Prólogo

PRÓLOGO

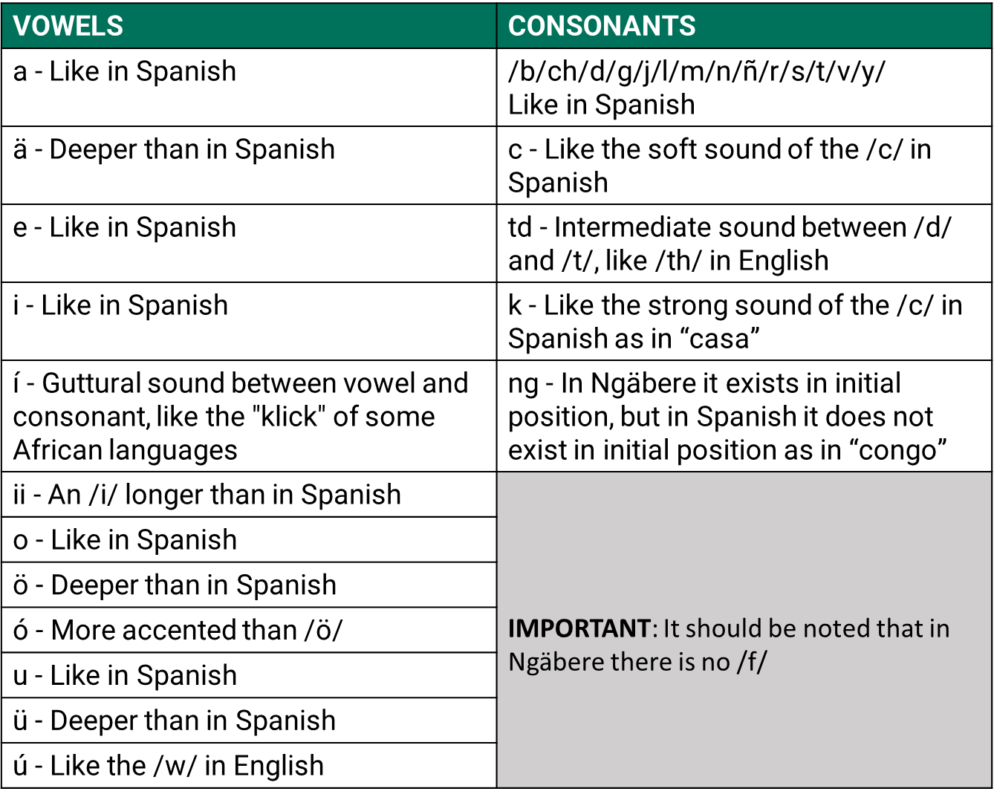

Para facilitar la lectura en ngäbere, hemos adaptado, con algunas modificaciones, el sistema en el breve diccionario ngäbere-español Kukwe Ngäbere de Melquiades Arosemena y Luciano Javilla, publicado en 1979 por la Dirección del Patrimonio Histórico del Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INAC), ahora Ministerio de Cultura, y el Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

También conviene aclarar que esta historia proviene de narradores residentes en el corregimiento de Potrero de Caña, antes distrito de Tole de la provincia de Chiriquí, ahora distrito de Müna de la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé, de donde es oriundo el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, el recopilador-escritor. Por consiguiente, la fonología corresponde a la variación dialectal o regional “Guaymí del Interior” (vertiente del Pacífico) y que difiere del “Guaymí de la Costa” (vertiente caribeña de la provincia de Bocas del Toro y del ahora distrito de Kusapin en la Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) en la Gramática Guaymí de Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, publicada en 1980 por Fe y Alegría. Esta variante corresponde a la que Arosemena y Javilla denominan “Chiriquí” y que contrasta con las variantes caribeñas de Bocas del Toro y costa de Bocas.

Esta etnohistoria fue publicada en 1986 en Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere/Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Etnohistoria Guaymí), por la Asociación Panameña de Antropología, con el Convenio PN-079 de la Fundación Inter-Americana (FIA) gestionada por el Dr. Mac Chapin, Antropólogo, quien nos animó a que siguiéramos el ejemplo que él había sentado al recopilar el Pab-Igala: Historias de la Tradición Kuna, publicadas en 1970 por el Centro de Investigaciones Antropológicas de la Universidad de Panamá, bajo la dirección de la Dra. Reina Torres de Araúz.

Este libro representó la labor del Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo, cuando era estudiante en su segundo año en el Centro de Enseñanza e Investigación Agropecuaria de Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad de Panamá (FCAUP), no solo de escribir en ngäbere las narraciones que había oído relatar a sus familiares en su comunidad, sino también su esfuerzo de traducirlas al español como persona bilingüe que es, al igual que otros indígenas en Panamá quienes se esfuerzan por recibir una educación formal.

Las etnohistorias fueron recopiladas, grabadas en casetes y escritas por el Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo en 1983 y 1984.

Como Profesora-Investigadora de Antropología y Sociología Rural en el CEIACHI de la FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Antropóloga, Ph.D., animó a Roger, como uno de sus estudiantes, a escribir las historias, convencerlo y demostrarle que no explotaría ni abusaría de su trabajo, sino que se le reconocería su mérito. Por consiguiente, la antropóloga se limitó solamente a hacer algunas correcciones de forma y estilo en las traducciones al español sin alterar su contenido.

Animamos a estudiantes de los siete pueblos originarios en la República de Panamá, y a docentes en escuelas, colegios y universidades públicas y privadas en Panamá, a que escriban en sus propios lenguajes y traduzcan al español las etnohistorias y cantos que escuchan en sus familias y comunidades, como parte de su educación informal.

