meat.

Documento Ngöbe Tomo XII La Chácara—Arte Vivo de la Mujer Ngöbe, 1996:56 | Ngöbe Document Volume XII La Chácara — Ngöbe Woman's Living Art, 1996: 56.

When Nici killed the two boys in the cave and immediately ran to the house, the extraordinary thing of this case was that in a few moments his mother-in-law arrived, who precisely at that moment she should have been working with the pita. He could hear the old woman behind him as he was running to the house and would try to avoid her changing his route and cutting distance to get faster to the house. He could hear the voice of his mother-in-law saying: “He went this way, run over there, etc.”, until he got to the house of a suguiá who lived nearby and got into his house. The suguiá immediately hid him in a private room so that the old woman could not see him.

In a matter of moments, the old woman appeared running and went to the house of the suguiá. She asked the suguiá if Nici was around there and the suguiá answered categorically: “NO!” and that he did not know such a person. The old woman, who was desperate, remained thoughtful for a moment, and then left. Definitely, she was not convinced by the suguiá, but had to conform herself to return to her house. When she was desperately trying to find Nici, it was because she wanted to kill him and even eat him; but, thanks to the suguiá, she could not find Nici. If she would forcefully try to get Nici, she would have had to face the suguiá, who, of course, was more powerful than her and all her gangs of witches.

When Nici killed the boys and the marathon that he made with his mother-in-law, she immediately took her daughter away from him, leaving him without a wife. Of course, this did not worry him in the least, as he was not so much interested in a wife, but in killing the tigers and put an end to the old woman´s evil practices towards the inhabitants of the region.

Collar de dientes de tigre usado por los cazadores. | Necklace of tiger teeth worn by hunters.

After this, nobody knows about the life of Nici Köguatda. It is only known that he was a clever hunter never surpassed by anyone else, especially in this combat with the tigers.

Notes by Agricultural Engineer Roger Séptimo Jiménez

This narrative has as a background a woman who dedicated herself to raise tigers, becoming her house a den of tigers, that are transformations of children of early ages, whom she steals and recruits by diabolic methods that only she knows. Sometime afterwards, she transforms the children into tigers that then become a danger for their own people, dedicating themselves to hunt animals that they find on their path.

The woman, who led a life of witchcraft or of an evil spirit, dedicated herself exclusively to this work. With this, it is understood that all the tigers that she had were human beings, of a few times after their birth, whom she stole miraculously from different places and then would take them to the mountain, rearing them in an unknown cave, where very few times one could get there.

The importance of this narrative is not in the person of Nici Köguatda as an extraordinary hunter, but in the life of the old woman as caretaker of tigers that after would serve her as hunters and for other things that she considered convenient. Now, these are not common tigers that live in the mountains and that are free, supposedly, without any special owner and, if they do harm, it can be combatted with little risk. These tigers in the narrative supposedly possess diabolic strength and are guided by their owner, who is more dangerous than the tigers themselves. For that reason, these tigers are difficult to combat and whoever pretends to face them runs the risk of becoming victims of the tigers and of their owner. This is the reason why, before chasing them, the suguias are consulted so that the suguias can look after the life of the hunter at all moments in the same way that the old woman looked after the life of her tigers.

These themes of diabolic spirits and having a den of tigers are old, but at the same time are current in certain things. The Indians who lived in the past and nowadays live in direct contact with the jungle and the reality of the mountains, as a means of subsistence in living, believe in various phenomena that, according to them, are possible and cannot be happily tolerated saying that such things are gossips. The dangers that represent the tigers are real; but, even more serious, according to them, are the dangers represented by the tigers reared by individuals of evil spirit, who not only behave with savage instincts, but also are guided by other spirits of greater forces.

It is difficult to explain these facts and powers. It is not easy to understand them and can only be understood by the Indians who have lived and live completely identified with their way of survival in the mountains. Individuals who are strangers to this society and do not know the type of living within indigenous communities, may think that these are phantom beliefs, false witchcraft, and that in the practice these are false superstitions. We are completely in agreement with them, because in order to understand this theme one has to live with the Indians and understand their way of life and, above all, have been born with guaymi (ngäbe) Indian blood. On the contrary, it will not be easy to understand by persons with a common mind and who are accustomed to judge lightly anything and who are not accustomed to live and feel what Indians feel and think, because the Indians possess their own cultures, with all their own psychological and social implications.

