MIRONOMBOS y CRONOMBOS convirtieron a METOBOS en piedras y árboles. A la izquierda foto de piedra tallada en la Reserva Guaimí de Alto Laguna, Sur de Costa Rica. A la derecha árbol en finca privada en Colón. | MIRONOMBOS and CHRONOMBOS turned METOBOS into stones and trees. On the left photo of carved stone in the Guaimí Reserve of Alto Laguna, South of Costa Rica. On the right tree in a private farm in Colón.

Prólogo

PRÓLOGO

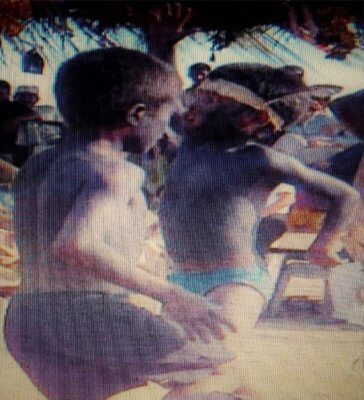

Para facilitar la lectura en ngäbere, hemos adaptado, con algunas modificaciones, el sistema en el breve diccionario ngäbere-español Kukwe Ngäbere de Melquiades Arosemena y Luciano Javilla, publicado en 1979 por la Dirección del Patrimonio Histórico del Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INAC), ahora Ministerio de Cultura, y el Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

También conviene aclarar que esta historia proviene de narradores residentes en el corregimiento de Potrero de Caña, antes distrito de Tole de la provincia de Chiriquí, ahora distrito de Müna de la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé, de donde es oriundo el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, el recopilador-escritor. Por consiguiente, la fonología corresponde a la variación dialectal o regional “Guaymí del Interior” (vertiente del Pacífico) y que difiere del “Guaymí de la Costa” (vertiente caribeña de la provincia de Bocas del Toro y del ahora distrito de Kusapin en la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) en la Gramática Guaymí de Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, publicada en 1980 por Fe y Alegría. Esta variante corresponde a la que Arosemena y Javilla denominan “Chiriquí” y que contrasta con las variantes caribeñas de Bocas del Toro y costa de Bocas.

Esta etnohistoria fue publicada en 1986 en Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere/Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Etnohistoria Guaymí), por la Asociación Panameña de Antropología, con el Convenio PN-079 de la Fundación Inter-Americana (FIA) gestionada por el Dr. Mac Chapin, Antropólogo, quien nos animó a que siguiéramos el ejemplo que él había sentado al recopilar el Pab-Igala: Historias de la Tradición Kuna, publicadas en 1970 por el Centro de Investigaciones Antropológicas de la Universidad de Panamá, bajo la dirección de la Dra. Reina Torres de Araúz.

Este libro representó la labor del Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, cuando era estudiante en su segundo año en el Centro de Enseñanza e Investigación Agropecuaria de Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad de Panamá (FCAUP), no solo de escribir en ngäbere las narraciones que había oído relatar a sus familiares en su comunidad, sino también su esfuerzo de traducirlas al español como persona bilingüe que es, al igual que otros indígenas en Panamá quienes se esfuerzan por recibir una educación formal.

Las etnohistorias fueron recopiladas, grabadas en casetes y escritas por el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo en 1983 y 1984.

Como Profesora-Investigadora de Antropología y Sociología Rural en el CEIACHI de la FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Antropóloga, Ph.D., animó a Roger, como uno de sus estudiantes, a escribir las historias, convencerlo y demostrarle que no explotaría ni abusaría de su trabajo, sino que se le reconocería su mérito. Por consiguiente, la antropóloga se limitó solamente a hacer algunas correcciones de forma y estilo en las traducciones al español sin alterar su contenido.

Animamos a estudiantes de los siete pueblos originarios en la República de Panamá, y a docentes en escuelas, colegios y universidades públicas y privadas en Panamá, a que escriban en sus propios lenguajes y traduzcan al español las etnohistorias y cantos que escuchan en sus familias y comunidades, como parte de su educación informal.

También animamos a lectores de estas etnohistorias en ngäbere, español e inglés, a que dibujen las escenas que más les gustaron, como hicieron en el 2002, estudiantes en un curso de Educación y Sociedad, orientado por la Dra. Joly, en la Facultad de Educación, Universidad Autónoma de Chiriquí.

Artículo 13 de la Declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas, aprobada por la Asamblea General, en su 107ª sesión plenaria el 13 de septiembre de 2007:

- Los pueblos indígenas tienen derecho a revitalizar, utilizar, fomentar y transmitir a las generaciones futuras sus historias, idiomas, tradiciones orales, filosofías, sistemas de escritura y literaturas, y a atribuir nombres a sus comunidades, lugares y personas, así como a mantenerlas.

- Los Estados adoptaran medidas eficaces para asegurar la protección de ese derecho y también para asegurar que los pueblos indígenas puedan entender y hacerse entender en las actuaciones políticas, jurídicas y administrativas, proporcionando para ello, cuando sea necesario, servicios de interpretación u otros medios adecuados.

Los Mironombos y Cronombos cambiaron a los Metobos en forma de árboles y piedras. Así se comenta desde hace buen rato. Los Metobos eran personas grandes y altas, mientras que los Mironombos y Cronombos eran personas pequeñas, de bajas estaturas, con apariencia de mogos y greñones. Por ese motivo estaban considerados como mediocres e incapaces por los Metobos quienes se consideraban de castas sociales avanzadas.

Los Metobos iban a la playa del mar a sacar sal, mientras que los Mironombos y Cronombos iban a las cacerías y pescas a las orillas montañosas del mar. Peces ahumados, carnes de machos de monte, traían los Mironombos y Cronombos; pero, se los quitaban todos en el camino sus verdugos, los Metobos. Con el tiempo, los Mironombos y Cronombos regresaron otra vez a las cacerías y pescas; lo mismo les pasaba en el trayecto de su camino; lo mismo como la vez anterior, víctimas de los Metobos.

Todas las cosas que traían los Mironombos y Cronombos se las quitaban los Metobos por el camino, y después les pegaban, golpeándolos. Luego, los Metobos les decían lo que se les ocurriera en ese momento: “Nosotros hemos hecho esto con ustedes (la humillación); por estos motivos, ¿ustedes que nos van a hacer?” Así ellos les decían a los Mironombos y Cronombos: “Ustedes nos van a cambiar en forma de piedras, árboles; entonces les decimos que viviremos por largos días. ¿Qué nos van a hacer? ¡Digan!” Eso les decían con tono humillante para herirlos más profundo.