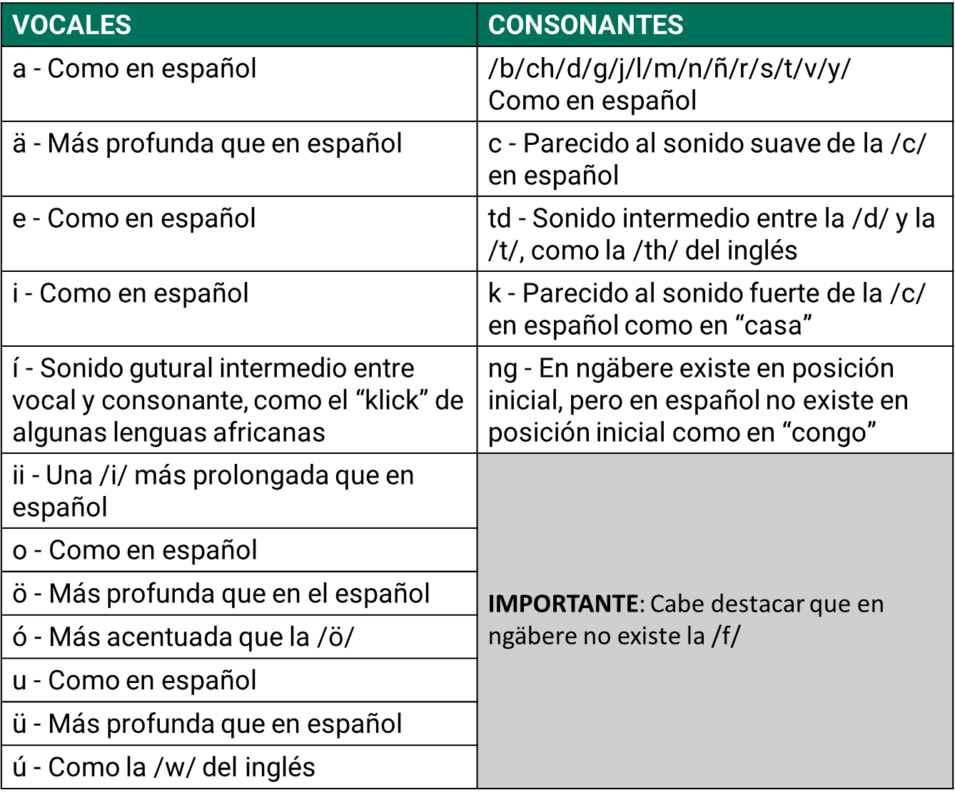

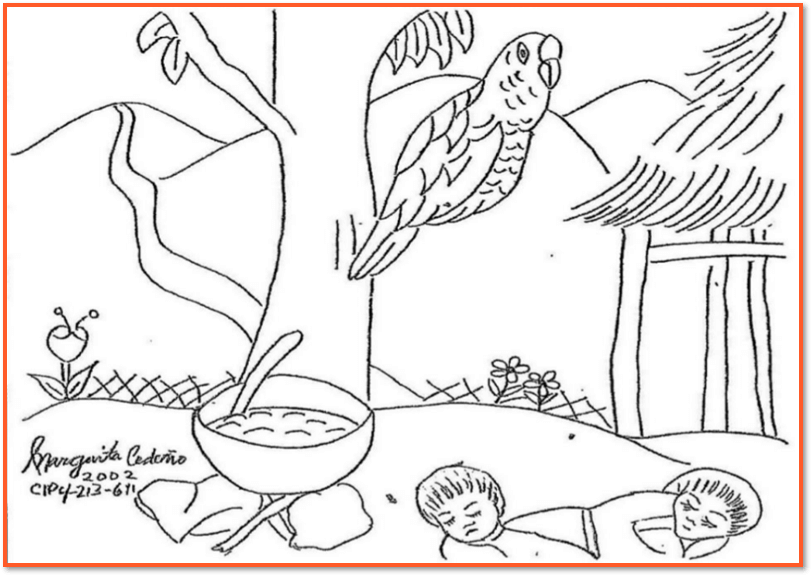

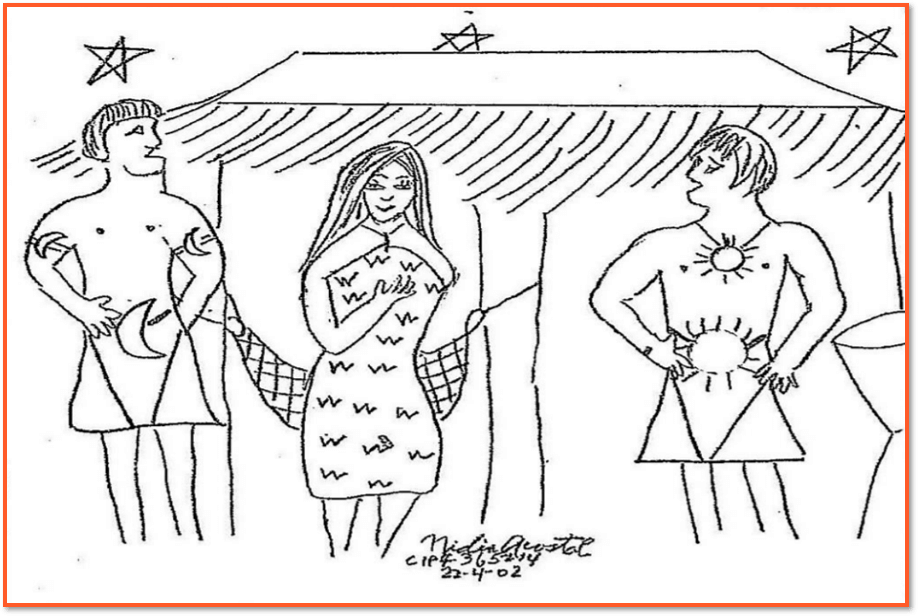

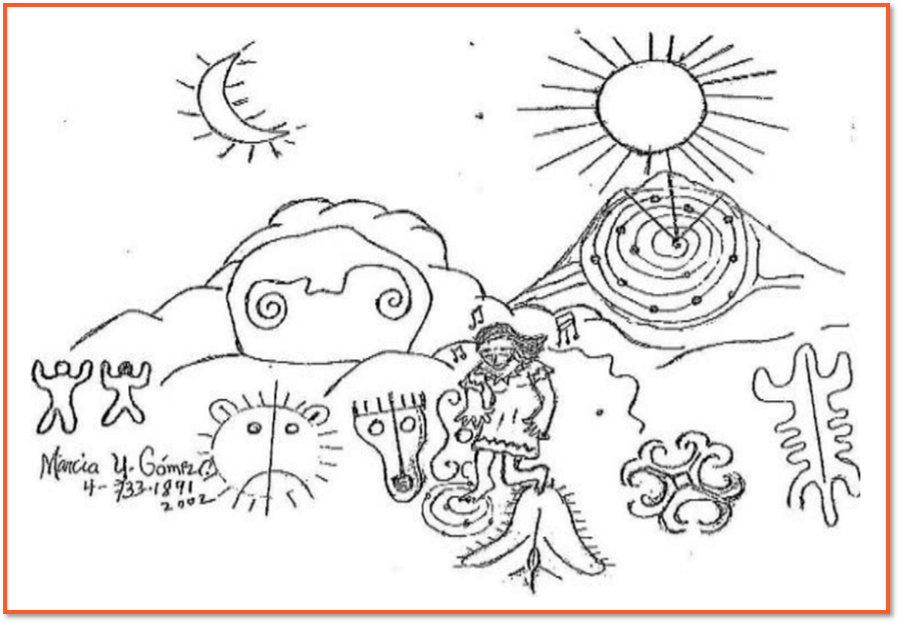

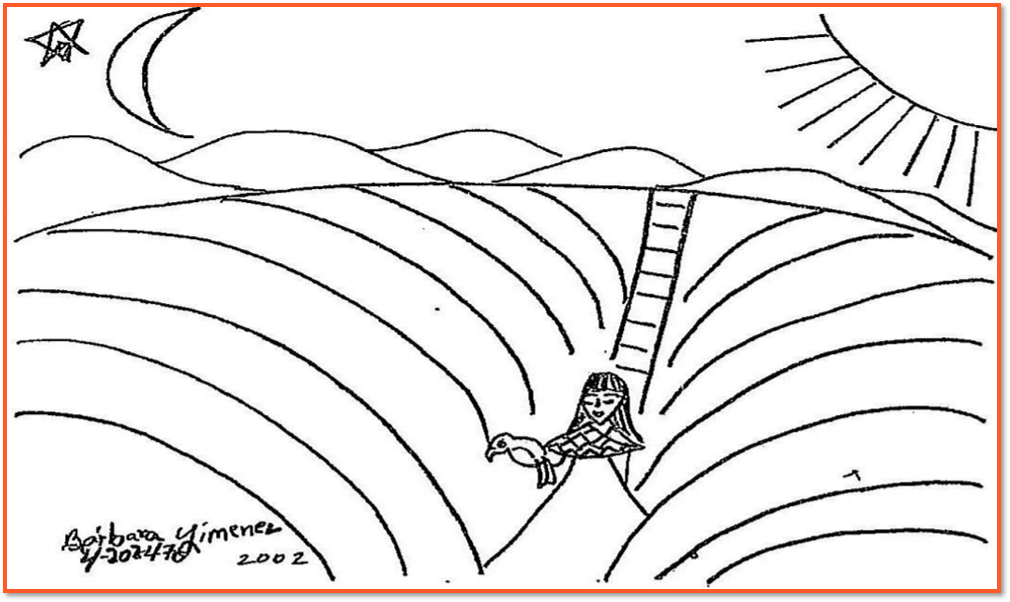

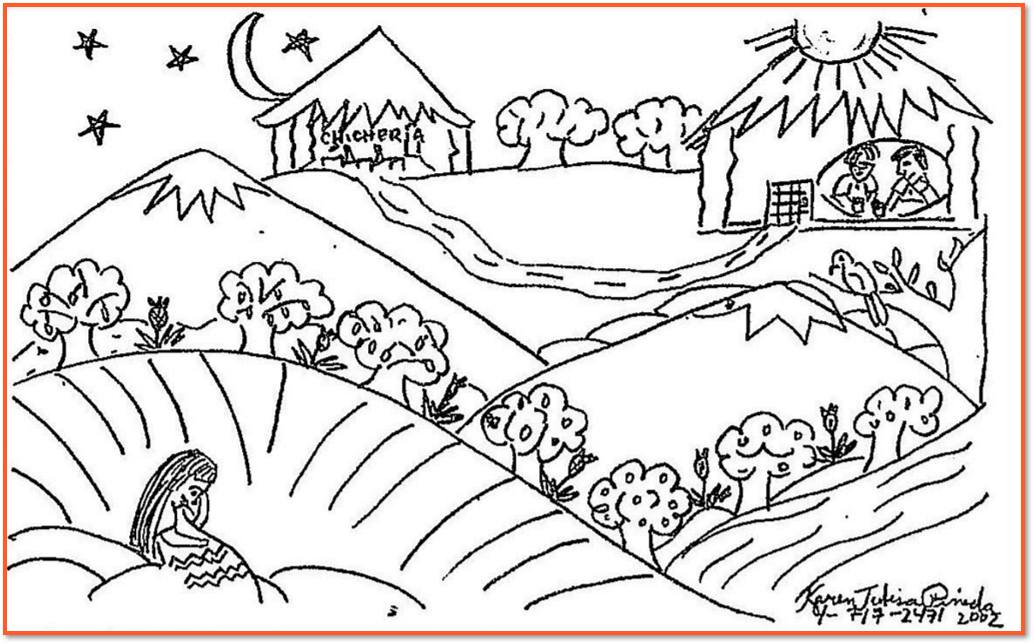

También animamos a lectores de estas etnohistorias en ngäbere, español e inglés, a que dibujen las escenas que más les gustaron, como hicieron en el 2002, estudiantes en un curso de Educación y Sociedad, orientado por la Dra. Joly, en la Facultad de Educación, Universidad Autónoma de Chiriquí.

Artículo 13 de la Declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas, aprobada por la Asamblea General, en su 107ª sesión plenaria el 13 de septiembre de 2007:

- Los pueblos indígenas tienen derecho a revitalizar, utilizar, fomentar y transmitir a las generaciones futuras sus historias, idiomas, tradiciones orales, filosofías, sistemas de escritura y literaturas, y a atribuir nombres a sus comunidades, lugares y personas, así como a mantenerlas.

- Los Estados adoptaran medidas eficaces para asegurar la protección de ese derecho y también para asegurar que los pueblos indígenas puedan entender y hacerse entender en las actuaciones políticas, jurídicas y administrativas, proporcionando para ello, cuando sea necesario, servicios de interpretación u otros medios adecuados.

EL SOL Y LA LUNA

Se dice que había una señora llamada Evia, quien vivía solamente con dos hijos muy pequeños, quienes nadie sabía quién había sido su padre. Pero lo cierto era que había dos niños viviendo con la señora. Los dos niños vivían en condiciones insalubres, todos mugrientos: su único alojamiento era el fogón de la casa alrededor del cual siempre estaban sentados o acostados en la ceniza. Muy pocas veces salían hacia otra parte.