In the narrative there appear four elements to take into account: 1. the woman of diabolic spirit; 2. the tigers who are transformed human beings; 3. a hunter; 4. a suguiá who was always guiding the hunter in the mountain in killing the tigers.

The presence of the old woman so soon in the cave behind Nici Köguatda when he killed the small individuals whom he found there, when in that precise moment she should have been far away from where he was, corroborates that she possessed evil powers as owner of the tigers that she raised. These types of persons of evil spirit, who practice witchcraft, are considered to be witches in some cases. Nevertheless, this word of witch or wizard is far from the guaymi (ngäbe) reality, but in the Spanish or English languages, this is the most that can be said to designate what it could mean.

Conferencia del primatólogo Claudio Monteza, vía zoom, sobre los monos capuchinos o cara blanca en la Isla Barro Colorado, República de Panamá, que se han vuelto más terrestres y menos arborícolas porque no hay tigres para cazar a los monos en esta isla | Conference of the primatologist Claudio Monteza, via zoom, about capuchin or whiteface monkeys in Barro Colorado Island, Republic of Panama, that have become more terrestrial and less arboreal because there are no tigers to prey on the monkeys in this island.

For the guaymí (ngäbe), this is not the best designation. In ngäbere, (the guaymi or ngäbe language) exist names that really designate what these types of persons are, who are known as: Kórare, Korácite, Nikórage, Ngäbe Kórare. All these words are completely guaymi (ngäbe), from the root “Kora” that means cat or tiger. It is not that some Indians are tigers, but the word is used to call persons who possess evil or diabolic dogmas. There are few Kórare individuals because very few times can be learned to be Kórare. This cannot be confused with witchcraft nor with white or black magic. One simply has to think that, as there are good people there are also bad ones.

Ecología y Evolución en los Trópicos, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute 2007 | Ecology and Evolution in the Tropics, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute 2007.

Kira viyo nomlen nünen caibe nguarabe. Nünen caibe amatibe ngrí ere käre kue güi merire amatibe. Boräi bati tö manlin nain kondi köböti abogo gain. Ñó amatibe ngrí ere käre kue. Abogo erere nigalin kontdi basare ie. Ningalin dere, kontdi, kä jatalin dere biti möle gondi. Ñan tö namanlin nainda jajiöbiti. Ne nigalin ñó gore amlen. Guiere noen nom-len mölegüe. Ñó amatibe ngrí ere käre kue güi, ne nomlen kuen ñó ie.

Exposición y cédula en el Museo de Panamá Viejo, foto LGJA 26/07/2019 | Exhibition and identity card in the Museum of Panama Viejo, photo LGJA 07/26/2019.

Abogo tö namanlin gai, nigalin mie ñäräre. Kä jatalin dere amlen viyogüe jualin kuin amlen intranin gamlam krií biare ie mölegüe. Ñan nangraman ie dibire. Krere bare kue biti juanlin jonteri kuin kä jatalin igo amlen kóra bötägä be nguarebe jatalin nöbre nguägare. Amlen güi krikuata krií migalin ja tägräre ngötaibe ta güi. Basagä ñagare ie amatibe jatägrä krií diare kue güi. Amlen ñara nomlen nünen kaibe arato amatibe. Boräi nomlen jonteri kuin abogo nigren jon mogäde ta, guiere rögaigä abogo nguibiare. Kóra jatalin nöbre guägäre nigalin ja üguete kri ngrabre oguä biti.

Ñaragüe ja kuitade kuin jonbiti amlen kóra namanlin mäträ ngö miguegä, abogo bata ñara namanlin nebeta kueguebe.

Bätägäbe nguarebe jatalin nöbre guägäre ngrí guetalinte tude roäre.

Radical Distilling, Tierras Altas, Panamá 2017 | Radical Distilling, Highlands, Panama 2017.