Volvían otra vez después de mucho tiempo y les pasaba lo mismo; nunca podían salvarse de los Metobos. Hasta que fue otra vez uno de ellos a la costa del mar. Cuando vino de vuelta de la playa, practicó y midió la fuerza y el poder con los hijos que lo fueron a acompañar.

El padre agarró un virote, lo reventó y lo rajó todo; luego lo tiró al suelo. El hijo primogénito se fue corriendo, lo agarró en la mano, unió los pedazos otra vez y quedó perfectamente como original. El padre lo volvió a hacer pedazos y los tiró al suelo otra vez. El otro hijo se fue corriendo, lo cogió en la mano al igual que el anterior, empató lo pedazos y logró que el virote quedara igual que el anterior como si no hubiera sido roto y rajado.

Al igual que el primero, el segundo hijo hizo lo mismo también. Despedazó el virote, después lo tiró al suelo. El hermano quien le seguía se fue y lo cogió del suelo, después lo unió y quedó magníficamente como el original y como lo hicieron sus hermanos que lo antecedieron.

Completaron este ejercicio cuatro veces. Los cuatro hijos consiguieron tener sus fuerzas y poderes iguales al de su padre. Entonces, ya tenían su carga lista para venir de regreso como siempre, con la pesca y la cacería de animales silvestres, con peces ahumados y carnes ahumadas. Esta vez, como las veces anteriores, se encontraron por el camino con los Metobos quienes les quitaron todas sus cargas, como siempre. Entonces, ellos les dijeron a los Metobos: “No crean; hay peces y animales silvestres más grandes que éstos para ustedes en el mar y en la montaña”. Lo dijeron con tono desafiante y airado, indicando que ya la calma había tenido su fin y que estaban dispuestos a enfrentarse a ellos.

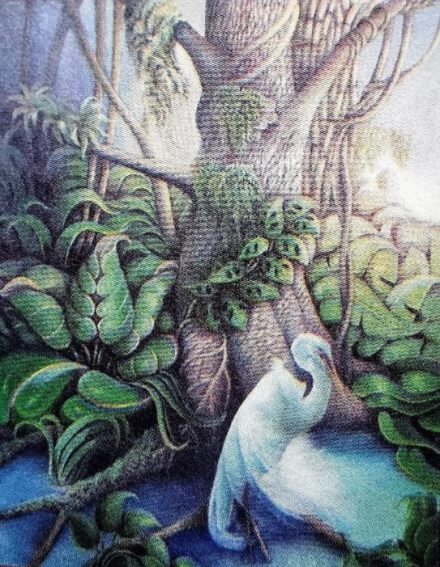

Ilustración de @Madison Heltzel en la portada del libro bilingüe en wayuu y español Resguardo Junna münakat (Las manglares) de Conservación marina sin fronteras. Cita: Thigpen, Robert; Guariyu, Aminta P.; Munar, Alvaro M. M.; (2018) Tü wunu´ulia Junna münakat (Las Manglares. Tesoros del Caribe, Edición de Wayuunaiki) Conservación Marina sin Fronteras, Florence, SC | Illustration by @Madison Heltzel on the cover of the bilingual book in Wayuu and Spanish Resguardo Junna münakat (The mangroves) of Marine Conservation without Borders. Citation: Thigpen, Robert; Guariyu, Aminta P.; Munar, Alvaro M. M .; (2018) Tü wunu´ulia Junna münakat (The Mangroves. Treasures of the Caribbean, Wayuunaiki Edition) Conservacion Marina sin Fronteras, Florence, SC.

Los Metobos entonces les contestaron en tono burlón: “Por esto, entonces, ustedes ¿qué van a hacer? ¿Nos van a convertir en piedras y árboles? Si es así, entonces viviremos para unos días”. Después de decir esto, ellos se fueron para la casa, con las carnes y los peces que lograron quitarles a los Mironombos y Cronombos, sin que éstos les ofrecieran resistencia alguna.

Cuando los Metobos, caminando, llegaron cerca de un cerro llamado Klira, entonces se oscureció el cielo. Todo el cielo quedó cubierto de nubes negras y cayó un gran aguacero. Entonces ellos se pusieron a construir una barraca de hojas de palmas para pasar la lluvia. Cuando cobijaron la barraca con hojas de palma real, no les pasaba agua de lluvia a través de ellas; pero, ocurrió entonces que el agua salía dentro de la casa sobre la superficie de la tierra. Por todas partes salieron riachuelos dentro de la casa, que tumbaron la barraca al suelo.

Entonces, ellos cobijaron las pencas bien tupidas; pero, la lluvia atravesaba todas las pencas y se mojaba todo dentro de la casa. Aunque esta vez el agua no tumbó la casa al suelo, sucedió todo lo contrario, que se mojaba todo. Esto los motivó a tumbar la barraca y comenzar a construir otra vez. Volvieron a cobijar la barraca rala y sucedió lo mismo que la vez anterior: no penetraba la lluvia a través de la misma; pero, se repitió el fenómeno anterior, saliendo riachuelos por todas partes de la casa, que volvieron a tumbar la casa. Ellos volvieron a cobijar la barraca bien tupida; entonces pasó todo lo contrario, la lluvia pasaba toda a través de ella, pero no la tumbó. Una y otra vez intentaron evitar el fenómeno sin poder lograrlo, hasta que anocheció.

Cuando anocheció, entonces no había casa alguna por allí cerca. Sin embargo, de pronto, cerca donde estaban ellos, una lámpara surgió con luz brillante. Uno de ellos dijo a los demás: “Hay casa cerca de aquí y nosotros estamos esclavizándonos aquí innecesariamente bajo la lluvia”. Ellos miraron y vieron una casa grande muy cerca, dentro de la cual veían la luz que reflejaba la claridad, con muchas personas caminando dentro de la casa, para su asombro. Ellos, sin perder tiempo, se dijeron: “Hay casa cerca de aquí y estamos perdiendo tiempo bajo este temporal aquí; vamos para la casa”, y se fueron caminando.

Cuando llegaron al pie de la casa, entonces estaba allí una persona de portero. Miraron para adentro de la casa y vieron muchas personas caminando dentro de la casa. Por otro lado, vieron un enorme asiento de madera labrado, puesto en el centro de la casa. Todos parecían coincidir en ver el mismo panorama. Cuando llegaron a la entrada de la casa, entonces una persona que estaba de portero se avanzó y agarró de la mano al primero y lo llevó y lo sentó en el asiento de madera que estaba adentro de la casa, y así continuó llevando uno por uno hasta acomodarlos a todos sobre el asiento.