Su madre siempre le gustaba estar de fiesta en fiesta, porque ella era una notable cantora. En una de estas fiestas se encontró con dos hombres. Uno estaba vestido de oro y con bastón de oro en la mano, mientras que el otro tenía vestido de color plata (blanco) y con bastón de plata. La señora vio a los dos tan atractivos y le llamó tanto la atención que ella se dedicó a adornarse con todo tipo de prendas y vestirse lo mejor posible para llamar la atención de uno de los dos hombres.

Ella se dedicó a cantar al frente de los dos y les pisaba los pies para demostrar que a ella le gustaban esos hombres. No estando conforme ella con esa demostración, decidió hacer gestos y mímicas delante de ellos para llamarles más la atención. Pero ninguna de esas demostraciones parecía tener importancia para esos hombres. Lo único que hacían ellos era mover los pies y mudarse de lugar sin el mínimo interés puesto en ella.

Pero había alguien que sí conocía la procedencia de esos hombres. En verdad, ellos eran los hijos de la señora. Esa persona le advirtió a la señora que no estuviera haciendo tales espectáculos desagradables ya que esos hombres eran sus dos hijos.

Ella respondió diciendo que no eran sus hijos, ya que los pobres niños se habían quedado mugrientos, acostados en la ceniza del fogón de la casa cuando ella se había ido para la fiesta y que jamás se podían comparar con las figuras de dos hombres tan notables.

Los dos hombres en ningún momento le prestaron atención a ella y siguieron participando en la fiesta sin novedad. Ella insistió en seguirlos a ellos hasta culminar la fiesta. No pudiendo lograr su intención, regresó a su casa. Para su sorpresa, allí se encontraban los dos niños sentados alrededor del fogón. Esto le infundió más confianza a ella en creer que esos dos hombres que ella había visto en la fiesta no eran sus hijos. Esto significaba que ella no conocía a sus hijos, ni el poder que tenían sus hijos para aparecer como los hombres con los que se encontró.

Luego le llegó la oportunidad de ir a otra fiesta y se dio la coincidencia que se encontró con los mismos hombres. Sin dar lugar a desperdiciar tiempo, ella reanudó las mismas demostraciones para llamar nuevamente la atención de sus codiciados hombres. Ella esperaba que al menos uno de los dos podía interesarse por ella. Pero, como la primera vez, no consiguió nada de esos dos hombres.

Como la vez anterior, había una persona que le llamó la atención, que hiciera el favor de no cometer tan semejante acto inmoral y penoso. Pero ya ella no le creía a nadie, ya que la primera vez cuando llegó a la casa allí estaban sus dos niños en la casa junto al fogón.

A pesar de todo su empeño, tampoco esta vez logró interesar a los dos hombres en su persona. Ellos siempre trataban de evadir su presencia por las cosas que ella les hacía.

Terminada la chichería, ella volvió para la casa, encontrando a los dos niños al pie del fogón tal como los encontró en la vez anterior. Esto le causaba a ella confusión y no podía creer que esos eran sus hijos.

Volvió ella a asistir a otra chichería y se repitió por tercera vez el mismo fenómeno inexplicable para su suerte. La cosa que más le preocupaba a ella era que, aunque esos hombres le gustaban, siempre había alguien que le mortificaba a su conciencia diciéndole que eran sus hijos.

Esta vez, más confusa que nunca, volvió a su casa y, para el colmo de su suerte, siempre estaban allí los dos niños en la casa.

Cuando le tocó a ella ir a otra chichería, por cuarta vez se encontró con esos dos hombres. Para salir de una vez por todas de la duda, ella se fue para la chichería, pero en medio del camino se escondió a un lado del camino a esperar si eran esos hombres sus hijos. Entonces iba a ver si ellos salían detrás de ella y de esta forma lograba verlos pasar. Para su sorpresa, vio pasar esos mismos hombres detrás de ella e ir para la chichería. Motivada ella por esa sorpresa, no quiso ir a la fiesta y decidió regresar para la casa para enterarse del hecho.

Cuando llegó a la casa, efectivamente allí no se encontraban los dos niños que habitualmente estaban sentados alrededor del fogón. Esto le causó al mismo tiempo tristeza y muchos pesares. Sólo se limitó a esperar el regreso de los dos hijos para ver de qué forma llegaban, si en forma de niños o como los hombres que ella había visto varias veces.

Se sentó a pensar. Allí, pensando miles de cosas y cantando, comenzó a marcar el suelo, rayándolo con los dedos de la mano y los pies, de diversas formas que le venían a su mente.

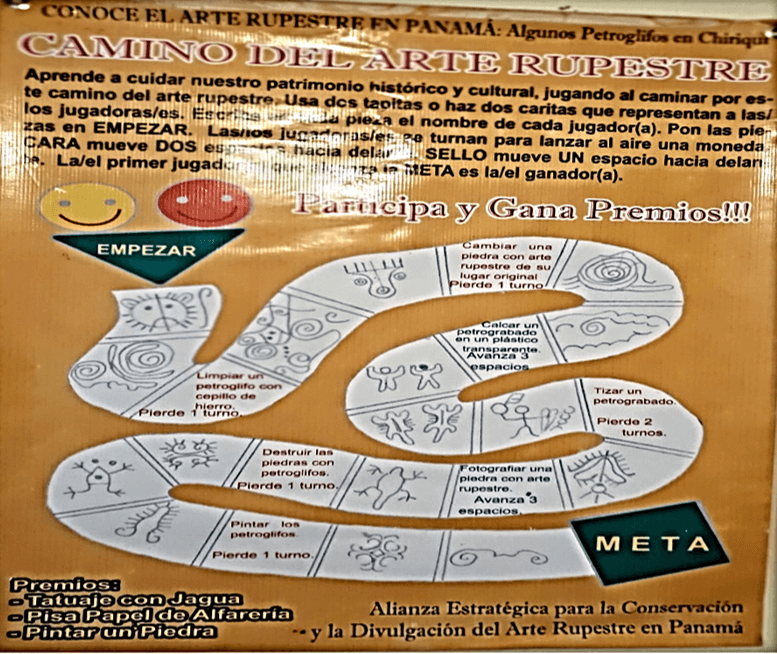

Estas son las señales y marcas que se encuentran grabadas en piedras de diversos lugares de la tierra. Estos grabados son las huellas de los dedos de los pies y manos de Evia y, desde luego, su inspiración.

Petroglifo en toma de agua del acueducto de Boquete, Chiriquí, República. de Panamá | Petroglyph in the water intake of the Boquete aqueduct, Chiriquí, Republic of Panama.

Petroglifo en el patio de la escuela en San Carlos, Coclé, rescatado por una profesora de ciencias y sus alumnos luego de que fuera arrojado a una zanja cuando se hizo la carretera en Copé de San Carlos | Petroglyph in the yard of the school in San Carlos, Coclé, rescued by a profesor of science and her students after it was thrown into a ditch when the road in Copé of San Carlos was made.

Parece que desde ese momento ella no se dedicó a hacer otra cosa más que a esa cosa, hasta que llegaron sus dos hijos. Ellos llegaron, ya no en la forma de niños desnudos y mugrientos quienes se alojaban alrededor del fogón y su refugio para dormir eran las cenizas, sino como hombres de extraordinaria contextura física y de impecables vestidos de color oro y plata, respectivamente, tal como ella logró verlos en tres ocasiones en las fiestas donde fue en vano su esfuerzo por conquistarlos como admiradores o bien como esposos. De esa forma quedó despejada la duda para ella. Ella ni siquiera demostró su angustia y tristeza a los hijos cuando éstos llegaron. Tampoco los hijos le dirigieron la palabra a ella. Tanto la mamá como los hijos sólo se limitaron a observarse mutuamente, como dando a entender que no había sucedido algo que lamentar.

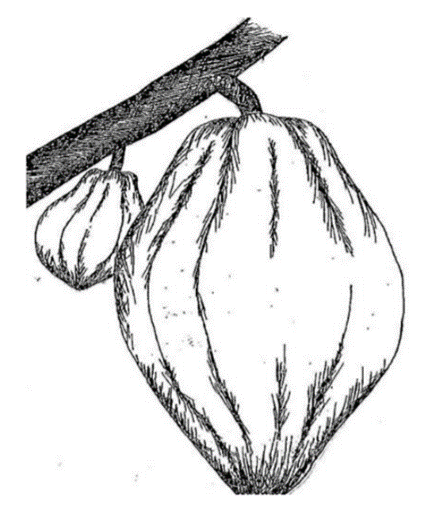

La mamá observaba con atención los movimientos de sus hijos. Los dos simultáneamente dijeron: “Vamos a hacer bebidas de cacao: blanco y colorado” (1).

(1) Cacaos: Se mezclan diferentes tipos de cacaos ya molidos. Se ponen a cocinar hasta cierto tiempo, quedando bastante espeso. Para tomar no se hace bebida de chocolate en gran cantidad, como normalmente se hace; sino, que se calienta agua aparte. Luego esta agua es distribuida en vasijas pequeñas donde estos cacaos preparados se sacan con un mecedor una cantidad pequeña y se mezcla con agua para luego tomar.

Se pusieron de acuerdo quien iba a preparar las bebidas tanto de cacao rojo como del blanco. Uno preparó del cacao blanco y otro del cacao rojo. No quedando del todo conformes, se preguntaron qué otro tipo de bebida iban a preparar, y se dijeron que iba a ser concentrado de cacao y aceite.