Roäre nigalin kitede viyo bata temen jonbiti; ni nügue minyi bäsögue ngrabre sete krere viyo namanlin bäsögue oguäbiti. Ñara namanlin ja kuitede kuin amlen kóra namlin mäträ ngö miguegä abogo bata namlin nebeta kueguebe am´len viyo namanlin mede doguägä bata, migueta kueguebe. Boräi töí be namanlin dibire kuin biti kä jatalin ngüen degä. Kä jatalin ngüen amlen kóra nigalinta nöbreta jibiti, nigalinta jogrä amlen jatalin timon. Viyo güe ñägäbare ie: ne mañan tönguan kädriere, magüe ñan kädrie, niebare ie akua madare krere, kugüe ñó madare nguä rabara kädriebare, rabara ngalin sete krere nögalingä. Nin kugüe neguetalin bata nigalin betégätda ja gríete, ñó erere kädriebare tütde kue. Ne näire amlen Nici Köguatda nomlen nünen arato kägüe ngalin. Ñara abogo brai krií, mundiare valiende: bugöbiti dröräbiti. Nigalin ja krüguenen jötrö nguarabe viyobe. Viyo abogo ngongä nomblera kaibe arato. Abogo Nici Kö- 6 guatda nigalin kärere ie. Ne ñó tdari amlen tö namanlin gräguitai jabata viyobe, amlen kórabe arato. Viyo güe ngalin jabata grere akua namanlin kueguebe. Kena nin namanlin Nici kugüe migue era: Nici namanlin ja brai krií niere ie, jagüe muntiadi krägä, bugö nebe ñagare metre jaigua, jagüe mundiadi kiaguia kräga, namanlin niere viyo ye. Namanlin jamigue bobre diaro. Mra viyo ngalainbare kue.

La botánica y la historia natural de Panamá: La Botánica e Historia Natural de Panamá. Editores William G. D´Arcy Jardín Botánico de Missouri y Mireya D. Correa A. Universidad de Panamá. Saint Louis, Missouri, Jardín Botánico de Missouri, EE. UU., 1985 | The Botany and Natural History of Panama: La Botánica e Historia Natural de Panamá. Editores William G. D´Arcy Missouri Botanical Garden y Mireya D. Correa A. Universidad de Panamá. Saint Louis, Missouri, Missouri Botanica Garden, USA, 1985.

Viyo güe ngöngä bialin ie. Nebiti viyo niganlin kía tdigue mada amlen ñara namanlin jubäre, namanlin jakrüguene ju nguiabiagä aicete migalinte jubäre, jurügüe. Jamigalingä arato kue jubäre ñó gäre amlen tö namanlin nain kätoguä nguäre mundiare. Erere niganlin, konti ngäbägre bütiegro ngualin nibu jämogäte kätöguate ie, ngäbägre kía kualin nibu ie jämagäte düren jatalinna ngrabre kóra düren krere. Jä tóare nomlen mialin kise teri bä kóra bä krere nomlen mialin kisetde biti kise kualintde kue, kusugä jatalinna kóra krere bä jatalin tóare ngranbre jäbä krere. Namlin köböre nguarabe ngäbägre ye akua ñaragüe ngäbägre kämigalin (Mure kentalin). Viyo abogo nomlen kía tdiguen kägüe ngalin jatalintda ie güa, jatalin nen ie guä konti nigalin nigüite jabata konti viyo nigalin kóra noinare kue erere nigalin köbämigue ie. Kontdi dönlon nomblen kóra kraire jiete kontdi nomblen tägue Bugobiti, kóra nomlen kratií viyo tdüe Nici nomlen kämigue kätöguä nguäre nomlen ja tuen ben nguanre, mundiabata. Abogo krere bata kóra bäri krüguäge aibe jatalin nebengo mrä viyo güe. Nici jatalin kämigue jogrä.

Documento Ngöbe Tomo XII La Chácara—Arte Vivo de la Mujer Ngöbe, San Félix, abril 1996 | Ngöbe Document Volume XII La Chácara — Living Art of the Ngöbe Woman, San Félix, April 1996.

Kóra namanlin krobütde viyogüe, bäri krüguabe, amlen bäri tare kue. Kugüe mrüoto gugüere, midi gugüere. Abogo viyo namanlin käbä migue mada Niciye. Kugüe krörö ne magüé kämiguei amlen tigüe ma miguei ütiäte jai, ma migue, era nie namanlin ie viyo güe bäre bäre. Nici Köguatda abogo nomlen tebaire ñagare, bugo nebe ñagare temen ie aicete käi tare ñagare oguäta nomlen kraire jiete. Nomlen nebe kóra graire jiete kleeto nguitalin gäre.