Uno por uno, los acomodaron a todos sobre el asiento. Entonces, sólo quedó uno afuera, una persona quien poco valía, quien accidentalmente se encontró también con el grupo sin pertenecer a la clase de los Metobos. Él se hizo de último en la fila y solamente él se quedó afuera. Quiso entrar también en la casa con la comitiva, pero el portero le puso la mamo en el pecho y lo empujó hacia afuera evitando su entrada. “Ese pedazo de yuca sin valor, desperdicio, bótenlo para atrás”. Ese dicho sonó en su oído; él se volteó para irse para atrás. En el instante se produjo un enorme sonido como si se estirara la puerta con fuerza e, inmediatamente, a la vista de él se oscureció todo y con ello desaparecieron de su vista la casa y la lámpara, quedando todo oscuro y en silencio sepulcral. Allí se quedó sin moverse. Cuando vino rayando la aurora, entonces estaba él, para su sorpresa, parado al pie del cerro Klira.

Cuando amaneció bien claro el día, la tal casa no existía. No había rastros de personas, ni indicios que hubiera alguien viviendo cerca de allí.

Aún así, quedaba otro grupo que no llegó al pie del cerro. Al amanecer siguieron su camino con miras a llegar a casa. Éstos eran un grupo considerable que todavía permanecía sano y salvo.

Ellos llegaron a sus respectivas casas. En una de las casas, un muchacho se fue a la quebrada que quedaba cerca de la casa, que era utilizada por ellos para bañarse. De pronto, apareció el muchacho corriendo para la casa y con asombro dijo: “¡Que peces más grandes están ambulando en el charco de la quebrada!” Los viejos que estaban en la casa fueron a ver. Entonces, para su asombro, en el charco que ellos utilizaban para bañarse, se encontraban allí muchos sábalos grandes. Ellos inmediatamente se fueron corriendo y agarraron los sábalos; luego, los prepararon y se los comieron.

Los peces les provocaron diarreas y vómitos, que los llevaron pronto a la muerte, todos los que comieron los peces. Los demás quienes estaban vivos todavía, se fueron a la cacería en la montaña. Ellos se acomodaron en los puntos estratégicos donde pasaban los animales, para tirarlos en sus pasos. Se acomodaron en hilera por el filo de la cordillera montañosa, aguaitando sus presas en sus pasos: venados, saínos, machos de monte y otros. Allí se volvieron todos en forma de árboles y allí están ahora mismo.