Luego ellos se pusieron de acuerdo para tomar las bebidas. Pero antes de tomarlas, se dijeron que tenían que bañarse primero para luego beber y se fueron a bañar al río; le advirtieron el peligro a su mamá, que no se acercara para nada a ver esa cosa que ellos habían dejado en la paila tapada, que no se atreviera a asomar a ver.

Pero la madre hizo caso omiso de la advertencia, argumentando que los dos eran sus hijos y que ella tenía plena autoridad sobre los dos y que como su madre tenía derecho de ver y saber lo que hacían sus hijos. Para ella quien había criado a sus dos hijos desde muy pequeños, no tenían que prohibirle nada a ella ni esconder algo como secreto en su presencia. Ella se asomó y quitó la tapa a las dos pailas. Lo que ella vio fueron dos niños: una niña (cacao rojo) y un niño (cacao blanco). Ambos tenían ensartados en sus ombligos pedazos de palos como si estuvieran asados a crudo. En las pailas esos dos niños estaban como hirviendo en aceite caliente y que salpicaba de modo constante y violento. Al ella asomar la cara, inmediatamente le salpicó la cara una gota caliente cayéndole en los ojos. Inmediatamente le quedaron quemados sus ojos y ciegos para siempre. Ella se revolcó en el suelo con inmenso dolor.

Para sorpresa de los hijos, cuando llegaron encontraron a su madre revolcándose en el suelo. Con disgusto uno de ellos dijo: “¡No es posible, yo le hice la advertencia!”. Ya no habiendo otra alternativa, bebieron los supuestos cacaos que había en la paila. Parecían con esto haber consumado la desgracia de su mamá.

Ellos tomaron la decisión de expulsar a su madre de la casa. Esta decisión reflejaba el disgusto que les había causado. Para ellos, ella no significaba nada en ese momento. Pero, aun así, parecía haber una división de criterio entre los dos. El hijo de vestido de oro parecía más encolerizado y proponía la inmediata ejecución de su mamá. Pero el de vestido de plata todavía parecía tener compasión de su mamá y se abstenía a tomar la decisión de su hermano y se rehusaba a aceptar la condición.

Ya de tanta consulta entre los dos, les pareció la decisión más adecuada, botar de la casa a su madre, lejos, donde jamás volviera a regresar a la casa y que la naturaleza se encargara de ultimar su vida. Ellos la botaron por el lado del oriente. Cuando menos la esperaban, ella regresó luego otra vez a la casa. Haciendo gestos de toda clase y hablando, decía a sus hijos que a ella la habían botado de la casa para que solamente pudiera comer las cáscaras de guanábana, mamey, piña y otras frutas, pero que nunca tendría más la oportunidad de comer las verdaderas frutas.

Cuando la botaron de la casa, la mandaron con un loro que ella tenía. Ese era su único compañero que la iba a acompañar en su destierro.

Los hijos, viendo que no les resultó su plan, entonces volvieron a botarla de la casa, pero esta vez en la dirección del poniente. Tampoco resultó. Ella volvió a llegar en la misma forma que la anterior.

No estando satisfechos, los hijos la botaron por el sur. Tampoco dio resultado ya que ella volvió otra vez. No quedando otra alternativa, la tiraron otra vez del abismo de la tierra. Esta vez no regresó, pero se oía su loro que cantaba.

Artesanía con conchas marinas que representan los cuatro puntos cardinales de un petroglifo en el Parque Arqueológico de Nancito, distrito de Remedios, provincia de Chiriquí, República de Panamá | Handicraft with seashells representing the four cardinal points of a petroglyph in the Archaeological Park of Nancito, district of Remedios, province of Chiriquí, Republic of Panama.

Los hijos fueron a ver y encontraron al loro agarrado en una parte, colgando en el abismo. Lo agarraron y le rompieron la cabeza y luego lo tiraron detrás de su madre para siempre, para que ellos nunca volvieran a ver la cara de ella ni oír su voz.

Cuando ocurría un temblor de tierra, esta señora quería volver a la superficie en la tierra. Su esfuerzo por lograr subir siempre le resultaba en vano y solo lograba mover la tierra. La tierra es como una casa con un jorón arriba, donde para subir hay que hacerlo por una escalera, y para hacerlo movía la casa en su subida. La intención de la señora al subir al jorón era ver si las guanábanas, mameyes, piñas y otras frutas estaban maduras. Estas frutas en nuestros días no son más que los hombres que habitan la tierra.

La señora regresará cuando el sol se vaya poniendo en el poniente, entendiéndose por el atardecer el final del mundo. En otras palabras, esta señora no está muerta, sino que está pagando su pena y al final del mundo ella aparecerá como tal.

Cara del sol y calendario solar y lunar | Sun face and solar and lunar calendar.

Piedra pintada, Caldera, Boquete, Chiriquí, Panamá | Painted stone, Caldera, Boquete, Chiriquí, Panama.

Ya consumado este acto, los hijos se encargaron de la tierra y cada uno se encomendó un trabajo para la eternidad. Estos dos hombres se encomendaron mutuamente la gran misión de cuidar la semilla sobre la tierra (entendiéndose por la semilla de la tierra los hombres que habitamos en ella). El de vestido de oro se encargó de cuidar de día, mientras que el de vestido de plata se encargó de cuidar por la noche. Siendo el de vestido de oro el sol y el de plata la luna, entendiéndose por su misión la de brillar sobre la tierra para la eternidad.

El hombre de vestido de oro era de sangre caliente y, por lo tanto, agresivo y feroz en su luz, tal como es la luz del sol que es caliente. Por este motivo es que fue él quien más se encolerizó y tomó la decisión tajante para con su madre. En pocas palabras, era un hijo malo. Por otro lado, el del vestido de plata era de sangre fría; por lo tanto, paciente, benévolo y agradable su presencia; tal como es la luna, con su luz fría y que no quema ni es caliente como la del sol. Por su benevolencia y buen corazón, todavía, aún después de la desgracia, quería a su desafortunada madre. Con lo que ha ganado el nombre de buen hijo, poco agresivo, amable en su trato.

La humanidad ha sufrido a consecuencia de las sequías causadas por el sol. Mientras la luna muy poco ha importado a la humanidad como astro determinante en su quehacer sobre la tierra.

Esos son los dos niños mugrientos que dormían en la ceniza y fue el fogón donde luego surgieron como gigantes para gobernar con su luz al mundo por largo rato.

Nota del Ingeniero Agrónomo Roger Séptimo Jiménez

Entre los significados que le atribuyen a esta leyenda, según su proceder social y moral, se pueden destacar los siguientes:

- Las madres que poco les importa con sus hijos, que abandonan y descuidan sus hijos por dedicarse a otras actividades para satisfacer sus deseos egoístas e individualistas, corren el peligro o la suerte de que sus hijos, cuando están en sus estados adultos, le paguen con la misma moneda.

- Una madre no puede dedicarse a hacer todas las cosas que se le ocurra hacer libremente delante de sus hijos, quienes, a pesar de que sean niños, se percatan con suma facilidad de la actuación de su madre, y les queda para siempre grabado en su mente. En algún momento cuando se rebelen, le sacarán a relucir a su madre lo que ella ha hecho y, por lo tanto, para ellos, como su madre no signifique gran cosa.

- Las mujeres no solamente tienen que desempeñar el papel de ser madres y traer hijos al mundo, sino que esto implica deberes y responsabilidades de dedicar a sus hijos sus vidas y tiempos, de dar buena educación a sus hijos con buenos ejemplos y no dedicarse a la vida fácil y de poco sacrificio en detrimento de sus hijos.

- Los hijos que se rebelan contra su madre por la vida que lleva, pueden definitivamente abandonarla y alejarse para siempre de la presencia de ella o bien hacerle cualquier maldad par deslingarse de ella. • Las madres nunca deben pensar que sus hijos serán niños indefensos todos los tiempos, sino que ellos serán hombres algún día y actuarán de acuerdo con la enseñanza y el modo de vida en que se han desarrollado como personas y tratarán de imitar o bien actuar todo lo contrario según su conveniencia.

- En el caso particular de la leyenda, las madres no pueden tener la vida de marido y mujer con sus hijos. Estos son actos que resultan vergonzosos y despreciables en la sociedad y, por lo tanto, inconcebibles. Resulta, entonces, que cualquier acción de esta naturaleza que se desarrolle en la sociedad, no es permitida de acuerdo con el criterio social y moral, y se condena como inmoral.

- Puede interpretarse como la ceguera de una madre hacia sus hijos y que, por la vida que lleva, no logra percatarse de la misma. Como en la leyenda, puede resultar la equivocación de la madre de muchas formas; pero, como se dice que los errores son incurables, no vale lamentarse independientemente de que se lleguen a consumir o no los hechos.

Foreword

FOREWORD

To facilitate reading in Ngäbere, we have adapted, with some modifications, the system in the short Ngäbere-Spanish dictionary Kukwe Ngäbere by Melquiades Arosemena and Luciano Javilla, published in 1979 by the Directorate of Historical Heritage of the National Institute of Culture (INAC), now the Ministry of Culture, and the Summer Institute of Linguistics.