Kóra nomlen kite biti nomlen tägue bugo biti kóra nomlen ja täguete biti kain jakälin ñara nomlen niguen betegä kleeto ve migatde nomlen kue abogo ve kóra nomlen kain, ñara abogo nomlen nguitie kuäräbe.

Kóra bäri krüguabe namanlin viyo güe krobutde abogo käbä migalin kue Nici ie. Nici güe kugüe mrüotdo gugüere kraibare jiete.

Mujer Ngöbe extrayendo fibras de Kiga. Documento Ngöbe Tomo XII La Chácara—Arte Vivo de la Mujer Ngöbe, 1996:34 | Ngöbe woman extracting Kiga fibers. Ngöbe Document Volume XII La Chácara — Living Art of the Ngöbe Woman, 1996: 34.

Ne abogo Nici nomlen kädriere nierara suguiabe, ne krere ñan noemdre kue viyogüe kuatai kóra doguäre. Viyo ne abogo kórare krií, ribanga kórare krígri neguete kuatiíben. Nici abogo nomlen köböi gärere suguia ye biti nomlen kraire jite. Ne krere nomlen nuenne käre. Nomblen kraire jiete amlen jondron bätäbe nguarabe nomblen kite kälin: mubia, doraci, cotän, rürübäm jie nguangä abogo jiöbiti mrä nomblen kite. Kä ngä rabaga ñan ngüe migra jogrä jabata kuariguäri kue. Ne krere abogo kugüe mrüotdo gugüere tägälin kue, abogo murio nigalin jabare niguen jiöbiti amlen ñan nän niebare ie ben nigrabare kue amlen büra tain (krocito) kuekebe nabalingä doguä timonguälen krigüdetde kuin käguë ñägäbar ie. Ne ye guidianre jabata, abogo bata suguia nomlen krigüdetde kägüe ñägäbare ie. Ne krere ñan noendre kue ne ye guidiandre. Abogo bata nigalinta jiriäbe nguä niereta suguia ye.

Evolución en los trópicos, Editoras Georgina A. de Alba y Roberta W. Rubinoff, Panamá: Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute y Editorial Universitaria, 1982:265 | Evolution in the tropics, Editoras Georgina A. de Alba and Roberta W. Rubinoff, Panama: Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and Editorial Universitaria, 1982: 265.

Niebareta kue suguia ye amlen kägüe niebare ie, ye marigadre jäglun jiöbiti yeye ma guidiandre niebare kue ie. Namanlin krátibe kugüe midi gugüere ai be amlen viyo nigalin nguitie ben kä madabiti, küde dialin kätäbita kue nomlen ngüen nabalin ngurumbata amlen viyo namanlin ja nuentde nanguandregä ta kórabe, ngöi. Nomlen ja nuende nanguandregä amlen Nici güe kóra tägälin tröbata. Bugo namanlin tare kóra ye kä namanlin ja kriengä mentdongälen, tö namnlin nguitiai amlen viyo namanlin bäri küde ketetde dime kisetde, namanlin ja di nuen kórabe mrä, te kä nigüitanlinga kórabiti kägüe calin doguäbiti. Doguä tregalintde kóragüe kontdi kämigalin kóragüe, ne krere ñan noendre kue abogo krägä ni kóragüe kämigadre jötrö nguarabe näre abogo namanlin bare.

Kóra kämiga nomlen Nici köguatdagüe ne abogo ngäbägre be jogrä, ne abogo ni nire be jogrä. Ngäbägre butiegra kía goi nomlen jikrati viyo güe abogo nomlen kuite kórare abogo nomlen kue. Kira amlen kätoguä be jogrä ngäbägre nomlen nentde krügüate, ni nünangä ñagare bogän amlen kätögä krií, temen aicete ngäbägre nomlen nentde nomlen nen käbe tari, nin nomlen kuentdari. Nomlen kuitde kórare ne abogo nomlen gore miguibiti temen, nivi güetegore ngäbegän abogo ngrie tiga nomlen bata: ñä ngríe, büra ngríe nivi ngrie tdiga, guägäre kóragüe ie ne krere kuete abogo guisete kä ngrire käre kue. Ne abogo guisete kä ngrire käre kue abogo ñan nomlen nügue gare.