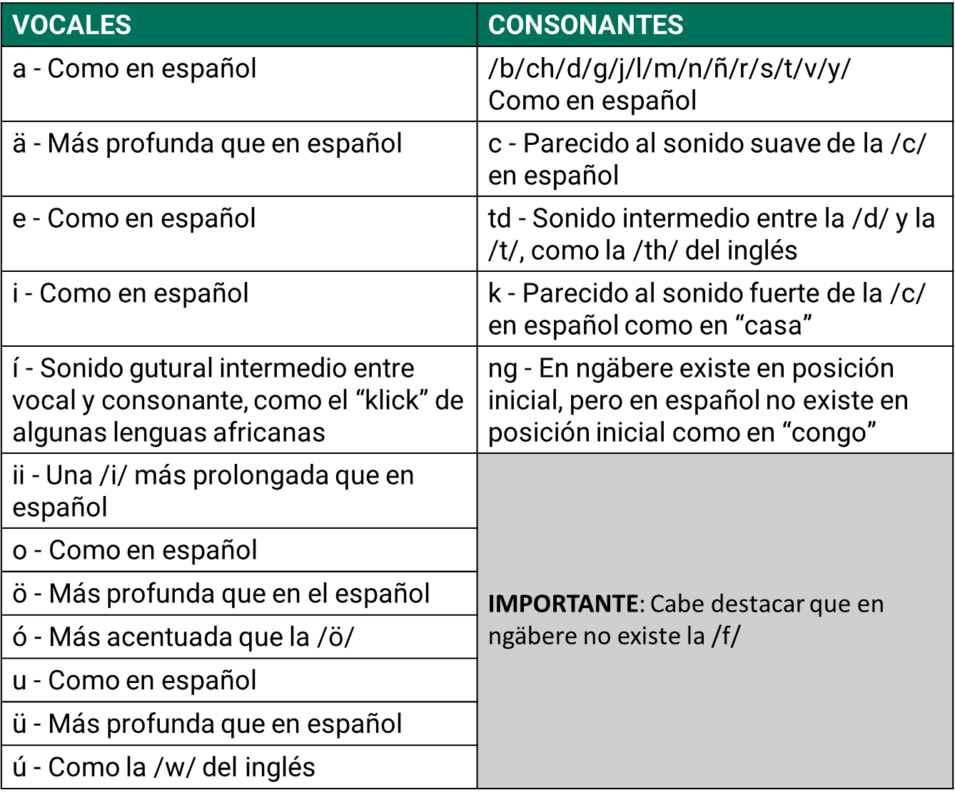

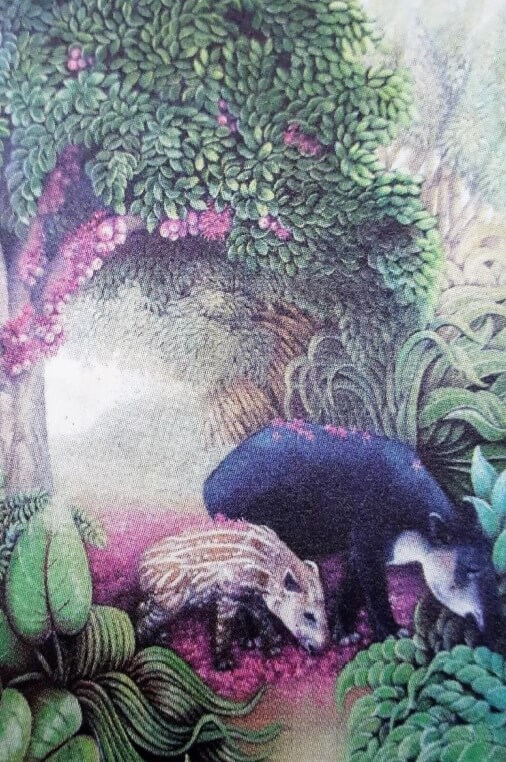

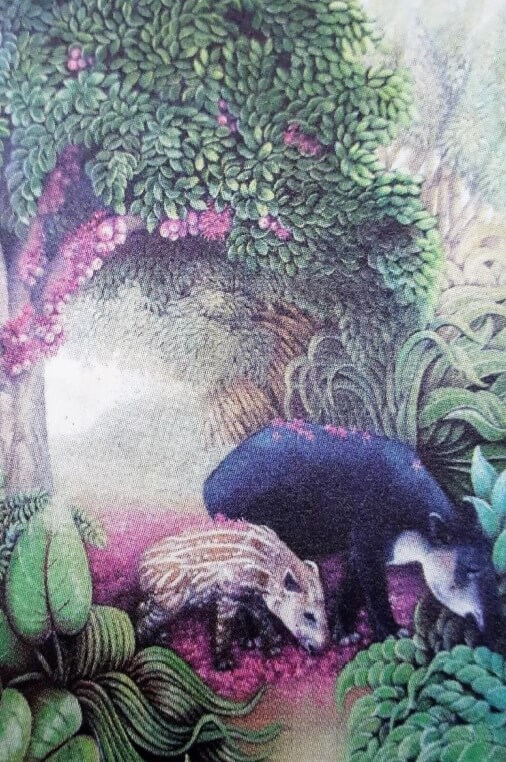

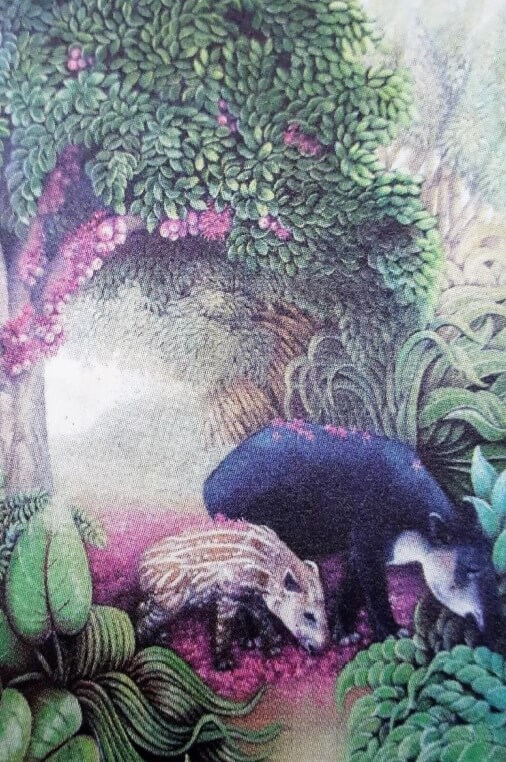

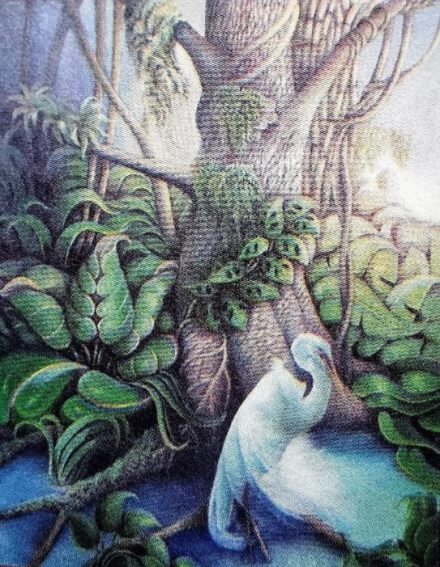

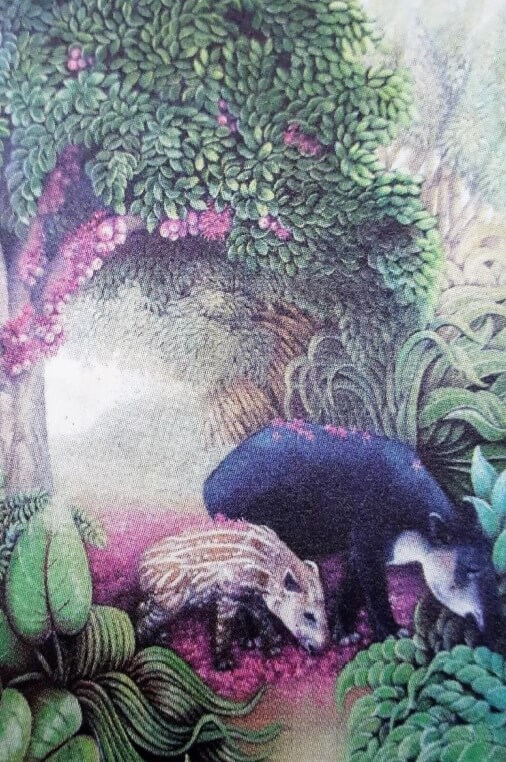

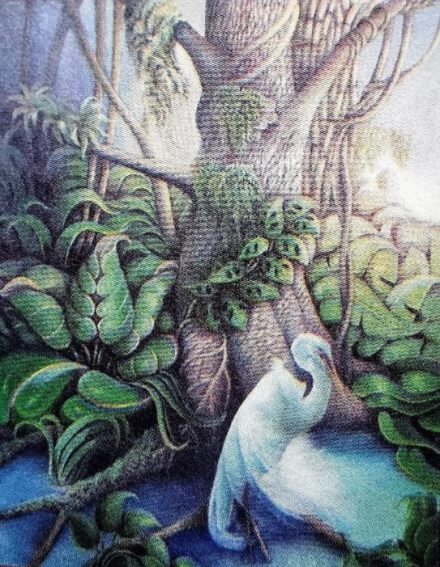

La Senda del Tapir. Óleo en tela de la pintora penonomeña Sonia Solanilla Morales, Museo de Penonomé, Exposición Pictórica “De Mi Terruño, 12 al 20 de diciembre de 2003, Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INAC) en el Centenario de la República | The Path of the Tapir. Oil on canvas by the penonomeña painter Sonia Solanilla Morales, Museum of Penonomé, Pictorial Exhibition “De Mi Terruño, December 12 to 20, 2003, National Institute of Culture (INAC) in the Centennial of the Republic.

Los demás quienes se quedaron en la casa, uno de ellos se fue a bañar y se quedó, no apareció en la casa. Alguien se fue a verlo, entonces no estaba en la quebrada, solamente había una enorme piedra bien acomodada en el charco donde se bañaba. Lo que pasó es que fue convertido en piedra en el charco por los Mironombos y Cronombos.

Venado cola blanca (Odociulus virgininiatus), saino (Tayassu tajacu), cerdo salvaje (Tayassu pecari) Linares, Olga F. “Caza en el jardín en los trópicos americanos” en Ecología humana, vol. 4, No. 4: 331-349, 1976; “Cacería en Huertas” en los Trópicos Americanos. en Evolución en los Trópicos, Panamá: Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute y Editorial Universitaria, 1982: pags.255-268 | Whitetail deer (Odociulus virgininiatus), saino (Tayassu tajacu), wild pig (Tayassu pecari) Linares, Olga F. “Garden Hunting in the American Tropics” in Human Ecology, Vol. 4, No. 4:331-349, 1976; “Cacería en Huertas” en los Trópicos Americanos. en Evolución en los Trópicos, Panamá: Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute y Editorial Universitaria, 1982: pags.255-268.