It should also be clarified that this story comes from narrators residing in the village of Potrero de Caña, formerly the Tole district of the Chiriquí province, now the Müna district of the Ngäbe Buglé region, from which the Agronomist Roger Séptimo, the compiler and writer is a native. Consequently, the phonology corresponds to the dialectal or regional variation "Guaymí del Interior" (Pacific slope) which differs from the "Guaymí de la Costa" (Caribbean slope of the province of Bocas del Toro and the now district of Kusapin in the Comarca Ngäbe Buglé) in the Guaymí Grammar of Ephraim S. Alphonse Reid, published in 1980 by Fe y Alegría. This variant corresponds to what Arosemena and Javilla call "Chiriquí" and which contrasts with the Caribbean variants of Bocas del Toro and the coast of Bocas.

This ethnohistory was published in 1986 in Kugü Kira Nie Ngäbere / Sucesos Antiguos Dichos en Guaymí (Ethnohistory Guaymí), by the Panamanian Association of Anthropology, with the PN-079 Agreement of the Inter-American Foundation (FIA) managed by Dr. Mac Chapin, Anthropologist, who encouraged us to follow the example he had set by compiling Pab-Igala: Histories of the Kuna Tradition, published in 1970 by the Center for Anthropological Research of the University of Panama, under the direction of Dr. Reina Torres de Araúz.

This book represented the work of the Agricultural Engineer Roger Séptimo, when he was a student in his second year at the Center for Agricultural Teaching and Research in Chiriquí (CEIACHI), Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, University of Panama (FCAUP), not only writing in Ngäbere the stories that he had heard from his family members in his community, but also his effort to translate them into Spanish as a bilingual person that he is, like other indigenous people in Panama, who are striving to receive a formal education.

The ethnohistories were compiled, recorded on cassettes and written by the Agronomist Roger Séptimo in 1983 and 1984.

As Professor-Researcher of Anthropology and Rural Sociology at the CEIACHI of the FCAUP, Luz Graciela Joly Adames, Anthropologist, Ph.D., encouraged Roger, as one of her students, to write the stories, convince him and show him that she would not exploit or abuse his work, but that he would get credit. Consequently, the anthropologist limited herself only to making some corrections of form and style in the Spanish translations without altering their content.

We encourage students from the seven indigenous peoples in the Republic of Panama, and teachers in public and private schools, colleges and universities in Panama, to write in their own languages and translate the ethnohistories and songs they hear in their families and communities into Spanish, as part of their informal education.

We also encourage readers of these ethnohistories in Ngäbere, Spanish and English, to draw the scenes that they liked the most, as they did in 2002, students in an Education and Society course, directed by Dr. Joly, at the Faculty of Education, Autonomous University of Chiriquí.

Article 13 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, approved by the General Assembly, in its 107th plenary session on September 13, 2007:

- Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, promote and pass on to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to name and maintain their communities, places and people.

- The States shall adopt effective measures to ensure the protection of this right and also to ensure that indigenous peoples can understand and make themselves understood in political, legal and administrative actions, providing for this, when necessary, interpretation services or other appropriate means.

THE SUN AND THE MOON

It is said that there was a lady named Evia, who lived only with two very small sons, who nobody knew who was their father. But the truth is that there were two boys living with the lady. The two boys lived in unhealthy conditions, all dirty; their only place was the fireplace of the house, around which they were always sitting or lying on the ashes. Very few times did they go elsewhere.

Their mother liked to be in party after party because she was a notable singer. In one of these parties, she met two men. One was dressed in gold and with a gold cane in one hand, while the other one was dressed in silver (white) and with a silver cane. The lady saw these two so attractive that she dedicated to adorning herself with all kinds of necklaces and dress herself with the best possible way to call the attention of these two men.

She dedicated to sing in front of the two and then would pass in front of the two and step on their feet to demonstrate that she liked those men. Not being satisfied with this demonstration, she decided to make gestures and mimics in front of them to call more their attention. But none of these demonstrations seemed to have any importance for these men. The only thing they would do was to move their feet and change place with the minimum interest in her.

But there was someone who did know the whereabouts of those men. In fact, they were the sons of this lady. That person warned the lady not to do such disagreeable spectacles as those men were her two sons.

She answered saying that they were not her sons, that the poor boys had stayed dirty, lying on the ashes of the fireplace in the house when she had left for the party, and that never could they be compared to the figures of those men so notable.

The two men at no moment paid attention to her and continued participating in the party without any novelty. She insisted on following them until the end of the party. Not being able to get her intention, she returned to her house. For her surprise, there were the two boys sitting by the fireplace. This gave her more confidence in believing that those two men whom she had seen in the party were not her sons. This meant that she did not know her sons nor the power that her sons had to become the men whom she had met.

Then there came the opportunity to go to another party and the coincidence that she met the same men. Without wasting any time, she renewed the same demonstrations to call again the attention of her desired men. She hoped that at least one of the two could be interested in her. But, as the first time, she did not get anything from those two men.

As the previous time, there was one person who called her attention, to please not commit such an immoral and painful act. But she did not believe anyone, as the first time when she got to the house there were the two boys in the house by the fireplace.

In spite of all her endeavors, neither this time did she achieve to interest the two men in her person. They always tried to evade her presence because of the things that she did to them.

When the party ended, she returned to the house, finding the two boys by the fireplace the same way that she had found them before. This caused her confusion and could not believe that those were her sons.

She went to another party and the same inexplicable phenomenon repeated again, for her luck. The thing that most worried her was that, although she liked those men, there was always someone who mortified her conscience telling her that those were her sons.

This time, more confused than ever, she returned to her house and, for her luck, the two boys were in the house.

When there came the time to go to another party, for the fourth time she found those two men. To get rid of any doubt, she left for the party; but, by the middle of the road, she hid on one side of the road to wait if those men were her sons. Then she would see if they came out behind her and in this way, she could see them go by. For her surprise, she saw the same men pass behind her to go to the party. Motivated by this surprise, she did not go to the party and decided to return to the house to find out the fact.

When she got to the house, the two boys were not where they usually sat by the fireplace. This caused her at the same time sadness and much grieve. She only limited herself to wait for the return of her two sons to see in which form they would arrive, if as boys or as the men she had seen several times.

She sat thinking. There, thinking thousands of things and singing, she began to mark the ground, scratching it with the fingers of her hands and feet, in diverse forms that came to her mind.

These are the signs and marks that are found engraved on rocks in different places of the earth. Those engravings are the fingerprints of her hands and feet and, of course, her inspiration.

Petroglifo en toma de agua del acueducto de Boquete, Chiriquí, República. de Panamá | Petroglyph in the water intake of the Boquete aqueduct, Chiriquí, Republic of Panama.

Petroglifo en el patio de la escuela en San Carlos, Coclé, rescatado por una profesora de ciencias y sus alumnos luego de que fuera arrojado a una zanja cuando se hizo la carretera en Copé de San Carlos | Petroglyph in the yard of the school in San Carlos, Coclé, rescued by a profesor of science and her students after it was thrown into a ditch when the road in Copé of San Carlos was made.

It seems that from that moment on, she dedicated herself to do no other thing but only that thing, until her two sons returned. They came, not in the form of naked and dirty boys whose refuge to sleep was the ashes by the fireplace, but as the men of extraordinary physical appearance and impeccably dressed in gold and silver, just as she had seen them in three occasions in the parties when her efforts were in vain to conquer them as admirers or as husbands. In this way her doubt was dismissed. She did not even demonstrate to her sons’ anguish or sadness when they arrived. Neither did the sons speak to her. Both the mother and the sons only limited themselves to observe each other, as if meaning that nothing had occurred to be sorry about.

The mother observed attentively the movements of her sons. The two simultaneously said: “Let’s make beverages of cocoa: white and red cocoa” (1).

(1) Cocoas: Different types of ground cocoas are mixed and they are cooked for a certain time until thick. To drink, it is not as a chocolate beverage as is usually done in great quantity, but water is heated aside. Then, this water is distributed in small vases, in which the prepared cocoas are taken with a stirring stick in a small quantity and mixed with the water to drink.

They agreed who was going to prepare both the red and white cocoa drinks. One prepared from white cocoa and another from red cocoa. Not being entirely satisfied, they wondered what other type of drink they were going to prepare, and they told themselves that it was going to be cocoa concentrate and oil.

Then they agreed to have the drinks. But before taking them, they told themselves that they had to bathe first and then drink and they went to bathe in the river; They warned her mother of danger, that she should not come near to see that thing that they had left in the covered pot, that she did not dare to appear to see.

But the mother did not pay attention to the warning, arguing that the two were her sons and she had full authority over the two and, as their mother, she had the right to see and know what her sons were doing. For her, who had raised her two sons since very small, they did not have to forbid her anything nor hide anything as a secret from her presence. She uncapped the two pots to see. What she saw were two children: a girl (red cocoa) and a boy (white cocoa). Both had sticks in their belly buttons as if being roasted alive. In the pots those two children were boiling in hot oil that splattered constantly and violently. As she put her face to see, immediately a drop of hot oil fell on her eyes. Immediately both eyes were burned and she became blind forever. She rolled on the ground with immense pain.

For their surprise, when her sons arrived, they found their mother rolling on the ground. With disgust, one of them said: “It is not possible, I warned her!” There being no other alternative, they drank the supposed cocoas that were in the pots. It seemed that in doing this they were consummating the disgrace of their mother.

They decided to throw their mother away from the house. This decision reflected the disgust that she had caused them. For them, she did not mean anything at that moment. But even so, there seemed to be a division of criteria between the two. The son dressed in gold seemed to be more angry and he proposed the immediate execution of his mother. But the one dressed in silver seemed to still feel compassion for his mother and he abstained to take the decision of his brother and refused to accept that condition.