Ecología y Evolución en los Trópicos, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute 2007 | Ecology and Evolution in the Tropics, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute 2007.

Nici Köguatda güe ngäbägre bütiegra kämigalin jämogätde amlen viyo abogo nigalin kía digue ñöbata, viyo abogo kórare krií aicete ngalinbe arato kue, ngö nügalinrabe kontdi. Ne nguanlen abogo tädre kía tigue bä amatibe.

Nici güe ngäbägre kämigalin amlen nigalinrabe nguitietda ngägrä suguia gontdi, viyo ngonlienre. Nigalin vetegä amlen ni gugüe naman-linrabe jiöbiti arato. Niguï nere ye ni gugüe namanlin neve jiöbiti amlen ñara namanlin miguebiti ta, mrienbiti ta. Niguí nere ye ni gugüe namanlin neve jiöbiti amlen ñara namanlin miguebiti ta, mrienbiti ta. Negui nere ye ni gugüe rabata jiöbiti. Namanlinra kuatanguarabe amlen nigalin vetegä nguägäre suguia ye, kontdi nguitialin suguia ya guä. Amlen viyo naman-lin rabe vetegä guägäre jiöbiti.

Documento Ngöbe Tomo XII La Chácara—Arte Vivo de la Mujer Ngöbe, 1996:56 | Ngöbe Document Volume XII La Chácara — Ngöbe Woman's Living Art, 1996: 56.

Ni gä kröro ñagare nere ya niebare kue suguia ye. Nan amlen suguia güe Nici ügalin käteri jai ñara ngonlienre.

Kontdi ja nam-len kuitegä, jatalintda ja jiöbiti. Nin migalin era kue grere gua viyo kórare krií aicete ne galin kue grege kua suguia bata jatalinta jiriäbe jajiöbiti. Ne krere ñan noemdre Nici güe abogrä reguetaite ie, kuátadre kue ngäbägre bütiegrä dogäre. Nguitialin suguia ngontdi abogo bata toalin oguäre kue.

Nici güe ngäbägre bütiegrä kämigalin viyo ngän amlen namanlintda kaibe, viyo güe ngongä dialingätda kän kue.

Collar de dientes de tigre usado por los cazadores. | Necklace of tiger teeth worn by hunters.

Dönlön güe ngäbägre bütiegrä kämigalin kän doguare, kóra ngäbäli kämigalin kän ne abogo doguare dätebareta kaibe kue. Dönlön naman-linta kaibe ne abogo ñan tebaibare kue amlen. Tö namanlin ngüarabe kugüe noen ne, ñan nomlen nain meri tari amlen tö naman-lin kóra viyo güe kämigue abogo tari nom-len ja krüguene viyobe. Rebei kaibe ñó kärera. Naman-lin kaibe bäri namanlin kóra ngämigue krüguatde.

Conferencia del primatólogo Claudio Monteza, vía zoom, sobre los monos capuchinos o cara blanca en la Isla Barro Colorado, República de Panamá, que se han vuelto más terrestres y menos arborícolas porque no hay tigres para cazar a los monos en esta isla | Conference of the primatologist Claudio Monteza, via zoom, about capuchin or whiteface monkeys in Barro Colorado Island, Republic of Panama, that have become more terrestrial and less arboreal because there are no tigers to prey on the monkeys in this island.

Nici Koguatda güe kämigalin jogrä, viyo kämigamlan kue kóra naman-lin kratdibe mrä ie, nebiti jraimbare abogo gare ñagare tari.

Kä gädianta käguatabiti matdare abogo tä nebengo Mredra ngüdebiti. Sulia guatabiti mindonguänlen. Kä ne ve abogo kä krörö abogo bata ni ne abogo kä ne ngontdi nieta akua ne erere ya abogo gare ñagare tari.

Jraimbare ñó gare ñagare metdre. Rübare kue jürübe kue aibe gare, kä ñóngonlen nünambare kue gare ñagare arato.

Ecología y Evolución en los Trópicos, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute 2007 | Ecology and Evolution in the Tropics, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute 2007.