Así sucedió hace buen rato, comentan los narradores. Los mismos creen que cuando viene el atardecer, entonces todos ellos volverán a ser como personas. Llegan sentencias de los narradores y agregan: “Ellos están vivos, sólo que están cambiados de otra forma, por lo que permanecen estables e inertes en espera del final del día”.

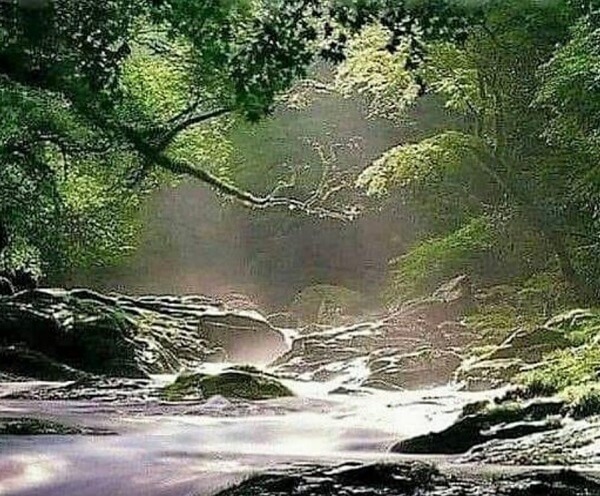

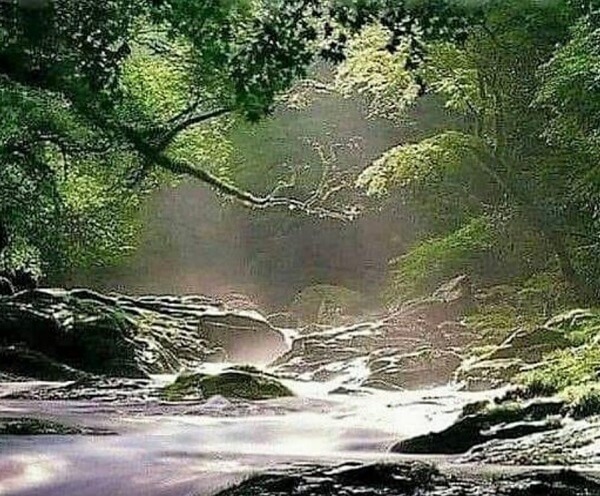

Riveras del Zaratí. Óleo sobre tela de la pintora penonomeña Sonia Solanilla Morales, Museo de Penonomé, Exposición Pictórica “De Mi Terruño, 12 al 20 de diciembre de 2003 Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INAC) en el Centenario de la República | Riveras del Zaratí. Oil on canvas by the penonomeña painter Sonia Solanilla Morales, Museo de Penonomé, Pictorial Exhibition “De Mi Terruño, December 12 to 20, 2003 National Institute of Culture (INAC) in the Centennial of the Republic.

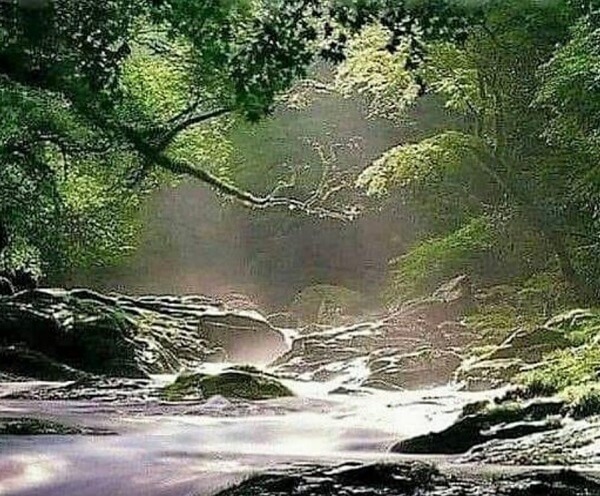

Foto sacada de saludo de Buenos Días en Facebook | Photo taken of good morning greeting on Facebook.

MIRONOMBOS y CRONOMBOS convirtieron a METOBOS en piedras y árboles. A la izquierda foto de piedra tallada en la Reserva Guaimí de Alto Laguna, Sur de Costa Rica. A la derecha árbol en finca privada en Colón. | MIRONOMBOS and CHRONOMBOS turned METOBOS into stones and trees. On the left photo of carved stone in the Guaimí Reserve of Alto Laguna, South of Costa Rica. On the right tree in a private farm in Colón.

Foreword

FOREWORD

To facilitate reading in Ngäbere, we have adapted, with some modifications, the system in the short Ngäbere-Spanish dictionary Kukwe Ngäbere by Melquiades Arosemena and Luciano Javilla, published in 1979 by the Directorate of Historical Heritage of the National Institute of Culture (INAC), now the Ministry of Culture, and the Summer Institute of Linguistics.

It should also be clarified that this story comes from narrators residing in the village of Potrero de Caña, formerly the Tole district of the Chiriquí province, now the Müna district of the Ngäbe Buglé region, from which the Agronomist Roger Séptimo, the compiler and writer is a native. Consequently, the phonology corresponds to the dialectal or regional variation "Guaymí del Interior" (Pacific slope) which differs from the "Guaymí de la Costa" (Caribbean slope of the province of Bocas del Toro and the now district of Kusapin in the Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) in the Guaymí Grammar of Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, published in 1980 by Fe y Alegría. This variant corresponds to what Arosemena and Javilla call "Chiriquí" and which contrasts with the Caribbean variants of Bocas del Toro and the coast of Bocas.

This ethnohistory was published in 1986 in Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere / Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Ethnohistory Guaymí), by the Panamanian Association of Anthropology, with the PN-079 Agreement of the Inter-American Foundation (FIA) managed by Dr. Mac Chapin, Anthropologist, who encouraged us to follow the example he had set by compiling Pab-Igala: Histories of the Kuna Tradition, published in 1970 by the Center for Anthropological Research of the University of Panama, under the direction of Dr. Reina Torres de Araúz.

This book represented the work of the Agricultural Engineer Roger Séptimo, when he was a student in his second year at the Center for Agricultural Teaching and Research in Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, University of Panama (FCAUP), not only writing in Ngäbere the stories that he had heard from his family members in his community, but also his effort to translate them into Spanish as a bilingual person that he is, like other indigenous people in Panama, who are striving to receive a formal education.