After so much consultation between the two, it seemed the most adequate decision to throw their mother far away, from where she could not return to the house and let nature take care of her life. They threw her by the east. When they least expected her, she returned again to the house. Making all kinds of gestures and talking, she said to her sons that they had thrown her away from the house so that she could only eat the skins of the soursop, mamey, pineapple, and other fruits, but never have the opportunity to eat the real fruits.

When they threw her out of the house, they sent her with her parrot. That was the only companion she would have in her exile.

The sons, seeing that their plan did not work out, then they again threw her out of the house, but this time to the west. Neither did it work out. She returned in the same way as before.

Not being satisfied, the sons threw her to the south. Neither did it work out, as she returned again. Not being any other alternative, they threw her away again to the abyss of the earth. This time she did not return, but they could hear her parrot singing.

Artesanía con conchas marinas que representan los cuatro puntos cardinales de un petroglifo en el Parque Arqueológico de Nancito, distrito de Remedios, provincia de Chiriquí, República de Panamá | Handicraft with seashells representing the four cardinal points of a petroglyph in the Archaeological Park of Nancito, district of Remedios, province of Chiriquí, Republic of Panama.

The sons went to see and found the parrot hanging by a part of the abyss. They took it and broke its head and then threw it behind their mother forever, so that they would never see her face nor hear her voice.

When there was an earthquake, it was that this lady wanted to return to the surface of the earth. Her effort to climb up always resulted in vain and she only would shake the earth. The earth is like a house with a loft upstairs, where to climb up there it is with a ladder, and in doing so the whole house would move in her climbing. The intention of the lady to climb to the loft was to see if the soursops, mameys, pineapples and other fruits were ripe. These fruits in our days are the people who inhabit the earth.

The lady will return when the sun is setting on the west, meaning by the sunset the end of the world. In other words, this lady is not dead, but is paying her pain and at the end of the world she will appear as such.

Cara del sol y calendario solar y lunar | Sun face and solar and lunar calendar.

Piedra pintada, Caldera, Boquete, Chiriquí, Panamá | Painted stone, Caldera, Boquete, Chiriquí, Panama.

Having consummated this act, the sons took care of the earth and each one took charge of a job for all eternity. These two men mutually agreed to do the great mission of caring for the seeds on earth (meaning the seeds on earth the people who inhabit the earth). The one dressed in gold took charge of caring during the daytime, while the one dressed in silver took charge of caring at night. Becoming the sun the one dressed in gold and the moon the one dressed in silver, being their mission to shine over the earth for all eternity.

The man dressed in gold was of hot blood and, therefore, was aggressive and fierce as the hot light of the sun. That is why he was so enraged that he took such an outrageous decision with his mother. In other words, he was a bad son. On the other hand, the one dressed in silver was of cold blood, therefore, patient, kind, and of agreeable presence, such as the moon, with its cool light that doesn´t burn nor is hot as the sun. For his kindness and good heart, even after the disgrace of his mother, he loved his unfortunate mother. That´s why he has earned the fame of being a good son, not aggressive, kind in his ways.

Humanity has suffered as a consequence of draughts caused by the sun. On the other hand, humanity has paid little importance to the moon as a determinant luminous body of the heavens in caring for the earth.

Those were the two dirty boys who slept on the ashes and it was the fireplace from where they rose as giants to govern the world with their light for a long time.

Note by Agricultural Engineer Roger Séptimo Jiménez

Among the meanings that are given to this legend, according to social and moral behavior, the following can be signaled out:

- Mothers who do not give importance to their children, who abandon and are careless with their children, to dedicate themselves to other activities to satisfy their selfish and individualistic desires, take the risk or luck that their children, when they are adults, will pay them back with the same coin.

- A mother cannot dedicate herself to do all the things that she freely wants to do in front of her children, who, even though they are children, will easily be aware of their mother´s behavior, and it will be engraved in their minds forever. At some time, when the rebel, they will let their mother know what she had done and, therefore, for them, their mother does not mean much.

- Women not only have to do the role of being mothers and bring children into the world, but this implies duties and responsibilities to dedicate their lives and time to their children, to give a good education to their children with good examples and not dedicate themselves to an easy life of little sacrifice in detriment of the wellbeing of their children.

- Children who rebel against their mother for the life that she has, may definitely abandon her and exile themselves from her presence forever, or do an evilness to her to get rid of her.

- Mothers cannot think that their children will be defenseless all the time, but the children will grow up someday and will act according to the teachings and way of life in which they have grown as persons and will try to imitate or act all the contrary according to their convenience.

- In the particular case of this legend, mothers cannot have the life of husband and wife with their sons. These acts are shameful and contemptible in society and, therefore, unconceivable. It means that any action of this nature that occurs in the society, is not allowed according to social and moral criteria, and is condemned as immoral.

- It can be interpreted as blindness of a mother toward her sons and that, because of the life that she lives, is not aware of it. As in this legend, it can be a mistake of the mother in various ways; but, as it is said that errors are uncurable, it is not worth lamenting independently if the act is done or not.

Nieta abogo Kira, meri nomlen nünen iti abogo kädian nomlen Evia, nomlen nünen ngöbo kia nibube ben kaibe nguarabe, ngöbo ne abogo rün ñó gare ñagare tari.

Ngöbo nibu aibe ben nomlen nünen käre. Ngäbägre nibu ne nomlen nünen ennen, nünen nguarabe, nünen bütiere amlen dobrore. Nomlen nüen käre ñüguäbata abogo bata nomlentre kibien bäre temen. Ne abogo tägälinte ñüguäbata erenguanen abogo kitalinte ngübrünte temen. Ne abogo kontdi nain ñagare krägrä, nebe ñagare niguen ju madate temen. Akua meye abogo käre nebe döbata niguen kä ngrabre temen, neabogo kagä krií aicete nebe kare niguen döte kä madabiti temen. Ne abogo nain käre Krörö döbata niguen kä ngrabre temen. Ne krere nomlen döbata kontdi ni gualin nibu ie döbata, ni toen ñagare krere kualin ie döbata. Iti nguä orore kä nomlen mogän orore nguen kisite arato, amlen iti abogo nguä ngüianen kä nomlen mogän ngüianen nguen arato kisete. Ni ne abogo namalin toen kuin mada Evia ye, abogo nigalin ja kälennen mada bentre, ñara nigalin ja dätere jondron bätägä nguarebe biti arato, ne abogo rabadre toen kuin arato nineye abogo gäre namanlin noenen.

Namalin ja nguä guite bätägä nguarabe bata namanlin ja dätere arato, ne abogo ngäbe nibu ne meden ye rebadre toen kuin abogo kärere namanlin noenen. Biti namanlin kare mada bäre temen, ne abogo jata bäre temen jatabe däte ngötobiti, ne abogo ja kalenen bentre ne abogo ngäbe nibu ne namanlin toen kuin ie, abogo kä namanlin däte ngötobiti abogo migue gare kröro ietre. Namanlintre toen kuin jogrä ie abogo namanlin bä migue oguäte. Ne abogo tebai namanlin ñagare ngäbe negüe, nebata abogo ñara namanlin ja kuite bätägä be nguarabe oguäbiti mada, ne abogo meden ye rebei toen kuin abogo gare namanlin kugüe noenen Kröro. Akua ngäbe nibu ne abogo kä namanlin tebaire ñákara, abogo nomlen jämen jiriäbe, nin namanlin ñara tebaire.

Ne abogo kare bata ja migue bätäga be nguarabe jatabe däte ngäbe ne ngötobiti, abogo känamanlin ngöto dengä jiriäbe mentonguälen, ne biti nin tebai kuetre, ne abogo ñara abogo namanlin kugüe noenen kröro mada batatre. Akua ni mada abogo ie ni ne gare kuin, abogo kägüe ñägäbare mada ñara ye, ñan kugüe noemlan kämen ie ni kuatií oguäbiti, ñan jádagamlan ie ngöbobta.

Ne amlen ni ne abogo ñara ngöbo, abogo ñara ye ñan namanlin nügueta gare, abogo nomlen kugüe noenen krörö bata. Ngöbo kue bata nomlen kugüe noenen nie namanlin ie. Akua ñara abogo kägüe ñan mialin era, ñara namanlin niere abogo, ni ne abogo ñan ñara ngöbo amatibe abogo nie namanlin ie, namalin niere jiriäbe. Ngöbo kía bobre manlin guí ie ngübrünte, amlen ñara nigalin döbata ne abogo ñan abogo nomlen dobata niebare kue. Amlen ñan ngöbo ni ne kreretre amatibe, abogo nie manalin ie, namanlin niere jabata.

Ngöbo abogo kía amlen bütiere dobrore namanlin guí ngübrünte ie abogo bata töi namanlin kä namanlin ja kuete. Ne amlen ngäbe nibu, ne abogo nomlen jämen döbata abogo namanlin ñara tebaire ñágare, amlen namanlin kä miguegä jiriäbe bata. Ne akua ñara abogo namanlin nain kisere jiöbiti, te dö nigalin ta. Töbiabare nguarabe kue ngäbe nibu ne ye. Tö namanlin kugüe noenen krere ñan namanlin bare ie amlen dö nigalin ta, nebiti jatalinta ja griete.