The ethnohistories were compiled, recorded on cassettes and written by the Agronomist Roger Séptimo in 1983 and 1984.

As Professor-Researcher of Anthropology and Rural Sociology at the CEIACHI of the FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Anthropologist, Ph.D., encouraged Roger, as one of her students, to write the stories, convince him and show him that she would not exploit or abuse his work, but that he would get credit. Consequently, the anthropologist limited herself only to making some corrections of form and style in the Spanish translations without altering their content.

We encourage students from the seven indigenous peoples in the Republic of Panama, and teachers in public and private schools, colleges and universities in Panama, to write in their own languages and translate the ethnohistories and songs they hear in their families and communities into Spanish, as part of their informal education.

We also encourage readers of these ethnohistories in Ngäbere, Spanish and English, to draw the scenes that they liked the most, as they did in 2002, students in an Education and Society course, directed by Dr. Joly, at the Faculty of Education, Autonomous University of Chiriquí.

Article 13 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, approved by the General Assembly, in its 107th plenary session on September 13, 2007:

- Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, promote and pass on to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to name and maintain their communities, places and people.

- The States shall adopt effective measures to ensure the protection of this right and also to ensure that indigenous peoples can understand and make themselves understood in political, legal and administrative actions, providing for this, when necessary, interpretation services or other appropriate means.

The Mironombos and Cronombos changed the Metobos in the forms of trees and stones. That is what is commented since a long time ago. The Metobos were big and tall persons, while the Mironombos and Cronombos were small persons, of a low height, and looked silly and with entangled or matted hair. For this reason, they were considered mediocre and incapable by the Metobos who considered themselves of a more advanced social class.

The Metobos would go to the seashore to extract salt, while the Mironombos and Cronombos would hunt and fish in the rainforests near the seashore. The Mironombos and Cronombos would bring smoked fish and meats of wild pigs (Tayassu pecari), but the rappers would take it away from them on the trail. After a while, the Mironombos and Cronombos would hunt and fish again; the same would occur again on their way home; they would become victims of the Metobos, as before.

All the things that the Mironombos and Cronombos would bring, the Metobos would take them on the trail home, and would then hit them. The Metobos would say whatever they wanted at that moment to the Mironombos and Cronombos: “We have done this to you (the humiliation); for this reason, ¿what will you do to us? You are going to change us in the forms of stones and trees; then we tell you that we will live for long days. ¿What are you going to do? ¡Say it!” The Metobos would say these things in a humiliating tone to injure them deeply in their inner self.

The Mironombos and Cronombos would go again after a long time, and the same would occur; they could never be safe from the Metobos. Until one time, one of the Mironombos and Cronombos went to the seashore again. When he reached the seashore, he practiced and measured his strength and power with his sons who accompanied him.

The father got a stick, broke it, and split the wood; then he threw it to the ground. The firstborn son went running, got it in his hands, joined the pieces again and it became perfect as originally. The father again broke it into pieces and again threw it to the ground. The other son came running, got it in his hands as his brother before him did, joined the pieces and was able to get the stick as originally it was before, as if never had been broken and split.

As the firstborn, the second son did the same again. He broke the stick and then threw it to the ground. The other brother who followed him picked it from the ground, then joined the pieces, and it became magnificently well as originally, as was done by his brothers before.

The exercise was completed four times. The four sons were able to have the strength and power as their father. Then they had the cargo ready to return home as usual, the fish and wild animals, as smoked fish and smoked meats. This time, as in previous times, they met the Metobos on the trail, who took their cargo, as always. Then they told the Metobos: “You won´t believe it, there are fishes and wild animals bigger than these for you in the sea and in the rainforest”. They said it in a defiant and arrogant tone, indicating that their calm had come to an end and that they were ready to confront the Metobos.

Ilustración de @Madison Heltzel en la portada del libro bilingüe en wayuu y español Resguardo Junna münakat (Las manglares) de Conservación marina sin fronteras. Cita: Thigpen, Robert; Guariyu, Aminta P.; Munar, Alvaro M. M.; (2018) Tü wunu´ulia Junna münakat (Las Manglares. Tesoros del Caribe, Edición de Wayuunaiki) Conservación Marina sin Fronteras, Florence, SC | Illustration by @Madison Heltzel on the cover of the bilingual book in Wayuu and Spanish Resguardo Junna münakat (The mangroves) of Marine Conservation without Borders. Citation: Thigpen, Robert; Guariyu, Aminta P.; Munar, Alvaro M. M .; (2018) Tü wunu´ulia Junna münakat (The Mangroves. Treasures of the Caribbean, Wayuunaiki Edition) Conservacion Marina sin Fronteras, Florence, SC.

The Metobos then answered in a scoffing tone: “For this, then, what will you do? You are going to convert us into stones and trees; if it is that way, then we will live for some days.” After saying this, the Metobos went home with the fish and meats that they had taken from the Mironombos and Cronombos, without the latter offering any resistance.

When the Metobos, walking, got near a hill called Klira, then the sky got dark. All the sky got covered with black clouds and a great rain fell. Then they began to construct a shack with palm leaves to cover themselves from the rain. When they covered the shack with the leaves of the royal palm, the rain would not pass through the leaves, but then the water would come out inside the house from the surface of the ground. Everywhere sprang streams of water inside the house, so that the shack fell to the ground.

Then they covered the shack with palm leaves very closely woven, but the rain would go through the palm leaves and the shack got all wet inside. Although this time the water did not throw the shack down, the contrary occurred that everything got wet. This motivated them to throw the shack down and build another one. They covered the shack thinly with palm leaves and the same thing occurred as before: the rain would not pass through the palm leaves, but the same phenomenon occurred that streams of water appeared everywhere inside the shack that fell again. They covered the shack densely with palm leaves; then occurred the reverse, the rain would pass through but did not throw the shack down. Over and over again, they tried to avoid this phenomenon, but could not achieve it, until it became night.

When nighttime came, then there was no house near there. However, suddenly, near to where they were, a bright light from a lamp could be seen. One of them said to the others: “There is a house near here and we are being enslaved here unnecessarily by this rain.” They looked and saw a big house very near, inside of which they could see the light clearly reflecting, with many people walking inside the house, to their amazement. They, without losing time, said: “There is a house near here and we are losing time under this rainstorm; let´s go to the house”; and they went walking.

When they got at the foot of the house, then there was a person as porter. They looked inside the house and saw many persons walking inside the house. On another place they saw an enormous seat of polished wood inside the house. All of them seemed to coincide in seeing the same panorama. When they got to the entrance of the house, then the person who was there as porter, advanced and got the hand of the first one and seated him on the wooden seat inside the house and continued taking one by one until he accommodated all on the seat.

One by one all were accommodated on the seat. Then, only one remained outside, a person of little value, who accidentally met the group without belonging to the class of Metobos. He was the last one on the line and only he remained outside. He also wanted to go inside the house with the group, but the porter put his hand on the chest of that person and pushed him out avoiding his entrance. “That piece of manioc has no value, garbage, throw him back.” At that instant, there was an enormous sound as if the door had been forcefully stretched and immediately in his sight everything darkened and with that the house and the lamp disappeared from his sight, being all in the darkness and in sepulchral silence. There he remained without moving. When dawn came, then he was, to his surprise, standing at the foot of the Klira hill.

When daybreak very clearly appeared, such a house did not exist. There were no signs of persons, nor marks that there was someone living near there.

Even so, there was another group that did not get to the foothill. With the daybreak, they continued their way home. This was a considerable group that still remained safe and sound.

They arrived at their respective houses. In one of the houses, a boy went to the stream that was near the house, which was used by them for bathing. Suddenly, the boy appeared running toward the house and with astonishment said: “What big fishes are swimming in the pool of the stream!” The old men who were in the house went to see. Then, to their surprise, in the pool that they used for bathing, were many big shads (Brycon). They immediately went running and caught the shads, then cooked them and ate them.

The fish provoked them diarrhea and vomiting, that soon took them to their death, all who ate the fish. The rest who was alive went to the rainforest to hunt. They accommodated themselves at strategic points where the animals pass, to kill them as the animals passed.

La Senda del Tapir. Óleo en tela de la pintora penonomeña Sonia Solanilla Morales, Museo de Penonomé, Exposición Pictórica “De Mi Terruño, 12 al 20 de diciembre de 2003, Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INAC) en el Centenario de la República | The Path of the Tapir. Oil on canvas by the penonomeña painter Sonia Solanilla Morales, Museum of Penonomé, Pictorial Exhibition “De Mi Terruño, December 12 to 20, 2003, National Institute of Culture (INAC) in the Centennial of the Republic.

They accommodated themselves at the top of the mountain ridge, waiting for their prey to pass: deer, sainos (Tayassu tajacu), wild pigs (Tayassu pecari), and others. There those Metobos became trees that are still there.

Venado cola blanca (Odociulus virgininiatus), saino (Tayassu tajacu), cerdo salvaje (Tayassu pecari) Linares, Olga F. “Caza en el jardín en los trópicos americanos” en Ecología humana, vol. 4, No. 4: 331-349, 1976; “Cacería en Huertas” en los Trópicos Americanos. en Evolución en los Trópicos, Panamá: Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute y Editorial Universitaria, 1982: pags.255-268 | Whitetail deer (Odociulus virgininiatus), saino (Tayassu tajacu), wild pig (Tayassu pecari) Linares, Olga F. “Garden Hunting in the American Tropics” in Human Ecology, Vol. 4, No. 4:331-349, 1976; “Cacería en Huertas” en los Trópicos Americanos. en Evolución en los Trópicos, Panamá: Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute y Editorial Universitaria, 1982: pags.255-268.

The rest who stayed home, one of them went to bathe himself and did not return home. Someone went to find him, and did not see him in the stream, where there was only an enormous stone well accommodated in the bathing pool. What happened was that the Mironombos and Cronombos converted him into that stone in the pool.

That is what happened a long time ago, commented the storytellers. They believe that when the sunset comes, then the Metobos will again become human persons. The sentencing storytellers added: “They are alive, only that they have been transformed, and so they remain stable and inert waiting for the final day.”

Riveras del Zaratí. Óleo sobre tela de la pintora penonomeña Sonia Solanilla Morales, Museo de Penonomé, Exposición Pictórica “De Mi Terruño, 12 al 20 de diciembre de 2003 Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INAC) en el Centenario de la República | Riveras del Zaratí. Oil on canvas by the penonomeña painter Sonia Solanilla Morales, Museo de Penonomé, Pictorial Exhibition “De Mi Terruño, December 12 to 20, 2003 National Institute of Culture (INAC) in the Centennial of the Republic.

Foto sacada de saludo de Buenos Días en Facebook | Photo taken of good morning greeting on Facebook.

MIRONOMBOS y CRONOMBOS convirtieron a METOBOS en piedras y árboles. A la izquierda foto de piedra tallada en la Reserva Guaimí de Alto Laguna, Sur de Costa Rica. A la derecha árbol en finca privada en Colón. | MIRONOMBOS and CHRONOMBOS turned METOBOS into stones and trees. On the left photo of carved stone in the Guaimí Reserve of Alto Laguna, South of Costa Rica. On the right tree in a private farm in Colón.

Mironombo, Cronombo kägue Metobo kuiti, järe kue.

Metobo abogo ni krígri, nganga kuin amlen Mironombo, Cronombo abogo ni kiaguia, doguä jubejube abogo bata nibi toen nguarabe ribanga bogon-bogon Metobo ye. Metobo abogo nomlen nebe mren dengä möta amlen Mironombo, Cronombo abogo nomlen nebetre mundiare mrenbata: gua nöta, mölö nöta jänomlen kitetre kue dianca nomlen jogrä kon jitde ribanga metobogüe. Kirara rigata buguta krere noentdatre bata jite bugutadre Metobogüe. Jondron diangatre jogrä kon kuetre biti meta kue, biti ñägätre kue ie: titda kugüe noenen mabata, nebata magüe ti noendi nietre kue ie, magüe ti kuitei järe, krire ya, ne amlen tigüe nünein köbäti, magüe guiere noendi nierabe nitre kuetre ie. Ne kridiare, biti jalinta büguta iti möta, kita amlen ja gari kue ngobobe. Drörä kari kue nguilingä jogrä kue biti kiti temen kue. Ngöbo mubiai nigui vetegä kägüe dilin kitigäta jabata kue nibita tätde ie. Abogo kägüe nguligäta kititda temen kue ngobo iti, nigui vetegä kaguë dilin mada kägüe kitigäta jabata nibita tätde arato ie.

Ne abogo kägue nünin krere arato. Drörä nguilingäta kue biti kititda temen kue eteba nigui kägüe dilin kisete kitigäta kue jabata nibita tätde ie arato. Nibi tätde bäbogä ie di nibi ja näre jogrä nibogä. Ne abogo mundianri möta kue: gua nöta, ngrí nöta jägui kue. Metobo ngötätda ven büguta kägüe dilingäta jogrä kon. Amlen ninin kue Metobo ye kä mriäne tägua, kä mriäne tä magrä ñöte gua ye, ninin kue ie. Metobo abogo kägüe ninin mada ie, nebata abogo magüe ti noendi, magüe ti juein ñö-tdeya, magüe ti kuitei järe, krire ne amlen tigüe nüadi köböti ninin kue ie. Biti kitadre.