Jatalinta guägare amlen ngöbo Kía nibu tägälinte ñüguäbata bata nügalinta. Ne bata bäri töi namanlin mada abogo ni toalin kue dötde ne abogo ñan ñara ngöbo, amlen ni genenan abogo bata ñägä namanlin nguarabe ie namanlin nütre mada. Ne amlen ñara abogo ie ngöbo töi ñó gare ñácare arato aicete namalin töbigue kröro, ne amlen ngöbo abogo töi krigri, nigüite ni toalin kue ne krere abogo gare ñagare ie. Amlen ñara nomlen kugüe noenen kaibe arato aicete niebare ñagare kue ngöbo ye.

Nebiti dö mada noembare bata nigalinta bugüta, namanlin dötde amlen ni toalin kue dötde kälin kue ne arabe kuentre ie döbata buguta. Nin kä mialin niguen raire ta kue amlen nigalinta be ja kälennenta bentre, ne ñara abogo tö namlin rabai ni nebe, itibe, meden ere ñaragüe kai ngabiti abogo bata toi namalin kä namanlinta já kälennen bentre. Ne nguan-re abogo ñara tö namanlin itibe ie, meden ere abogo namanlin guibiare jai, meden ye rebei toen kuin abogo tari namanlin nain jiöbiti. Akua nögalingä kälin bata krere nogalingäta buguta bata, nin tebaibare jire ngäbe negüe, ñaragüe ja nigalin nguarabe.

Ñägäbare ie dötde kälin ne krere ñäga bareta buguta ie, ñan kugüe noemlan kämen ie, ñan jádagamlan ie ngöbobata ni kuatií dotde oguäbiti ie. Akua ñara abogo kägüe nin mialin tatde, nin mialin era kälin kue ne krere bareta buguta kue. Ne nguan-re ñägä namanlin ie, ñara abogo nin namanlin tebaire, ne ñó bata amlen ñägäbare krörö kälin ie biti ñara nigalinta güägäre amlen ngöbo nomlen ñüguäbata güí bata namanlita aicete ne nguan-ne ñagäbare nguarabe ie. Ja mialin bätäga be nguarabe kue ja kälombare kisetde kue ngäbe nebe, akua kälin krere ñan tebaibare jire ni nibu negüe, ni ne abogo namanlin kä miegä jiriäbe kälin ñan tö namanlin ja toai nguarere ñarabe, abogo namanlin nguitie jiriäbe bata. Dö nigalin ta buguta, amlen ñara jatalinta ja griete, kälin krere buguta ngöbo kía nibu kuekebe tägälinte ñüguäbata biti jatalinta guägäre. Ne amlen namanlin tebaidre krägä akua ñan namanlin nebe era krägä, ni ne abogo ñan ñara ngöbo abogo bata toi namanlin, ngöbo käre guí ie kitdetda guägäre amatibe abogo keta nomlen ni toa nomlen kue dötde abogo bata, ne bata abogo ñan namanlin nebe era kräga.

Nebiti kirara nigalinta buguta döbata kugüe nögalingäta kälin krere buguta bata, ne amlen bämä gärera, amlen ñan namanlin noenen krägä, dre noen kue ñan namanlin nügue gare ie.

Ne ñó amatibe ni namanlin toen kuin ie abogo ni mada abogo namanlin ñägue bata ñara ye, niere ie abogo ni ne, ñan ni genenan amlen ñara ngöbo nibu abogo, ne abogo ñan namanlin nebe debe krägä amlen ñan namanlin nügue gare ie.

Dö nigalintda ta buguta amlen jatalinta, amlen namalin tebaidre ñara grä mada biti jatalinta guägrä amlen ngöbo kía nibu kuekebe güi bata nügalinta, nomlen bata nügalinta kälin krere jämen güi bata nügalinta buguta. Nebiti dö mada noembareta buguta ne bäboga-gärera, ne amlen gotäita buguta ni nebe buguta dö netde namanlin roen ñaraye. Akua nigalinta dö bata amlen tö namanlin kügüe ñó gaí mada, ne abogo ñó metre abogo tö namanlin kugüe ño gaí mada, ne abogo ñó metre abogo tö namanlin gai mada, abogo namanlin jingrabre konti nigalin könse ja rüguente, abogo ni ne ñara ngöbo bogonlen na amlen naintre ñara jiöbite döbata abogo toi jite kue abogo bata töi namanlin, ne amlen batibe mie era kue namanlin nutre mada. Ne ñöbata amlen ni ne abogo ñara ngöbo niebarera bärebäre ie abogo tö namanlin gai metre mada.

Petroglifo en toma de agua del acueducto de Boquete, Chiriquí, República. de Panamá | Petroglyph in the water intake of the Boquete aqueduct, Chiriquí, Republic of Panama.

Petroglifo en el patio de la escuela en San Carlos, Coclé, rescatado por una profesora de ciencias y sus alumnos luego de que fuera arrojado a una zanja cuando se hizo la carretera en Copé de San Carlos | Petroglyph in the yard of the school in San Carlos, Coclé, rescued by a profesor of science and her students after it was thrown into a ditch when the road in Copé of San Carlos was made.

Ne krere nomlen ja rügalinte könse amlen ni toa namlen nibu dötde kue ne krere nigalin bongonlen ñara jiöbite döbata, nigalin jingrabare ñara bäre ta. Nigalin ta ogüabiti amlen ñara jadalinda jite amlen ñan nigalin döbata mada, amlen jadalinda jiriäbe guä, ne abogo ño tö namanlin gai metre kä jadalinda, gainta guä.

Jatdlintda guägäre amlen ngöbo kía nibu ñágare bogonlen ñüguäbata, amlen ñagare güí arato. Amlen namanlin tebaire krí mada krägra, namanlin tö bigue krií mada nebata. Abogo namanlin ngöbo nibu guibiareta mada guägare, jateita ño guägäre abogo namanlin guibiare mada, jateita ni toa nomlen döte kue ne krere ya ó jateita guägäre kia nomlen nümen ben güí ne krere ya, ñó abogó namanlin guibiareta guägäre mada.

Namanlin tägälinte abogo tö bigue kuati mada, abogo kare sete, ne abogo kä tärä tdigue ja bäre kuariguari, kisibite, ngöto biti niguen temen, kä tärä tdigue bötögä nguarabe sete, tö bigue ñó sete abogo bata kä tärä tdigue arato niguen temen. Ne abogo tö tä matare niguen kä ngrabre temen, niguen jäbata temen, ngöto, kise tä niguen jäbata kä ngrabre temen. Tö bigabare ñó kue abogo tigalin ngöto biti, kisebiti kue jäbata niguen kä jogrä biti temen ne abogo tä kälimen matare nieta. Ne amlen ñara namanlinta güí amlen ñan jondron mada noembare kue amlen namanlin tägälinte abogo tö bigue, kare bata kä tära tdigue ja bare kuäriguäri temen abogo ngöbo giibiareta guägäre. Ne abogo nomlen kröro amlen ngöbo nibu nigalinta guägäre, ne amlen ñan ngöbagre kia dobrore, büitiere, kibien ngübrente güí, ne abogo ñacare amlen ni krigri nibu nguä toare erebe nigalinta guägäre, iti nguä orore amlen iti abogo nguä ngüianen, ñara nomlen toen döte krere nigalin bongonlen guagare ie.

Ni bentre ñara nomlen ja kälenen kisite, ni namanlin toen kuin ie ben tö namanlin rabaí, abogo ne nguanne nigalin nibu ja jiöbiti guägäre ie. Ne amlen batibe kä trä guitialinga ñara oguäte, amlen nanamlin era krägä arato, ne amlen ñäga nomlen döte ie, abogo era bogonlen galin kue, ne ñan ñägä nomlen nguarabe ie, nebra bogonlen.

Kugüe ñó galin-ra kue, akua ngöbo namanlinta ñaragüe tebaitdare ñagare, ñan namalin ja gaire ngöbo gäbite amlen namanlin ja mie, jämen jiriäbe ngöbo gäbiti, namanlinta güí amlen. Krere bare ngöbo nibu kägüe arato, nigalinta jämentre guägäre, me güe ñägäbare ñagare ietre amlen ñägäbaretre ñagare arato kue meye ja mialintre ñärare jiriäbe kuetre biti namanlintre kueguebe, kugüe nögainga ñagare sete krere namanlinta jämentre güí ja guibiaretre jiriaäbe. Ne akua meg abogo namanlin ngöbo guibiaretari mogre mada. Ngöbo nibu kägüe ñagäbare jai “Ari kä tain, nguen sribiere ñare jai” niebaretre kue. Nebiti niregüe kä tain, kä nguen sribedi abogo niebaretre kue jai, ne iti kägüe kä tain sribedi amlen iti kägüe kä nguen sribedi niebare Kuetre jai.

Ne krere iti kägüe kä tain sribebare amlen iti kägüe kä nguen sribebare. Kä namnlin bare ietre amlen nguanlintari kuetre jai kä sribedi ñó ñare niebare kuetre jai, amlen kä köitiguei ñare niebaretre kue jai.

Nebiti kä namanlin-ra ñare be, amlen niebaretre kue jai jubadi kälin biti nigüe ñadi niebare kue, biti nigalintre yägue jüben mötda, amlen kä ügüente jue migalin kuetre biti, nigalintre jibiti amlen ñögäbare kue meyeye, “Jondron bigue nebe kaibe ñan tö nguan toei konti, ñan toate ngöbögra, jondron bigue neben kaibe”, niebare kuetre biti nigalin.