Ilustración de @Madison Heltzel en la portada del libro bilingüe en wayuu y español Resguardo Junna münakat (Las manglares) de Conservación marina sin fronteras. Cita: Thigpen, Robert; Guariyu, Aminta P.; Munar, Alvaro M. M.; (2018) Tü wunu´ulia Junna münakat (Las Manglares. Tesoros del Caribe, Edición de Wayuunaiki) Conservación Marina sin Fronteras, Florence, SC | Illustration by @Madison Heltzel on the cover of the bilingual book in Wayuu and Spanish Resguardo Junna münakat (The mangroves) of Marine Conservation without Borders. Citation: Thigpen, Robert; Guariyu, Aminta P.; Munar, Alvaro M. M .; (2018) Tü wunu´ulia Junna münakat (The Mangroves. Treasures of the Caribbean, Wayuunaiki Edition) Conservacion Marina sin Fronteras, Florence, SC.

Ñü jingrabre gütio gä klirabata amlen kä nöte, kä nibi ico jogrä, ñügüi temen. Amlen nibira ju bigue. Ju biga oglare kue amlen nin ñüraba vetegä teta, amlen ñó jata vetegä güigüin, jata nogregä jogrä güita temen kägüe ju kuitaga temen.

Ven ju biga vitibe kuetre amlen ñü raba vetegä jogrä teta abogo kägüe nin kuitaga temen. Bata diganteda kue, bigata oglare kue amlen ñü raba vetegä ñakara teta amlen jatatda vetegäta jogrä güita temen, kägüe ju kitagata temen, ne ven bigata vitibe kue amlen ñü raba vetegä ñagare güita amlen raba vetegë jogrä juteta abogo nin rigüitaga temen aibe jänglun, abogo ve bata kä güi de temen ietre.

La Senda del Tapir. Óleo en tela de la pintora penonomeña Sonia Solanilla Morales, Museo de Penonomé, Exposición Pictórica “De Mi Terruño, 12 al 20 de diciembre de 2003, Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INAC) en el Centenario de la República | The Path of the Tapir. Oil on canvas by the penonomeña painter Sonia Solanilla Morales, Museum of Penonomé, Pictorial Exhibition “De Mi Terruño, December 12 to 20, 2003, National Institute of Culture (INAC) in the Centennial of the Republic.

Kä guí igo amlen ju ñagare jaken amatibe vatibe jaken se krere ñötra oguä nguitigä ngüen, amlen iti kägüe ninin ietre ju ye tärä jaken nete ni abogo käta jamigue enne nete ñaña ninin kue. Nigra nire kue amlen ju krií se krere te ñötra nibi toen ngüen, ni diaguegä kuati güita nibi toentre ie.

Amlen ninintre kue ju ye tärä kälimen ni abogo kä ta jamigue enne nete, mun anlin guä ninentre kue nigui. Ki matde guägrä amlen ni tdonlin iti jugüete se krere, nigra-nri guä kue amlen ni nibi toen diguegä kuäti güita ietre, amlen kri-krií mialin kä te röare güi nibi toen ie.

Ki guägrä amlen ni tdonlin jugüete se krere kä nigui kain itire küdebiti ügate nigui kribiti kä te röare se krere.

Ugate nigué itire, itire jogrä güi kribiti. Amlen nebe itibe, ni döguai, nguarabe se krere abogo ve nebe mrä, bi niguen arato guä amlen kise miribata kitigäta ja jiöbiti küguen. Ö oto ngarabe ye mialingäta ja jiöbiti ninin, nigüitdetda ja jiöbiti kä ngö nibigä klugube kä nguidite be oguäte. Kontdi nebe, kä gui nögaingä degä amlen tä nünalingo güitio ne ngüre bata, kä guí ngüen biti amlen ju ñácara, kä nguarabe. Nebe abogo degä niguita ta, nebe kabre jabata niguitatre.

Venado cola blanca (Odociulus virgininiatus), saino (Tayassu tajacu), cerdo salvaje (Tayassu pecari) Linares, Olga F. “Caza en el jardín en los trópicos americanos” en Ecología humana, vol. 4, No. 4: 331-349, 1976; “Cacería en Huertas” en los Trópicos Americanos. en Evolución en los Trópicos, Panamá: Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute y Editorial Universitaria, 1982: pags.255-268 | Whitetail deer (Odociulus virgininiatus), saino (Tayassu tajacu), wild pig (Tayassu pecari) Linares, Olga F. “Garden Hunting in the American Tropics” in Human Ecology, Vol. 4, No. 4:331-349, 1976; “Cacería en Huertas” en los Trópicos Americanos. en Evolución en los Trópicos, Panamá: Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute y Editorial Universitaria, 1982: pags.255-268.

Nibita griete amlen ngäbägre güi se krere nigui möta ñöbata, kita vetegä guägrä kägüe ninin ¡Aite! gua kiabe tä kuite ñötö möta yera ninin kue, niguitre mie ñöräre amlen ñöoguä jübagrä möta se krere te driga krigribe tonlin kuite. Ni guitre vetegä gua karitre kue biti kuititre kue gua nigüi griere, yare bata aibe kägüe kitigä jogrä. Nebe röäre abogo nigui mundiare, nibi ja ügalinte girere jüdreta temen ngrí kraire jite kontdi nigüi krire jogrä, ne abogo tä kälimen.

Nebe güi abogo nigui juben möta, ñákara, kä nibi ulire kue. Mia nigui ñäräre amlen ñákara möta, jä be krií kuekuebe ñöoguäte, ne amlen kuiti järe möta Mironombo, Cronombogüe. Kugüe nögalingä krörö meguera kädrie ngäbe güe temen.

Kä de amlen rügueita nire jogrä nienri dera ngäbe güe. Tä nire akua kuitalin bä genen abogo bata tä kueguebe nie.

Riveras del Zaratí. Óleo sobre tela de la pintora penonomeña Sonia Solanilla Morales, Museo de Penonomé, Exposición Pictórica “De Mi Terruño, 12 al 20 de diciembre de 2003 Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INAC) en el Centenario de la República | Riveras del Zaratí. Oil on canvas by the penonomeña painter Sonia Solanilla Morales, Museo de Penonomé, Pictorial Exhibition “De Mi Terruño, December 12 to 20, 2003 National Institute of Culture (INAC) in the Centennial of the Republic.

Foto sacada de saludo de Buenos Días en Facebook | Photo taken of good morning greeting on Facebook.