Akua meg abogo kägüe ñan mialin tötde, amlen niebare jiriabe kue, ngöbo nguibia bare kía kue, ne amatibe guiere noen nomlen kuetre abogo ñan namanlin toare ñara gröga niebare kue. Ngöbo guibiabare kía kue aicete abogo jondron noendre ngöbo güe ne abogo ñan dogä tögare ñare be, ne abogo ñan toare té kröga amatibe ngöbogüe dogätägälin ben niebare kue.

Ñan ngöbogüe mätradre ñarabata amlen kue mätradre ngöbo bata ne aicete abogo jondron noemdre kaibe ngöbogüe ne abogo ñan toare blo ñaragrä, niebare kue, tigüe ni guiabare kía ne abogo ñó bren jondron noenta abogo ñan raba toadre tigüe, ne guiere amatibe bren toadre, namanlin niere. Ne biti nigalin üguen nomlen jue mialin ngöbogüe jue dialingä kue nigrabare kue üguente amlen, üguen kubu te ngäbägre ngötrö därebe nomlen nibu, merire iti amlen brare iti, ne amlen kä tain abogo ngäbägre merire amlen kä nguen abogo ngäbägre brare. Ngäbägre nibu üguente abogo krito grialin tuglote ta erebe, jondron kugua kritoba sete krere.

Ne amlen ngäbägre nibu abogo nogregä kootde üguente, bete kuntibe nguinse. Ñara kägüe mialin ñarare nguinse konti kä nguiri nguinse nangualimen guärebata, nigalimen oguäte kägüe ñara oguä kugualinse jogrä kuariguari, konti oguä guetralintebe ie käre gäre. Namanlin kä igote jötrö nguarabe.

Artesanía con conchas marinas que representan los cuatro puntos cardinales de un petroglifo en el Parque Arqueológico de Nancito, distrito de Remedios, provincia de Chiriquí, República de Panamá | Handicraft with seashells representing the four cardinal points of a petroglyph in the Archaeological Park of Nancito, district of Remedios, province of Chiriquí, Republic of Panama.

Konti nigalin betete nguarabe niguen tementda oguä nguetralinte doräibe.

Ngöbo jatalintatre guägäre amlen ñara abogo betetde nguarabe niguen tementda, neben nguarabe jabe bata ngöbo nügalinta. Ngäbriänga oguä namanlin bata, amlen iti namanlin robom kägüe ñägäbare ie, “Ñagare bäre, tigüe ñärira bäre” niebare kue meye. Ne amlen namanlinra bare, ñan krägue namanlinra. Ne biti kä ñälintre kue.

Ne amlen nigalinra nguarabe, Krägätre. Amlen ñan tö namanlinna meyeye aicete namanlin kitadregä kuetre ñan tö namanlin meg toai nünen jabe güi tö namanlin nünentre kaibe güí.

Mätä namanlin bata aicete ñan tö namanlin toai ja nguaregrí, namanlin-ra nguarabe krägätre. Akua ne amlen töi namanlin ñagare ja érebe. Ngöbo nguä orore abogo töir namanlin kuatibe krägä, abogo tö namanlin kiteiga jötrö ja nguaregri, ne bäri motdo namanlin robom megrä. Akua ngöbo nguä ngüiannen abogo namanlin robom megrä akua abogo ie meg nomlen roentdari tare abogo ñan tö namanlin kiteigä jötro, abogo bata namanlin nebeta kueguebe, ne abogo töi ñagare eteba krere aicete abogo kue nomlen toen jagüe, abogo ñan tö namanlin kugüe noenen kämen mebata.

Ne kríídiare te nügalimbiti eteba itiye, ne abogo meg diandregä güi kuetre biti kitaga janandre kä madabiti temen abogo nügalinbiti ietre.

Cara del sol y calendario solar y lunar | Sun face and solar and lunar calendar.

Piedra pintada, Caldera, Boquete, Chiriquí, Panamá | Painted stone, Caldera, Boquete, Chiriquí, Panama.

Ne abogo me kitadiga move kuetre kä mentebitdi abogo konti nin toeita mada kuetre, ne konti nin rügaita güí amlen ne konti jraindre ñó kärera, abogo nin toita ja nguaregri kuetre abogo bata töi namanlintre. Ne biti janamlen meg kitegä kädriri, biti nügalinta güi, meg kitalingära kuetre biti nomlen jämen, amlen batibe me jatalinta jióbiti guägäre, kugüe kuati, ñague bätägabe nguarabe bata ja mie bätägäbe nguarabe bata ja mie bätägäbe nguarabe nainta guägäre buguta. Amlen jatalin ñägue guägäre ngöboye, ngöbogue kitalingä nguarabe abogo sonron, nomon, müa kuata be kuatagä kitalingä jatalin niere guägäre ngöboye, ne abogo jagüe ñan sonron, nomon, müa bogon kuata rirata aicete abogo ja kitalingä kuata be abogo kuatagä namanlin niere mada. Ngöbogüe kitalinga amlen ore nomlen kue kuati ben ngöi kitalinga ne be abogo ben nomlen, nain, ne abogo non mogogä kue ben nügalinta.

Ñan namanlin kitalingä ngäbriangä ya Kadriri abogo ben kitalingäta buguta kuetre, akua ne nguan-re abogo kitalingä kue nidrinin ne abogo ñan namanlin bare arato ietre, meg nügalinta buguta güí, jatalin kälin guägäre ne krere jatalinta buguta guägäre.

Ne amlen kitalingä buguta kuetre, ne amlen kitalingä kuetre nguitära grí.

Akua nügalinta buguta güí. Bäbägä gäre kitalingä kuetre amlen kitalingä mötdari kuetre, akua meg namanlinta güí ietre buguta. Ne amlen ñan tö namanlin-ra meye aicete kiteigä jäglum gäre kuetre abogo töi namanlintre. Ñan namanlin noendre mada krägätre, ben bäringue gäre kitalingä kuetre, ne amlen kitalin kä timon biti kuetre. Ne amlen batibe ñan nügalinta akua ore kue abogo kugüe namanlin roen ngöboye, te nigalin toentre konti, amlen ore nomlen kuekebe namanlinga kä ogobata, bata namanlintre konti ore kalin kuetre biti doguä ötalinte ta kuetre biti kitalin meg jiöbiti kue kä timon biti. Ne amlen nigalin jäglum, ne amlen ñan, kugüe noalinta mada kuetre, amlen ñan toalinta mada kuetre ne amlen nigalin käre gäre bogonlen. Ne amlen nieta abogo Evia tö nomlen nainta kä kuinbiti abogo kä nomlen nebe kä ngrüguete, ne amlen dobo nomlen nebe nogaingä. Ne abogo ja di migue nongrä kuguälen abogo nomlen nebe kä ngrüguete temen, ne abogo ja nigue nguarabe, ñan nürata kä nebiti nieta.

Ne abogo tö tda neve nigren jon teri kuin, abogo tö tda neve nain ku-ngualen abogo tda neve kä ngrüguete temen nie nomlen amlen nie tda matare abogo, ne abogo oguä nebe ñagare jon teri nieta ne abogo tö tda nebe main jon teri abogo sonron, nomon, müa, nenan kure ya o ñó abogo tö tda neve gai, abogo ie tö tda neve nain jon teri kuin.

Müa, sonron, nomon ne abogo ni näire matare abogo, ni nünanga temen abogo nieta. Meri ne abogo rügueita kä nebiti nieta, kä dere amlen rügueita nieta. Ne abogo ñan krütalin amlen tä nire, akua ñara abogo tä ja nguie noen, abogo kä de amlen batibe rügueita kä nebiti. Ngöbo tö nomanlin kitaiga käre gäre krere namanlin bare ietre bogonlen, amlen batibe namanlintre jämen.

Ne biti sribi mialin ja guisete käre gäre kuetre kä nguiabiagä temen mada. Jamialintre kue nüra nguibiaga temen, nüra ne abogo ni nünanga niguen temen ne abogo gäräbere kuetre. Ngüa orore abogo kägüe nüra nguibiai rare niebare kue, amlen ngüa ngüianen abogo kägue nguibiai dibire niebare kue. Ne abogo ngüa orore abogo ñäglon, amlen ngüa ngüianen abogo sö, ne abogo träbiti kä nguibiadi temen kue abogo gäräbare kuetre. Ngüa orore abogo därie guire, abogo bata motdo robom arato, ne aicete abogo ñaglon trä nguire amlen ni kugüe arato. Ne aicete abogo bäri namanlin robom megrä amlen töi namanlin kuatibe megrä, ne amlen ngäbägre robom amlen töi kämen.

Amlen nguä ngüianen abogo därie tibo, abogo bata jämen arato, abogo töi kuin, abogo erere, abogo sö trä tibo, amlen ni kugüe ñagare, amlen nguire ñagare arato. Ne aicete abogo kue meg nomlen tare kue kugüe nögalingä bata biti. Ne abogo ngöbo kuin. Ne aicete abogo ñäglon kä rötega temen amlen nüra kamigata kue, abogo konti mrö nüata krií erenguanen temen, amlen sö abogo kadrie ñagare ne krere abogo biti kä nügue ne. Ngäbägre kía bütiegrä dobrore, kibien ngübrünte temen, abogo meg nomlen miguete kaibe güí abogo nigüitaliln krigrí krüguäte abogo käta träbiti kä nguibiare, ni nguibiare temen kä guí nguen degä abogo biti kä nügue ne, abogo trä jondrin kraere matdare amlen ne krere jétebe arato nie krörö ngabegüe.